This is the text of a talk originally presented at the Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies at the Ohio State University in September, 2019. I presented a shorter version of the paper at Dark Archives: A Conference on the Medieval Unread and Unreadable, at Oxford University in September 2019.

Good afternoon, and thank you everyone for coming today. Thanks especially to the Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies for inviting me, to Chris Highley and Leslie Lockett for organizing, and to Nick Spitulski for making all my travel arrangements.

The advertised topic of today’s talk is Books of Hours as Transformative Works, and I’m excited to be here to talk to you about this work that I’m really only beginning to work on. I’m hoping that we have time in Q&A to have a good discussion, and that I might be able to learn from you.

But first, a bit about me so you know where we’re starting.

I am a librarian and curator at the Schoenberg Institute for Manuscript Studies (SIMS), which is a research and development group in the Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts at the University of Pennsylvania. I’ve been at Penn, at SIMS, for six years, since SIMS was founded in 2013. The work we do at SIMS is focused broadly on medieval manuscripts and on digital medieval manuscripts – we have databases we host, we work with the physical collections in the library, we collaborate on a number of projects hosted at other institutions. Anything manuscript related, we’re interested in.

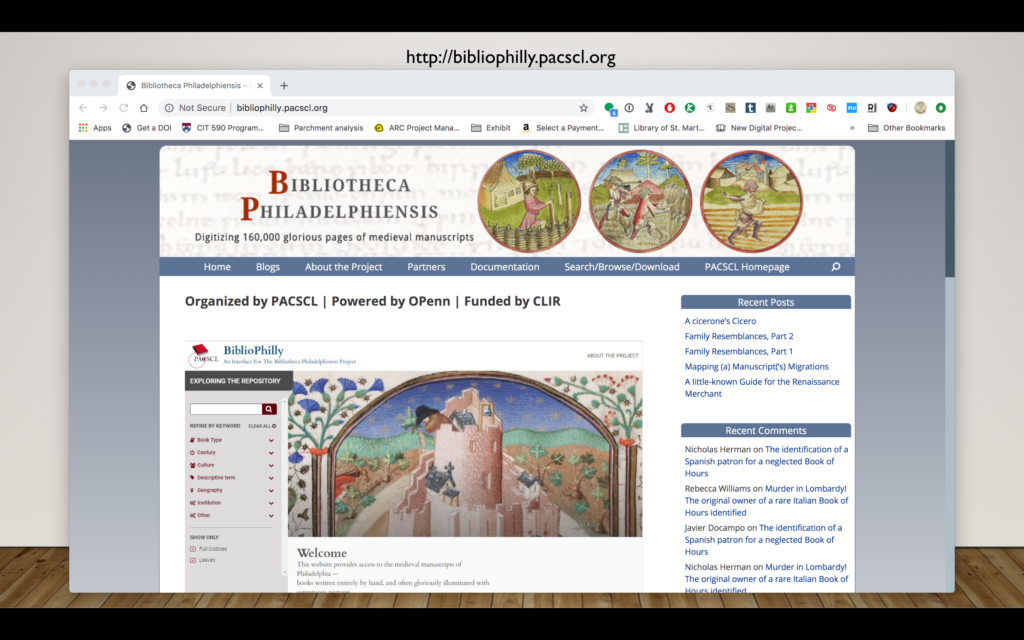

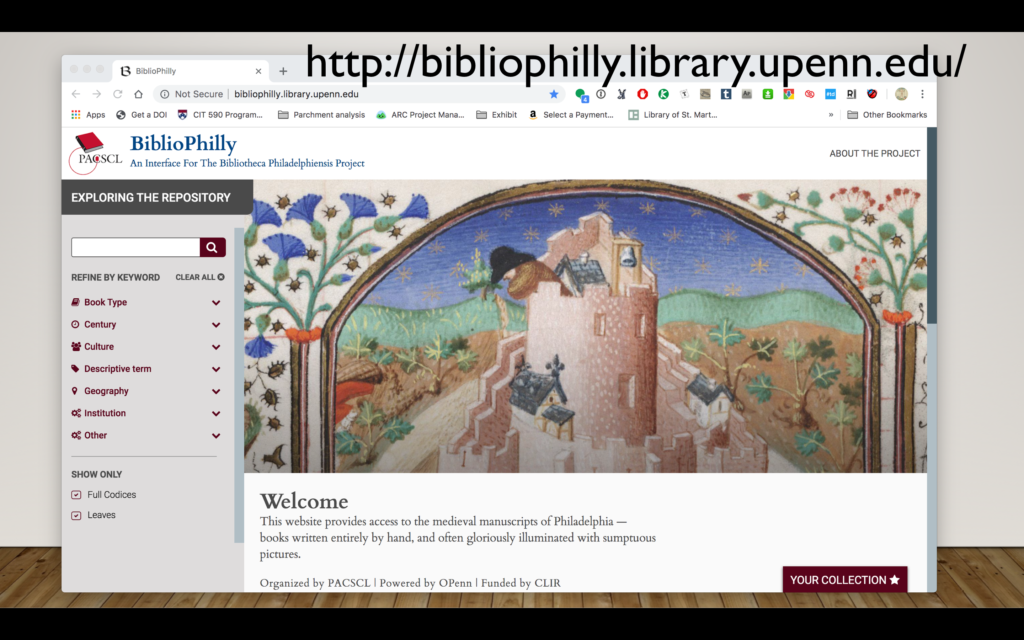

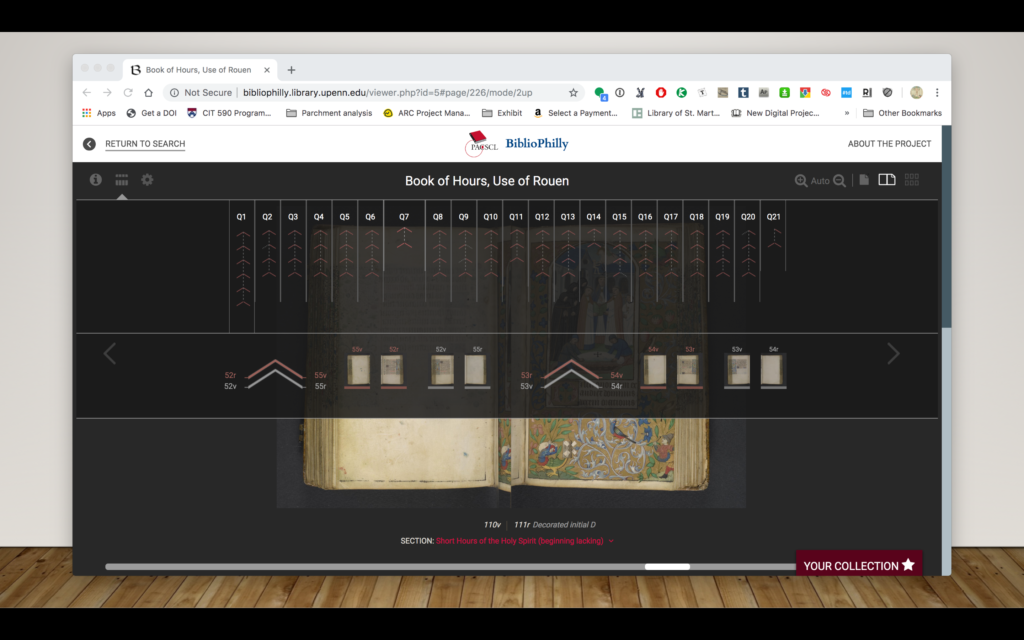

For the past three years I’ve been co-PI, along with Lois Black of Lehigh University and Janine Pollock of the Free Library of Philadelphia, of a major project, funded by the Council on Library and Information Resources, to digitize and make available the western medieval manuscripts from 15 Philadelphia area institutions – about 475 mss codices total. We call this project Bibliotheca Philadelphiensis, or the library of Philadelphia – BiblioPhilly for short. My work on the project is largely related to project management: making sure the manuscripts are being photographed on time, that the cataloging is going well (and at the start we had to set up cataloging protocols and practices). The grant, as a whole, has gone remarkably well and we’re in the process of writing the final report right now. The manuscripts went online as they were digitized, in the same manner that all our manuscripts do:

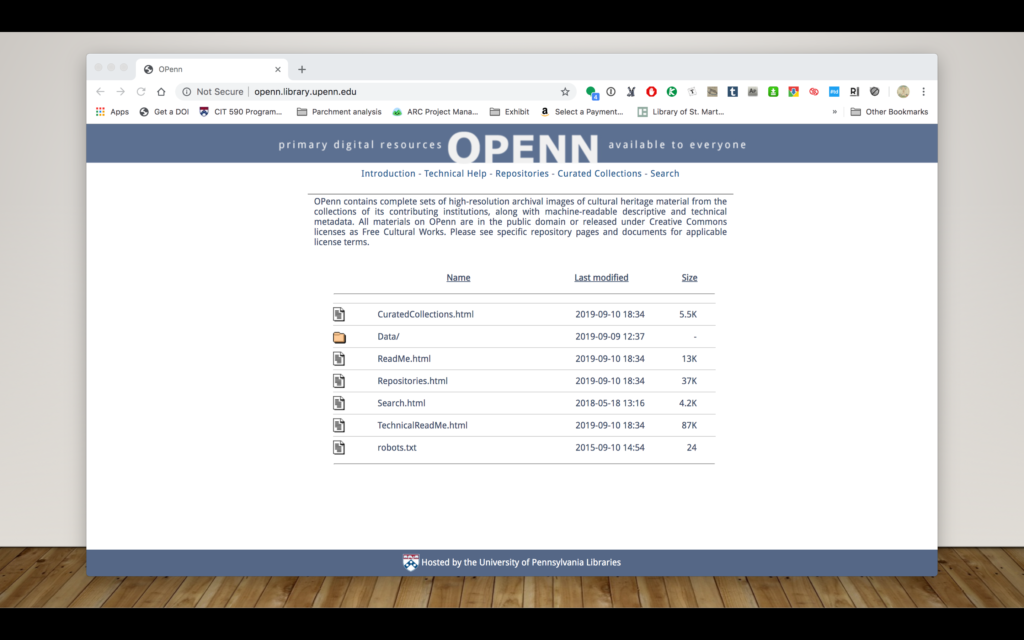

They go on OPenn: Primary Digital Resources Available for Everyone, which is a website where we make available raw data as Free Cultural Works (for BiblioPhilly, this means images, including high-resolution master TIFFs, in the Public Domain, and metadata in the form of TEI Manuscript Descriptions under CC:0 licenses – this means released into the public domain).

OPenn has a very specific purpose: it’s designed to make data available for reuse. It is not designed for searching and browsing.

There is a Google search box, which helps, but not the kind of robust keyword-based browsing you’d expect for a collection like this.

And the presentation of the data on the site is also simple – this is an HTML rendition of a TEI file, with the information presented very simply and image files linked at the bottom. There’s no page-turning facility or gallery or filmstrip-style presentation. And this is by design. We designed it this way, because we believe in separating out data from presentation. The data, once created, won’t change much. We’ll need to migrate to new hardware, and at some point we may need to convert the TEI to some other format. The technologies for presentation, on the other hand, are numerous and change frequently. So we made a conscious decision to keep our data raw, and create and use interfaces as they come along, and as we wish. Releasing the data as Free Cultural Works means that other people can create interfaces for our data as well, which we welcome.

We also have a user-friendly interface. We partnered with a development company called Byte Studios out of Milwaukee Wisconsin, which also worked with the Walters Art Museum on their site called Ex Libris (manuscripts.thewalters.org). It’s this site, which we also call BiblioPhilly, which we expect most people will use to interact with our collection. It has the browsing facility you’d expect,

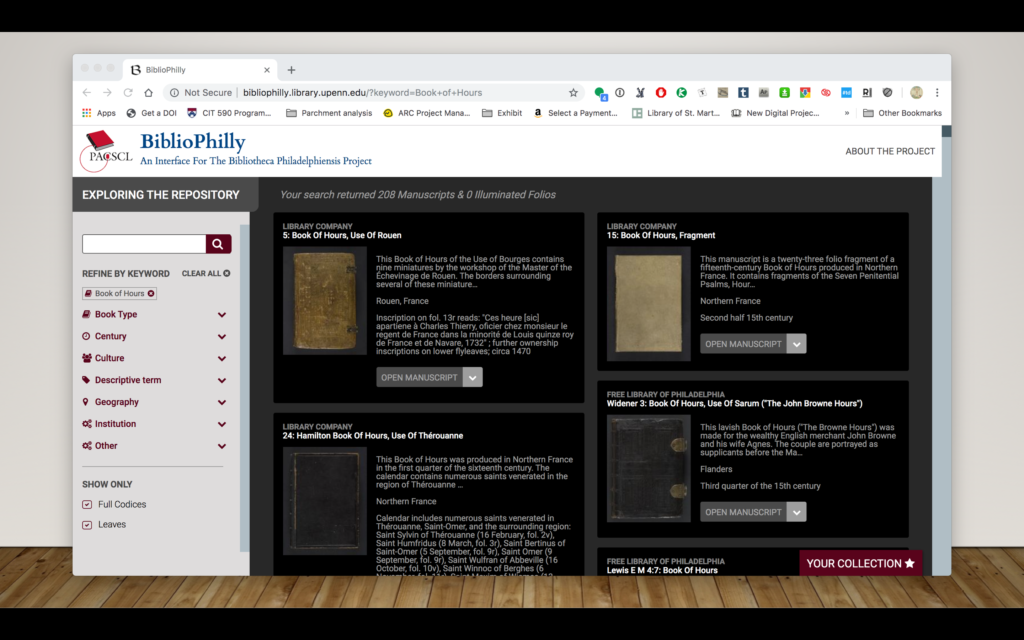

here we’re selecting a Book of Hours,

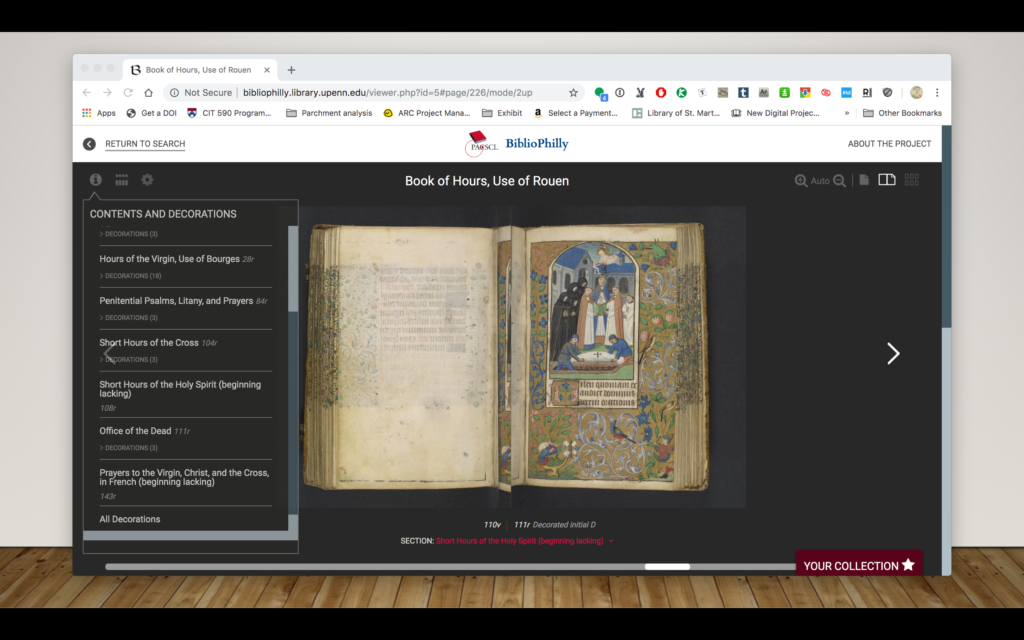

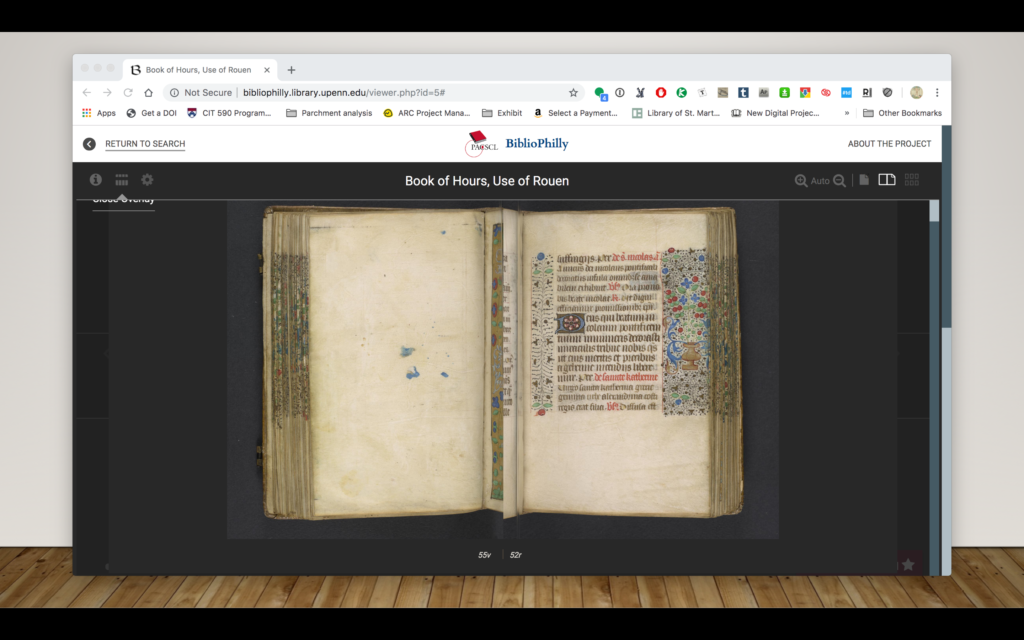

So here’s Library Company MS 5,

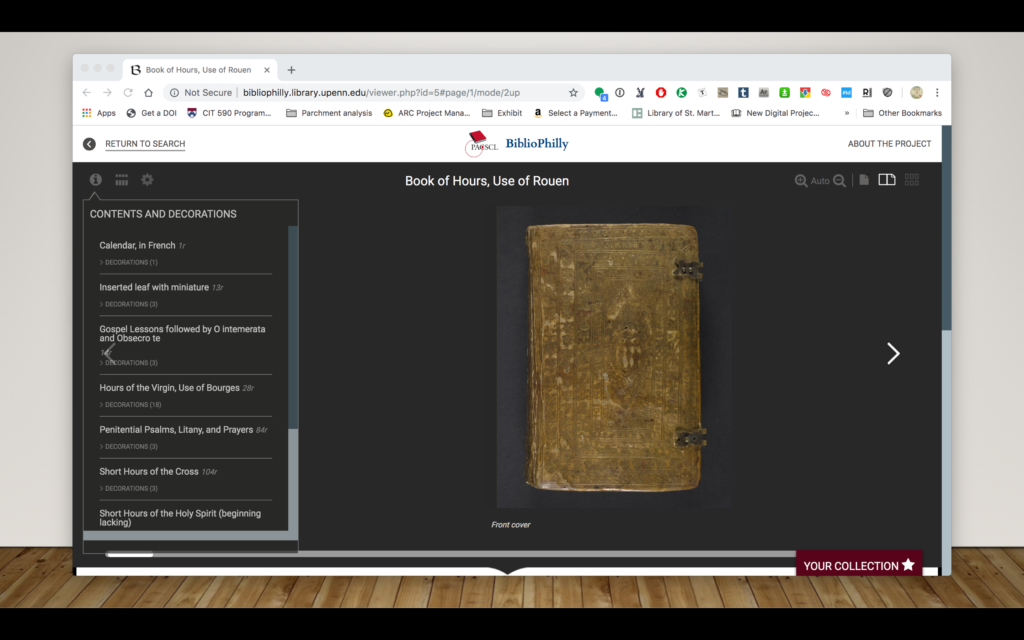

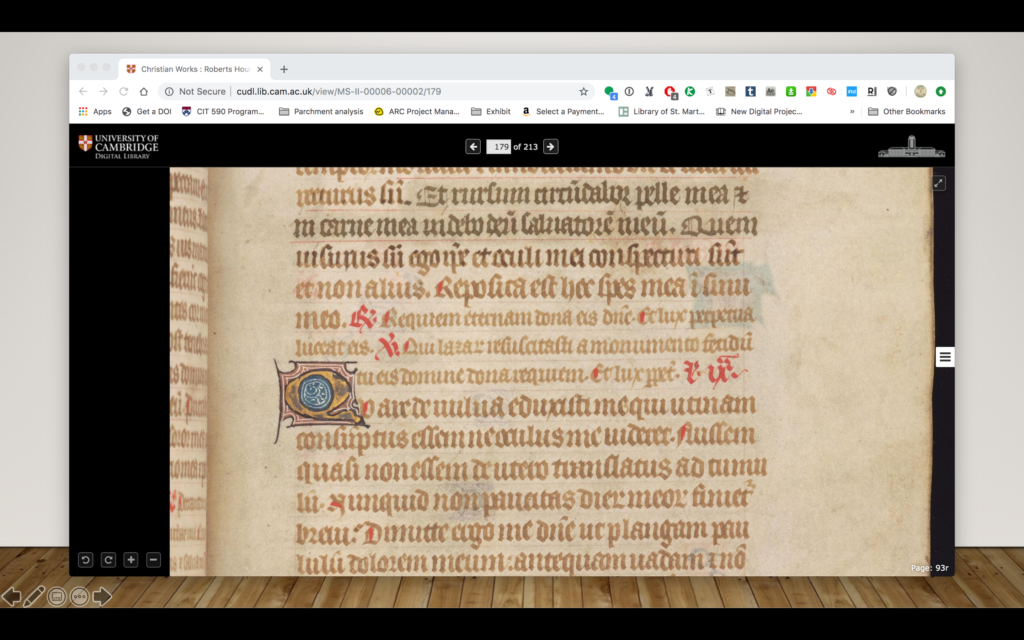

we have a Contents and Decorations menu so we can browse directly to a specific text. Here’s the start of the Office of the Dead with a miniature and an illuminated initial.

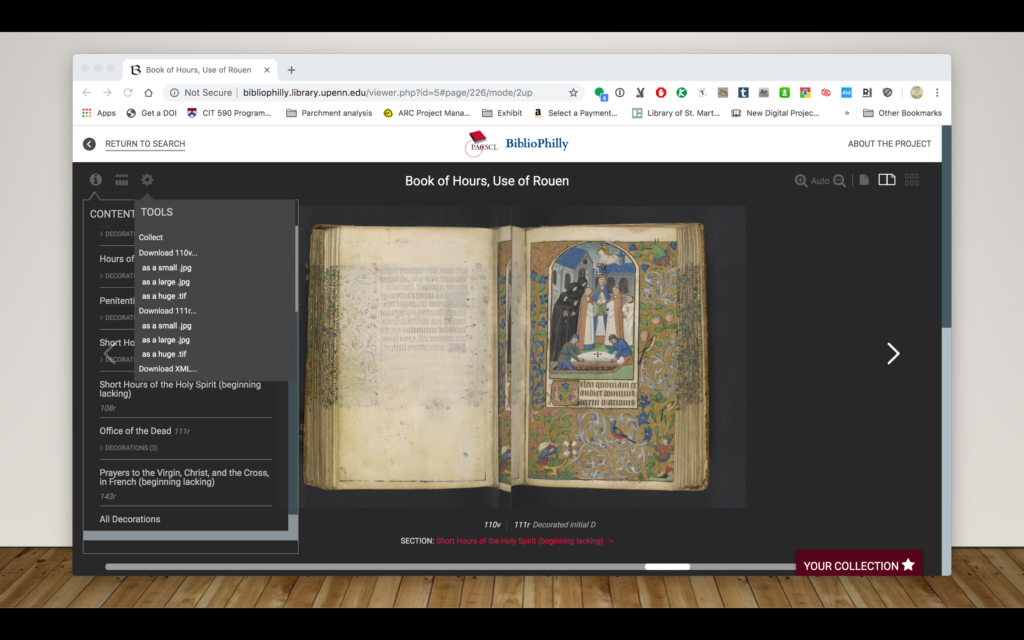

We can also download individual images or the TEI for the whole manuscript directly from this site

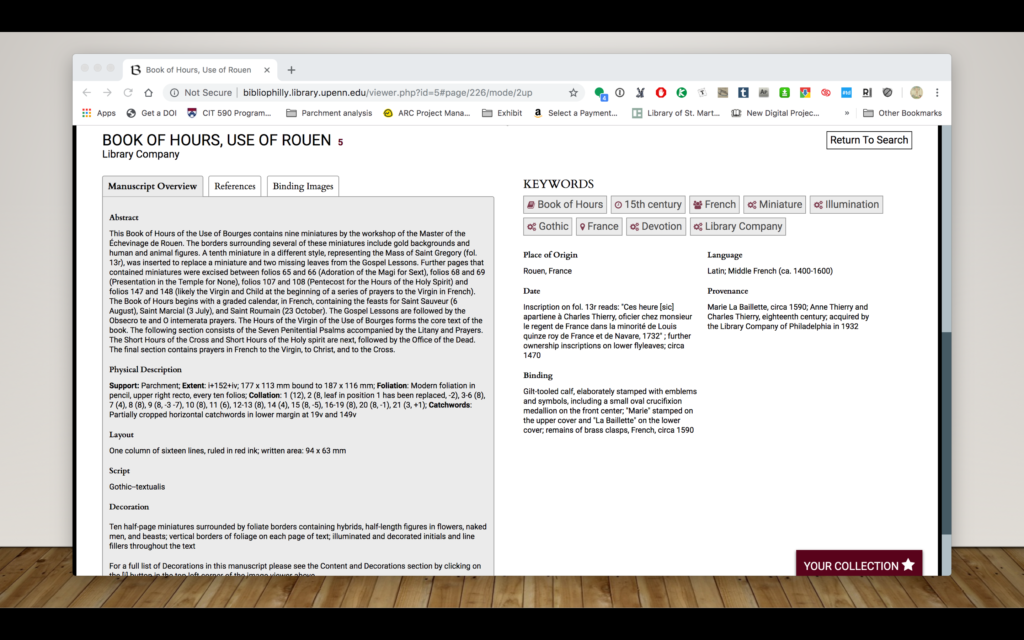

And then further down the page is all the data from the record you’d expect to see on any good digitized manuscript site. This is pulled from the TEI Manuscript Descriptions and indexed in a backend database for the site, while the images are pulled directly from their URLs on OPenn.

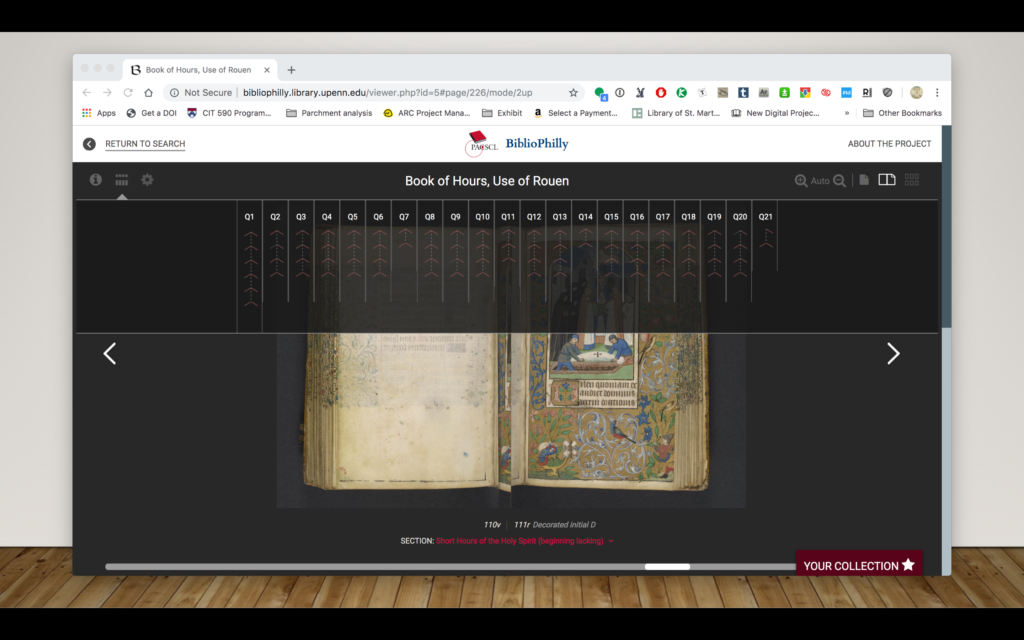

I want to return back to the top and point out the icon in the middle, which is meant to resemble the edge of an uncovered manuscript spine.

This function of the website is, as far as I know, original to BiblioPhilly, and it contains an interactive view of the physical collation of the manuscript. Initially we have diagrams of each quire, but then we can select a quire and view the bifolia diagrams separated out, and if we select one

we can view the page images that form the bilofia.

I’m showing you this both to give you a sense of the kind of work I focus on in my day to day work, but also to start to get us thinking about the concept of transformation as it applies to medieval manuscripts. Manuscript digitization and the BiblioPhilly project specifically is one example of how we transform manuscripts: through digitization we deconstruct manuscripts, breaking them virtually into individual pages and providing metadata about the object they represent (that is, the physical manuscript) as well as what we in the business call structural metadata, which is what enables us to then reconstruct some kind of digital version of the physical object. As the example of the collation view implies, it’s possible to have multiple digital versions of an object, focused on different aspects of the physical object (in this case we provide both a page-turning view that mimics the experience of paging through the manuscript, and a collation view that shows us how the manuscript would appear if we were to take it apart, as well as providing diagrams that would not be available to us if we were just using the manuscript in the reading room.

For the rest of my talk I want to think about another kind of transformation: the textual and physical transformation inherent in a group of manuscripts that dominated the manuscript trade for 250 years – Books of Hours.

Transformative Works / Language of Care

Before I do, however, I think it’s only fair to come clean. Besides my family, there are two things in the world that I love more than anything. One of them are medieval manuscripts. The other one is Star Wars. I’m a fan. I read and write fan fiction, I participate in fandom activities on and offline, I encourage other fans to create transformative works.

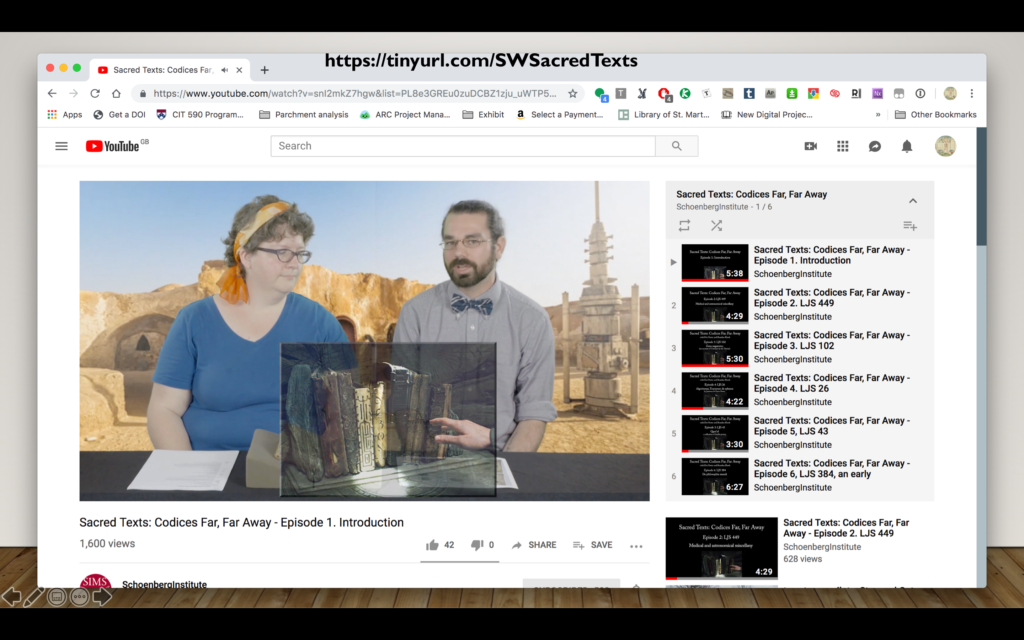

I’ve been able to combine my loves together in various ways too, from collaborating on a Star Wars fan story set in the middle ages and focusing on a group of medieval scribes,

to collaborating on a series of videos with another medievalist and Star Wars fan, Dr. Brandon Hawk at Rhode Island College, where we compare manuscripts from Penn’s collections with the “Ancient Jedi texts” shown in The Last Jedi. (Sacred Texts: Codices Far, Far Away)

So this project is another opportunity for me to combine my great loves. However, it’s also probably important to note that although I am in some sense a codicologist and manuscript scholar I am neither technically a scholar of Books of Hours – I don’t have a PhD in Art History, for example – nor am I a scholar of fandom. Which, honestly, is one of the reasons I am excited to be here with you all today, because I’m hoping that you’ll be able to help me through some of the questions I have, that I don’t yet have answers for.

Back to Transformative Works.

Transformative work is a concept that comes out of fandom: that is, the fans of a particular person, team, fictional series, etc. regarded collectively as a community or subculture. We typically talk about fandom in relation to sports, movies, or TV shows, but people can be fans of many things (including manuscripts). As defined on the Fanlore wiki:

Transformative works are creative works about characters or settings created by fans of the original work, rather than by the original creators. Transformative works include but are not limited to fanfiction, real person fiction, fan vids, and graphics. A transformative use is one that, in the words of the U.S. Supreme Court, adds something new, with a further purpose or different character, altering the [source] with new expression, meaning, or message.

https://fanlore.org/wiki/Transformative_Work

In some fandom communities, transformative works play a major role in how the members of that fandom communicate with each other and how they interact with the canon material (“canon” being the term fans use to refer the original work). Transformative works start with canon but then transform it in various ways to create new work – new stories, new art, new ideas, possible directions for canon to take in the future, directions canon would never take but which are fun or interesting to consider.

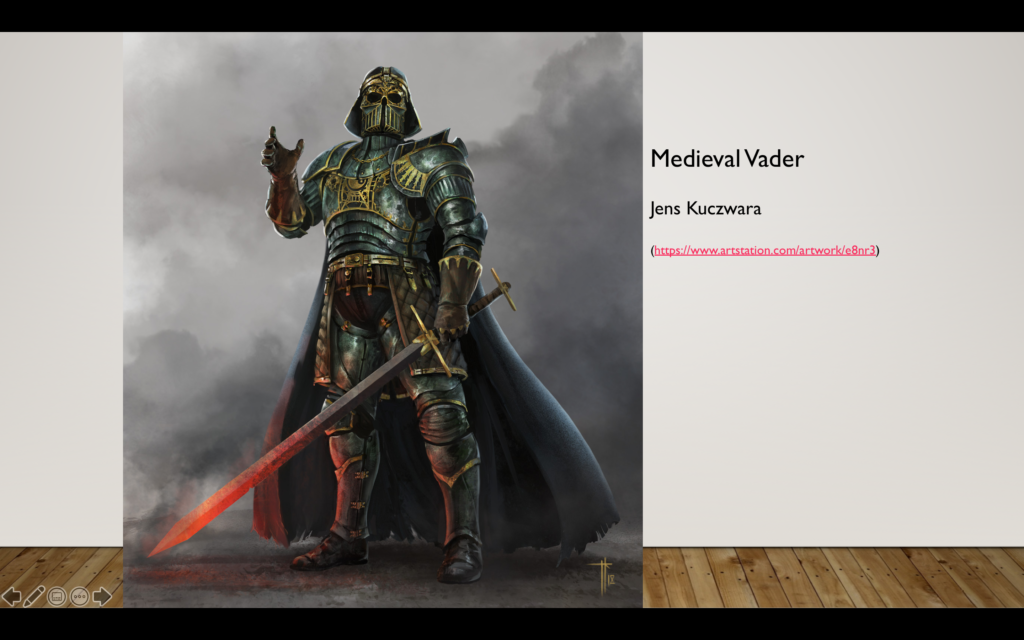

For example, Darth Vader reimagined as a medieval Dark Knight

There is a small but growing academic movement to apply the concept of transformative work to historical texts. Some of this work is happening through the Organization for Transformative Works, which among other things hosts Archive of Our Own, a major site for fans to publish their fanworks, and provides legal advocacy for creators of fanworks.

The Organization for Transformative Works also publishes a journal, Transformative Works and Cultures, and in 2016 they published an issue “The Classical Canon and/as Transformative Work,” which focused on relating ancient historical and literary texts to the concept of fan fiction (that is, stories that fans write that feature characters and situations from canon). An upcoming special journal issue on “Fan Fiction and Ancient Scribal Culture,” which will “explore the potential of fan fiction as an interpretative model to study ancient religious texts.” This special issue is being edited by a group of scholars who lead the “Fan Fiction and Ancient Scribal Cultures” working group in the European Association of Biblical Studies, which organized a conference on the topic in 2016.

You will note that the academic work on transformative works I’ve cited focus specifically on fan fiction’s relationship with classical and medieval texts, which makes a fair amount of sense given the role of textual reuse in the classical and medieval world. In her article “The Role of Affect in Fan Fiction ,” published in the Transformative Works and Cultures special issue of 2016, Dr. Anna Wilson places fan fiction within the category of textual reception, wherein texts from previous times are received by and reworked by future authors. In particular, Dr. Wilson points to the epic poetry of classical literature, medieval romance poetry, and Biblical exegesis, but she notes that comparisons between modern transformative works – that is, fan fiction – and these past examples of textual reception are undertheorized, and leave out a major aspect of fan fiction that is typically not found, or even looked for, in the past examples. She says,

“To define fan fiction only by its transformative relationship to other texts runs the risk of missing the fan in fan fiction—the loving reader to whom fan fiction seeks to give pleasure. Fan fiction is an example of affective reception. While classical reception designates the content being received, affective reception designates the kind of reading and transformation that is taking place. It is a form of reception that is organized around feeling.”

Wilson, 1.2

For my paper at the International Medieval Congress at Leeds in 2018 I described the manuscript University of Pennsylvania LJS 101 as an example of “medieval manuscript as transformative work,” not as a piece of data to be mined for its texts, but as a transformative work in itself.

Here is the manuscript in question. UPenn LJS 101 is the oldest codex we have in the University of Pennsylvania Libraries by at least 150 years and which is one of only two codices in our collection which is written in Caroline minuscule (the other one being UPenn Ms. Codex 1058, dated to ca. 1100 and localized to Laon).

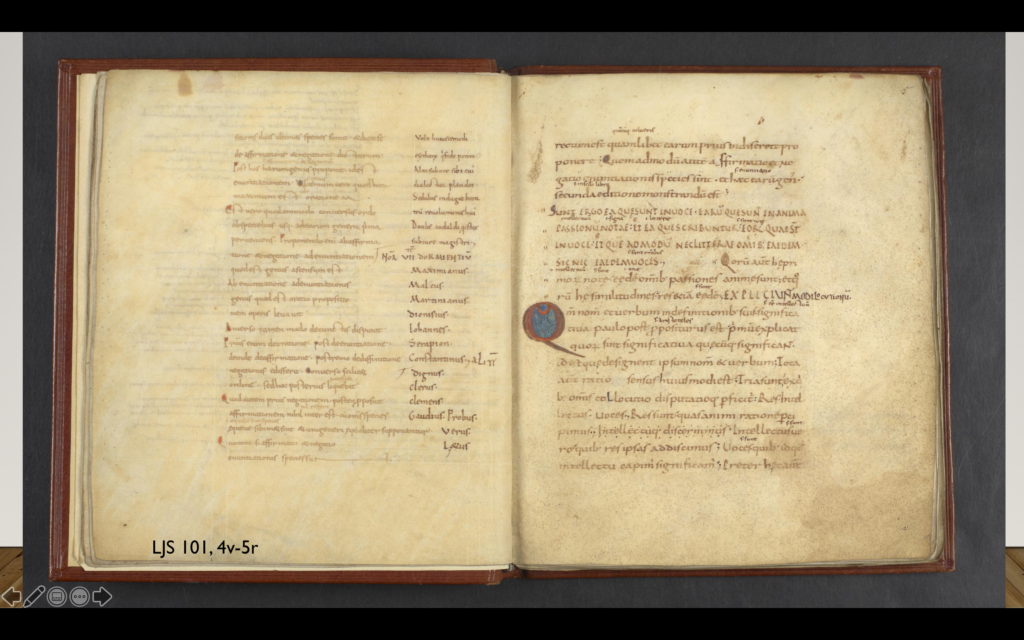

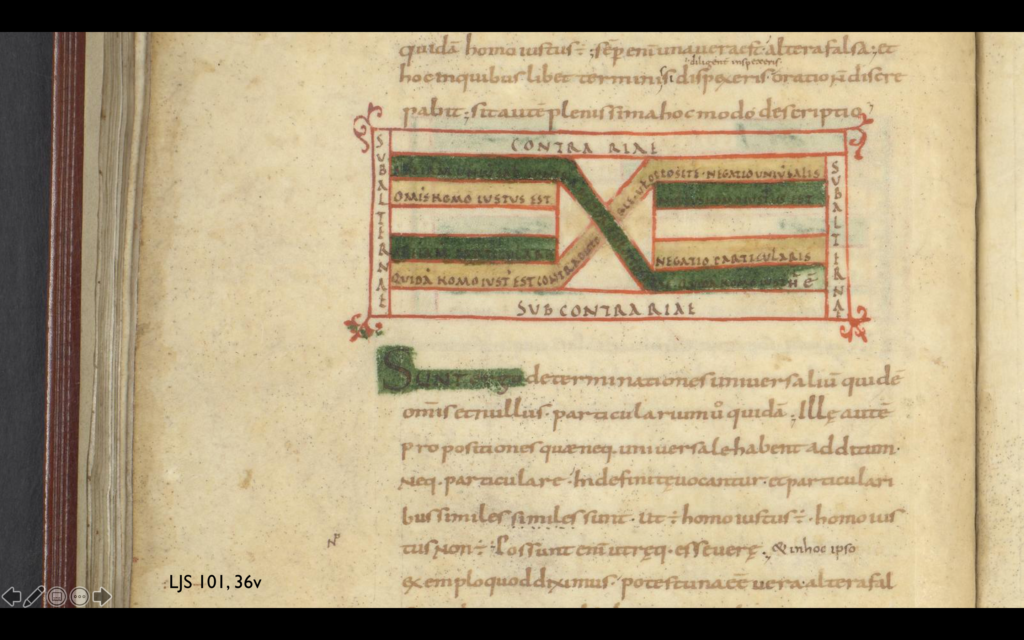

The bulk of the manuscript, folios five through 44 (Quires two through six), are dated to the mid-9th century, but in the early 12th century replacement leaves were added for the first four leaves and for the last 20 leaves. LJS 101 reflects the educational program set up in the Carolingian court by Alcuin, featuring a copy of Boethius’s translation of Aristotle’s De Institutiatione (which was commonly called Periermenias, the name also used in this text) and a short commentary on that text (also called Periermenias), along with a few other shorter texts.

Over the course of the talk I did a slow walk-through of the manuscript, examining it from cover to cover and noting every instance of a signs of care from the people who created and, for the most part, have used the manuscript since it was created.

I talked about the 19th century binding with several 20th century owner’s marks,

the 12th century replacement leaves at the front and the back of the manuscript (which notably contain all but one of the texts extant in the manuscript)

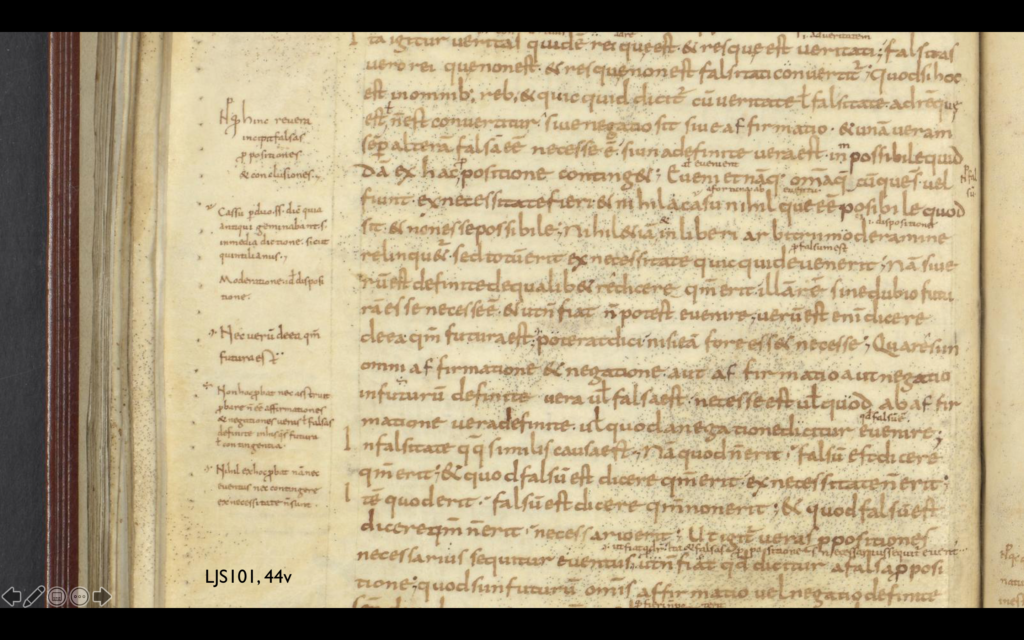

The 12th century corrections that run throughout the 9th century section

The colorful highlighting that was added to diagrams and some of the headwords

There are also many quires’ worth of text missing from the main text, and the first and last quires have been misbound in a way that makes me think someone dropped the quires, scattering the bifolia across the floor, and picked them up without paying attention to the order.

There were two things I discovered as I was working on that paper, with regard to trying to fit the manuscript into the frame of a transformative work. The first issue was what exactly is it that is being transformed. Looking again at the definition of the transformative work

Transformative works are creative works about characters or settings created by fans of the original work, rather than by the original creators. Transformative works include but are not limited to fanfiction, real person fiction, fan vids, and graphics. A transformative use is one that, in the words of the U.S. Supreme Court, adds something new, with a further purpose or different character, altering the [source] with new expression, meaning, or message.

https://fanlore.org/wiki/Transformative_Work

The thing that is being transformed is something canon – usually a text (and in text I’m including TV shows or movies), but it could be something else; an artwork, or a sports game, for example – and then there is another thing that is the transformation, the transformative work. In the case of LJS 101, one could argue that the canon is the various texts in the manuscript, but by the time they are there, they have already been transformed – they’ve been copied and recopied, edited, a scribe has decided to use this copy for their manuscript and not that one (if they even had a choice, which we can’t know), someone decided which other texts to include. If I argue instead that the canon was the 9th century version of the manuscript – as it existed when it was created – and the version we have now is the transformative work, I find that a bit more satisfying, although there’s still another problem.

I’m not comfortable applying Dr. Wilson’s concept of affective reception to the people who created and worked with LJS 101 – I didn’t want to suggest that these people loved the manuscript the same way that I do – but I did want to explore the idea that this person or people cared about it, and that other people have cared about this manuscript over time enough that it survives to live now in our library at the University of Pennsylvania. Their interests may have been scholarly, or based on pride of ownership, or even based on curiosity, but whatever their reasons for caring for the manuscript, they did care, and we know they cared because of the physical marks that they have left on these books. Manuscripts that survive also often show examples of lack of care, damage and so forth, so those elements need to be included in this framework as well. So coming out of that paper I suggested a language of care around their use, rather than the frame of Transformative Work.

After Leeds, I spent some time wondering if there were actually a way to make the frame of Transformative Work fit any medieval manuscript, or if it was just another one of my zany ideas. But in the fall, when I was teaching an undergraduate course on medieval manuscripts with Dr. Will Noel, the director of the Schoenberg Institute and the Kislak Center, I had a bit of an epiphany as he was lecturing on Books of Hours. He made the very important point that people saw Books of Hours as at least part of a ticket to salvation. As I will describe in a moment, Books of Hours are organized around the veneration of the Virgin Mary, who acts as an intercessor between us and Christ. By using Books of Hours to ask Mary to intercede with us for Christ, we hope to spend less time in purgatory and to make to heaven, to be with Christ, sooner than we would otherwise.

I still thought this idea was a bit weird, so I sat down with my colleague Dr. Nicholas Herman, the SIMS Curator of Manuscripts, and talked about the potential of manuscripts as transformative works, and he reminded me that, unlike LJS 101, which really only works as a transformative work in a physical sense, Books of Hours can work both textually and physically. What do I mean by this?

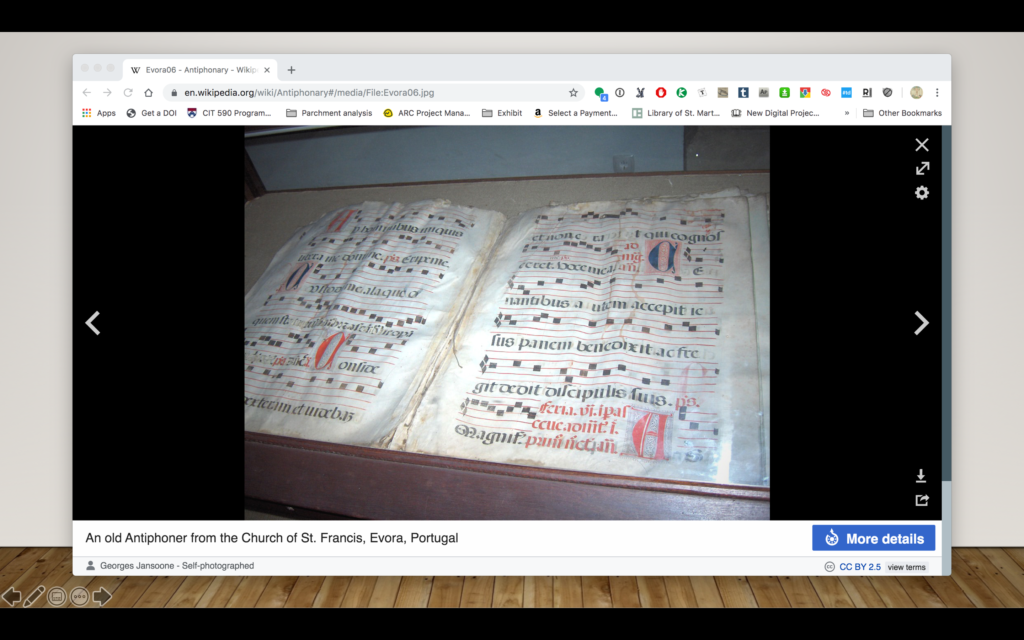

Textually, Books of Hours are designed to be lay versions of the texts that priests, monks, and nuns used during their lives in the Church. Churches, cathedrals, and monasteries had antiphonaries – containing liturgical chants – and breviaries – books furnishing the regulations for the celebration of the canonical Office – for the use of their communities, usually very large books that the members of the community would share as they sang and recited prayers together.

Historians trace the growth of Books of Hours to the late 13th century, when social and economic changes led to both a growing secularization and an embryonic urban middle class, which emerged through the 14th and 15th centuries. Speaking generally these groups – although small – had money, and they were both literate and interested in books. They were also pious. In Time Sanctified, Roger Wieck explains that the laity at this time wished to imitate the clergy by adapting their prayers, adapting their books, and by adopting their direct relationship with God. The book of hours gave them all of these things: “a series of prayers like the clergy’s, but less complex, and a type of book like the breviary, but easier to use and more pleasing to the eye.”

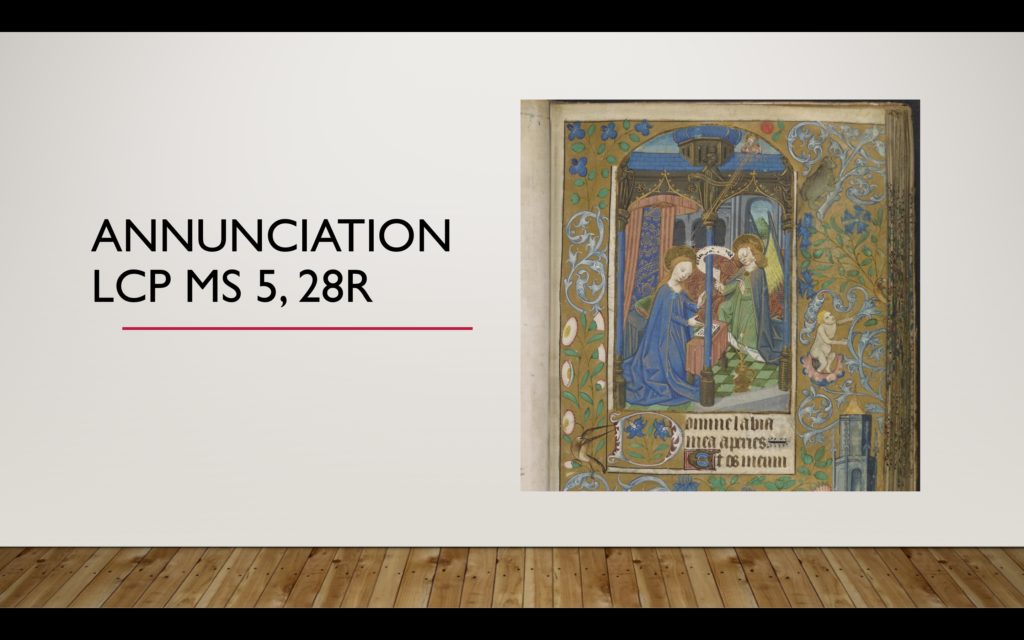

The growth of the cult of the Virgin around this same time also contributed to the development and popularity of Books of Hours. Indeed, the thing that determines whether a prayer book is a Book of Hours or some other type of prayer book is the inclusion of the Hours of the Virgin. The Hours of the Virgin did not come into the common use before the 10th century although it may be older, and it was added to breviaries in various monastic orders throughout the 11th and 12th centuries. The Hours of the Virgin were extracted from the breviary and became the centerpiece of the Book of Hours: a set of prayers to Mary, designed to be recited daily and throughout the day – eight times, roughly following the canonical hours that would be practiced in a monastery – an ongoing reminder of the pious life of the user of any given Book of Hours.

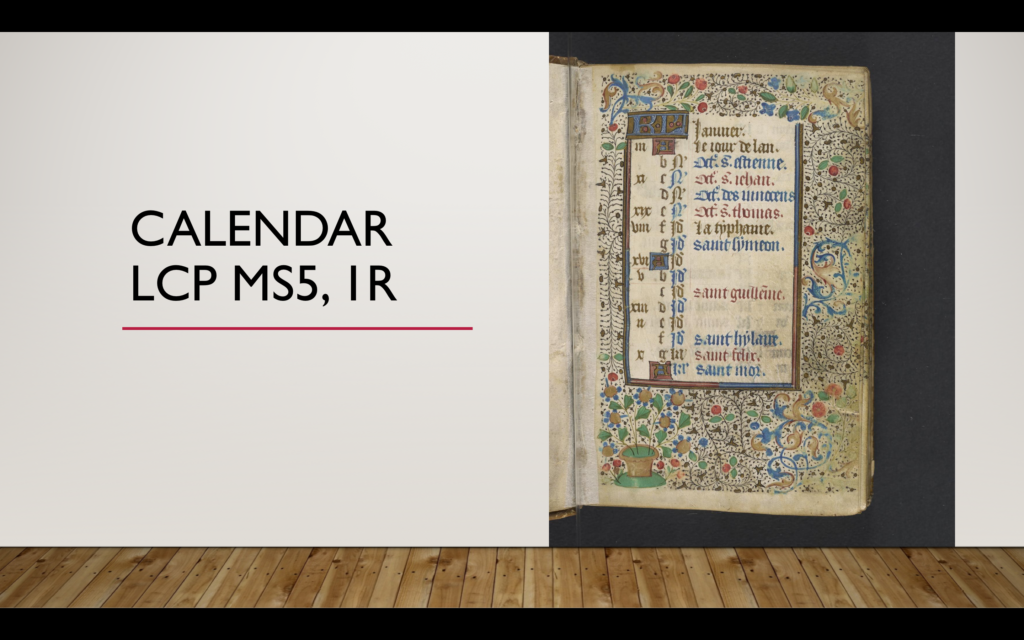

In addition to the Hours of the Virgin, Books of Hours will typically include a Calendar, which will list festivals and saints’ days presumed relevant for the geographical location in which the owner of the book resides; The Gospels; the Hours of the Cross and Hours of the Holy Spirit; two prayers to the Virgin known as the Obsecro te and the O intemerata; the Penitential Psalms and Litany; the Office of the Dead; and various and perhaps numerous Sufferages.

The Hours of the Virgin were pulled from existing monastic or liturgical books, but so were other parts of a typical Book of Hours – the Calendar, the Office of the Dead, and of course the Penitential Psalms. Other elements, including the Hours of the Cross and Hours of the Holy Spirit, the Obsecro te and the O intemerata, and the Suffrages have uncertain sources although it’s unclear in my research whether they were original to Books of Hours.

Returning to the frame of Transformative Works, here we have Books of Hours, as a class or type of books, that represent a transformation of canonical liturgical texts originally developed for clerical and monastic users, into texts that are explicitly for lay use, and this transformation was explicitly made from a place of affection on the part of the people doing the transforming. One could thus argue that Books of Hours are transformative works of liturgical works.

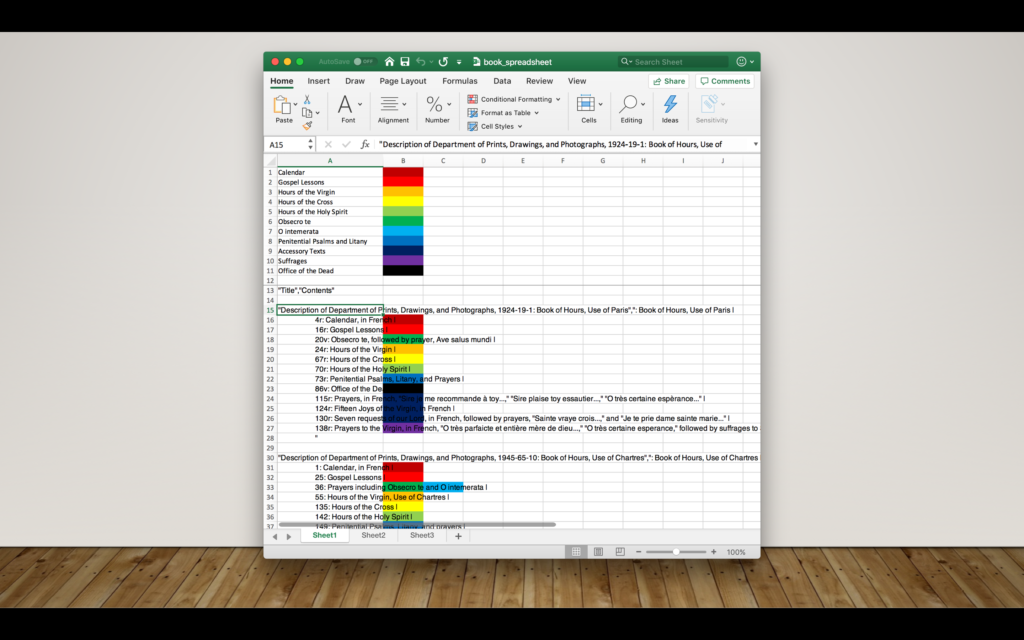

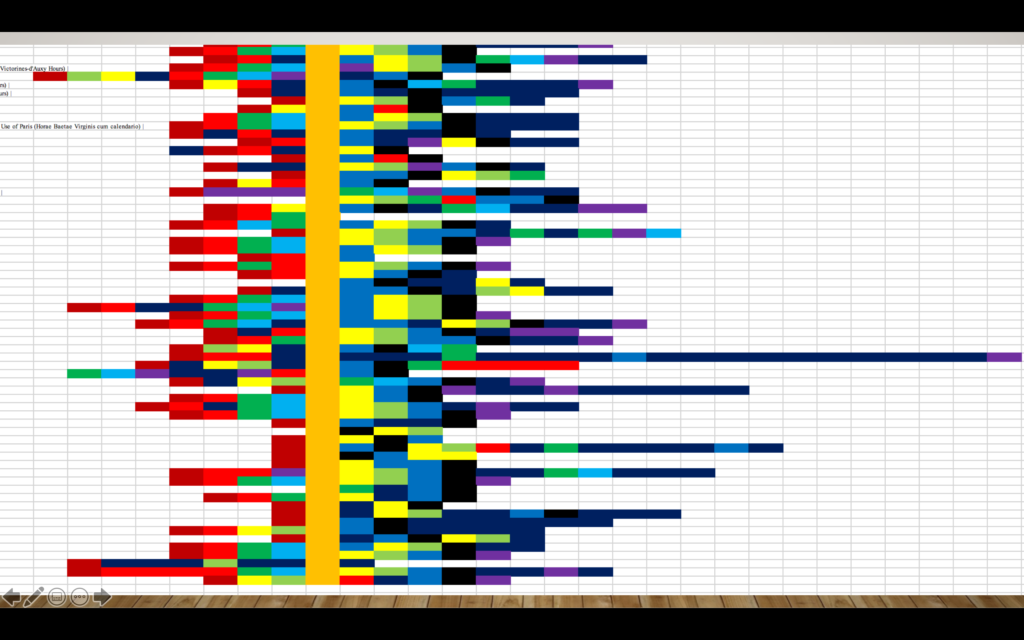

But that’s looking at Books of Hours as a class. What about transformation within the class? Although as I explained earlier Books of Hours usually contain a set group of texts, and they usually appear in a set order, my theory coming into this is that, in practice the textual organization of individual Books of Hours is much more variant. So I did a bit of work, using data from OPenn, to visualize the variance across a collection of Books of Hours.

Through OPenn, I have access to three collections of digitized Books of Hours: those digitized through the Bibliotheca Philadelphiensis project, those digitized through The Digital Walters, which is the ongoing digitization project at the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore – the data for which is hosted on OPenn – and the collections of Penn Libraries itself. As part of the data publication, OPenn hosts spreadsheets that list all the manuscripts in a given repository or collection, so it was simple enough for me to filter for only those titles that include the word “Hours”, check for stray odd things, and then use some scripts I wrote to generate a new spreadsheet that pulls out the contents of each of these manuscripts. Then I color coded each text to align with the list of texts in the “usual” order prescribed by Roger Wieck in Time Sanctified.

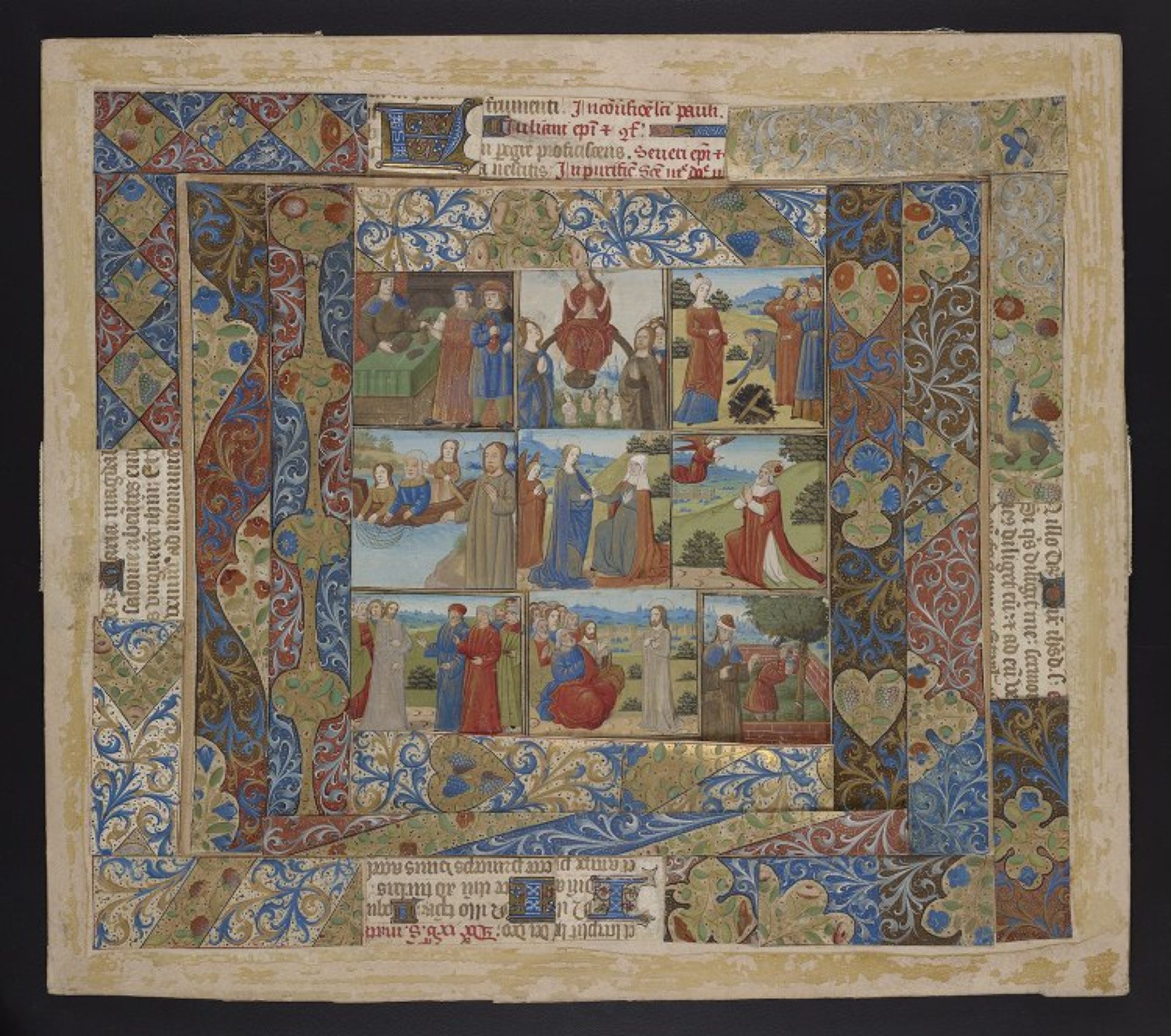

Here are the first couple of books of hours, and you can see that the texts in both are in a slightly different order than the “usual” order.

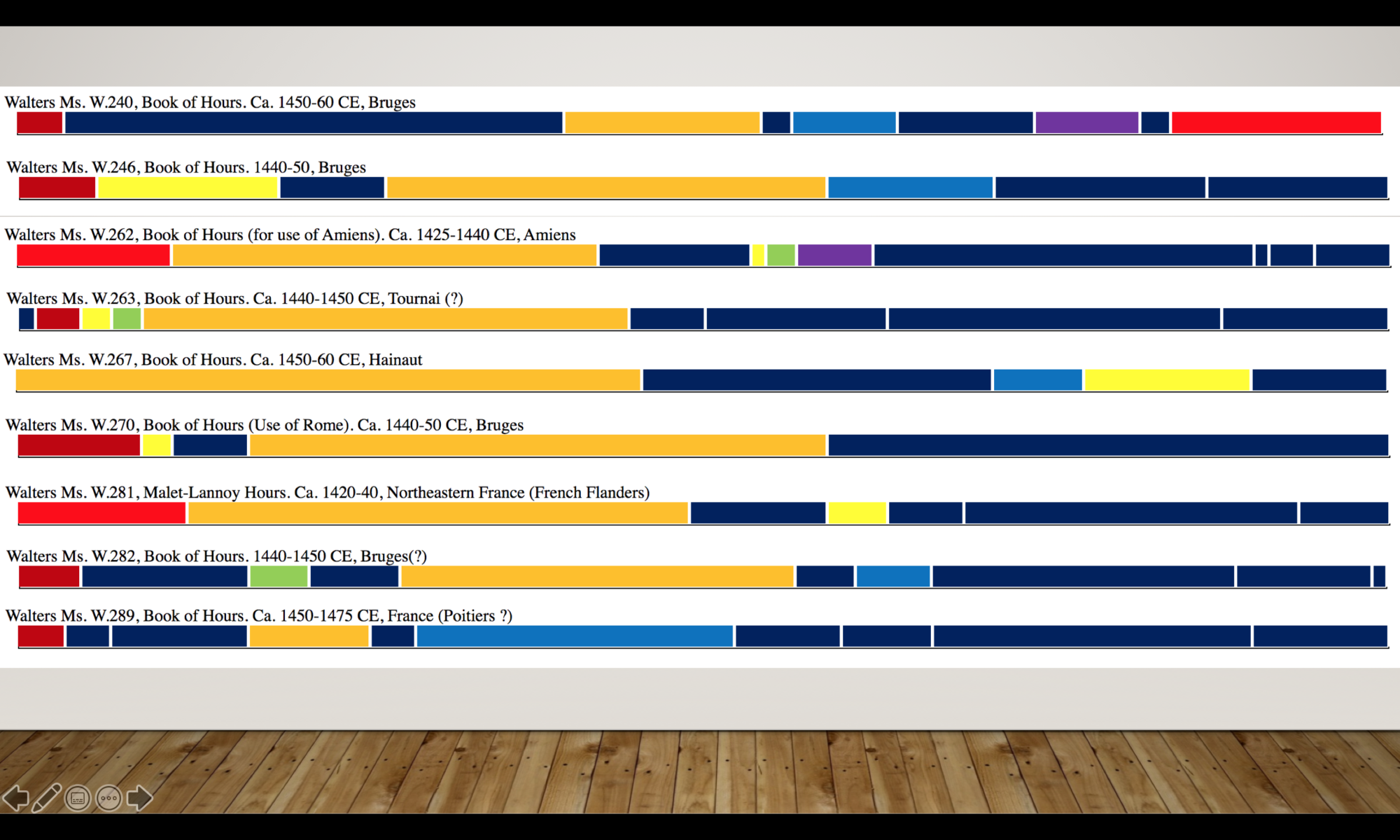

To more easily view the variance I turned the color charts on their side, placing each manuscript in a row, and stacked them. The Hours of the Virgin are the gold bar down the center; I did it this way because the Hours of the Virgin are the central text of Books of Hours and it made sense to visualize the other texts around that one. The rest of the contents are arranged around that text. We can see that the area before the Hours of the Virgin tend to be warmer, and the area after the Hours of the Virgin tend to be cooler, there is an awful lot of variation there. Unfortunately this chart isn’t organized in a thoughtful way; There are a mix of uses represented here, including Paris, Rome, Sarum, Franciscan, Bourges, and Utrecht, among others, and they range from the 14th through the 16th centuries, mostly from France and the Netherlands, but they aren’t ordered, and that’s definitely something that would need to be addressed in future use. The chart also doesn’t take into account any physical modifications that might have been made to the individual manuscripts, modifications that could lead to texts being reordered at some point after the book was written.

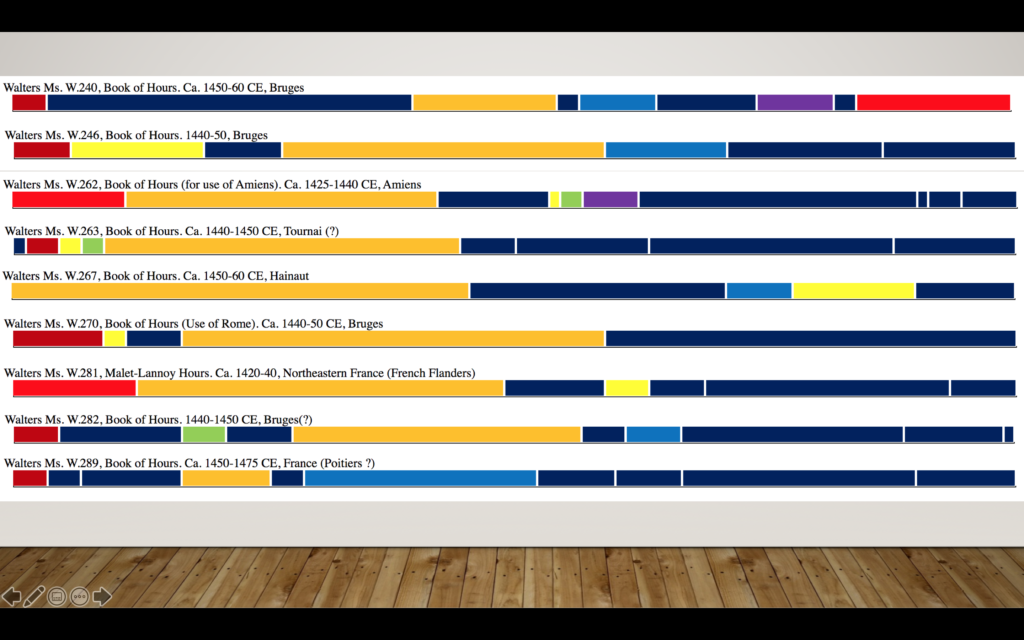

This view also doesn’t take into account the actual or relative length of the books, so I tried another way to visualize the texts.

In this example, Books of Hours from the Walters Art Museum, each book has its texts distributed across a row, which is the same length for each book. Again the Hours of the Virgin are in gold, with the other texts colored appropriately, but because the gold bar of the Hours of the Virgin appear very long in some, and short in others – assuming that the Hours of the Virgin is approximately the same in each manuscript – you get a better sense of the size of the books in number of folios from this visualization.

So we’ve looked at Books of Hours as transforming from monastic liturgical texts to texts used by laypeople, and then at the transformation of those texts in terms of which are included and which left out, across a collection of Books of Hours. I want to close by talking very briefly about a third way in which Books of Hours might be considered transformative works: physical modifications made to them, both on purpose and accidentally, after their creation and as a result of their use.

Physical

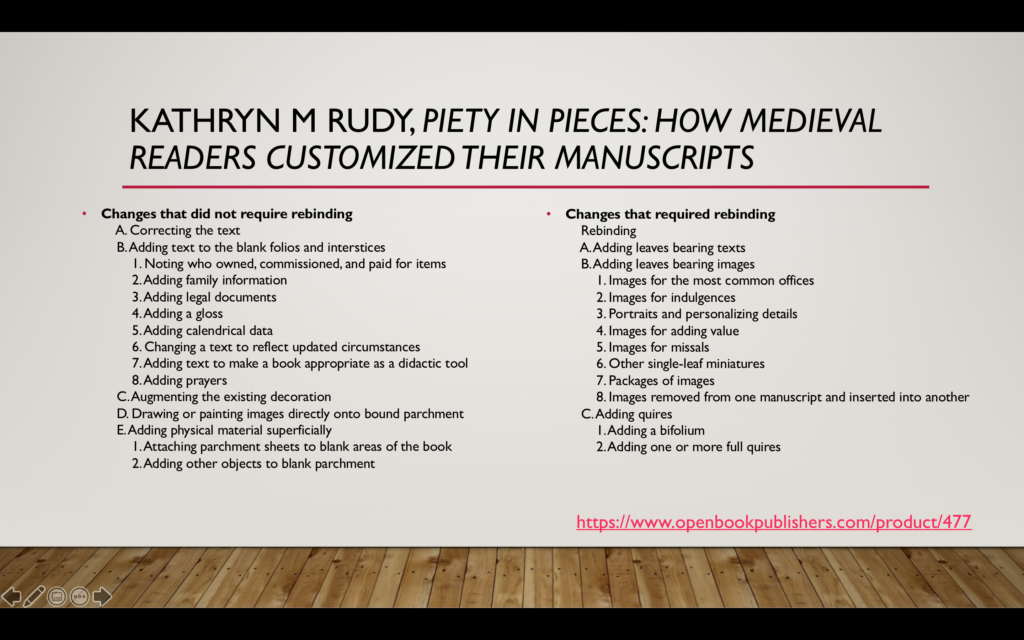

For several years now Dr. Kathryn Rudy at the University of St Andrews has been doing important and cutting-edge work on how people in the medieval and early modern periods physically interacted with their books, particularly their prayer books. In this section I’ll talk about two of her studies that are particularly relevant to the concept of Books of Hours of transformative works.

In her book Piety in Pieces: How Medieval Readers Customized Their Manuscripts, Dr Rudy classifies the many ways in which the owners of Netherlandish prayerbooks modified these books over time. In the introduction, she points out that it’s often difficult if not impossible to understand exactly why some of these changes were made, but clearly some of the possible reasons lie within the realm of Wilson’s definition of affection. Rudy says:

“In this study I explore the ways in which medieval book owners adjusted the contents of their books to reflect changed circumstances. Such circumstances were not usually so overtly political, but they nonetheless reveal other fears and motivations. Religious, social or economic reasons could also motivate such emendations. Augmentations to a book reveal strong emotional and social forces.”

Dr Rudy divides the modifications into two groups, those that require rebinding and those that don’t, and comes up with a detailed variety of changes, which I list here. This list includes many ways that people changed their prayer books, from changing the text in various ways

(in this example, an owner found an error and had a professional scribe fix it) to adding new leaves or removing old ones. This list isn’t even exhaustive – Dr Rudy’s study also includes sections on modular design – where prayer books were built from modules that were designed to be modified on spec, either during the time the book was being made or after – and on modifications that led to complete overhauls of books; for example, building books out of quires that were originally part of other books.

Most relevant for the discussion of Books of Hours as transformative works and the accompanying concept of affective reception is Dr Rudy’s final chapter, in which she lists the reasons that changes might have been made – reasons that she refers to as patterns of desire.

“I have asked in this study: how did later users register their opinions that a book considered perfectly acceptable by its previous owners was for them somehow incomplete, and by what means did they express their discontent? How can their acts of recycling and upcycling be interpreted? The kinds of augmentations owners made to books reveal certain patterns of desires, which I enumerate here.”

Although these desires vary significantly from the kind of affection that I’ve discussed earlier in the paper – which focused on the love of the Virgin Mary and the desire to reach God (so, I suppose, aligns most clearly with “H. Fear of Hell”) – these other desires also reflect affection of various sorts.

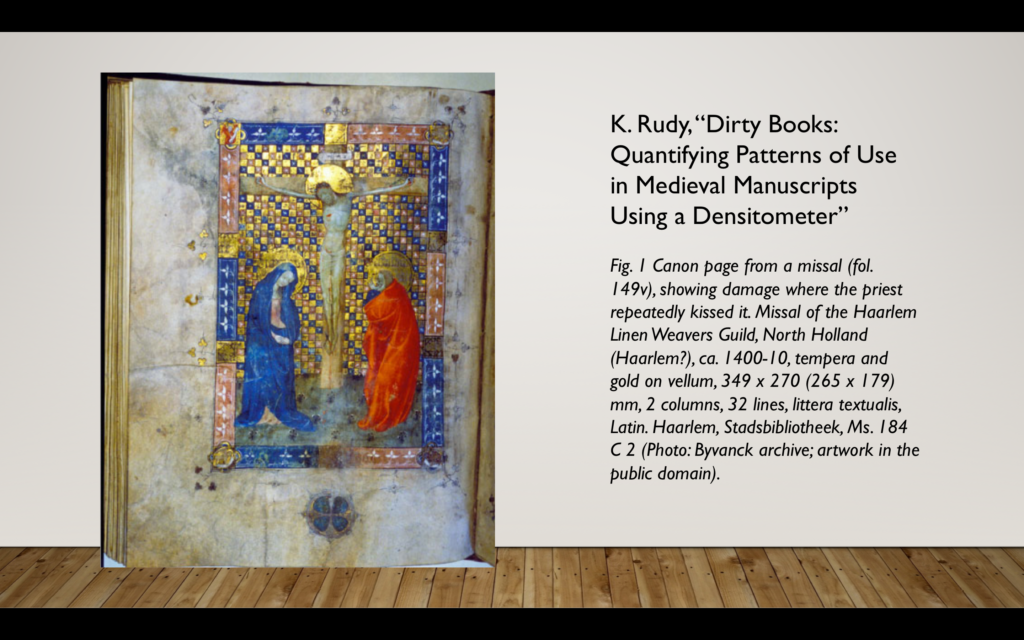

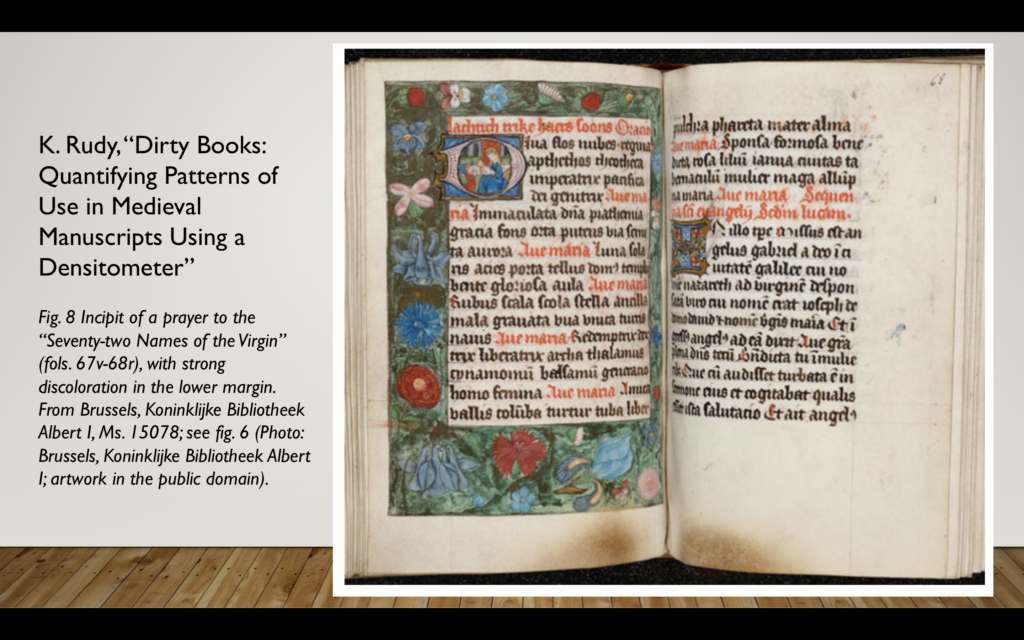

One of Dr Rudy’s other studies focuses on densitometry, or the quantitative measurement of optical density in light-sensitive materials. It is a simple fact that medieval and later users of manuscripts leave traces of their use of manuscripts in the form of dirt around the edges of pages, and sometimes on decorations and illustrations as well. More use would deposit more dirt, more dirt would make an area darker, and that darkness vs. the lightness of the rest of the page can be picked up using a tool called a densitometer. Dr. Rudy used a densitometer to measure the distribution of dirt through a number of Netherlandish prayer books and first published her findings in “Dirty Books: Quantifying Patterns of Use in Medieval Manuscripts Using a Densitometer,” in the Journal of Historians of Netherlandish Art in 2010. Her conclusion was that in applying densitometry to prayer books, one might be able to determine which pages – and thus which texts – users of those books turned to the most.

While my concern with the care of LJS 101 focused on how it was manipulated by later users – by how they bound it, notated it, cared for it in a physical sense – Dr. Rudy’s use of densitometry is designed to determine which prayers the people who actively used the prayer books recited most frequently. It’s a physical indication of religious practice – Dr Wilson’s affective reception.

Here are just two examples from Dr Rudy’s article. This first is from a Missal – a liturgical book, not a personal prayer book – That shows where a priest (or perhaps priests) kissed the illumination enough to damage it. This circle and cross at the bottom of the page is an osculation plaque, which was designed to be kissed and touched in place of the illumination, as artists knew that their work would be the object of veneration. So that plaque has been well-worn, but the priest wandered, at times reaching up as high as Christ’s feet.

In addition to measuring the wear of illuminations to see how people caressed their books, Dr Rudy used densitometry to measure dirt on the edge of pages. These pages show very heavy discoloration in the bottom margins, which implies that someone (or many someones) held the book open frequently to this page, which contains the incipit of a prayer to the “Seventy-two Names of the Virgin.”

Someone loved the Virgin Mary, so they returned to this page again and again to read this prayer, thereby physically changing the book with the addition of dirt from their fingers. This book is one of many that contain approximately the same texts, in the same approximate order, but each of which was designed and written to be used by individuals for prayer and contemplation. And finally this type of book, the Book of Hours, was a transformation of liturgical texts into something that individuals could use for prayer in their own lives.

Thank you