Presented by Dr Brandon Hawk and Dot Porter at Books on Screen: A Virtual Symposium, University of Leeds and Anglia Ruskin University, November 3, 2021

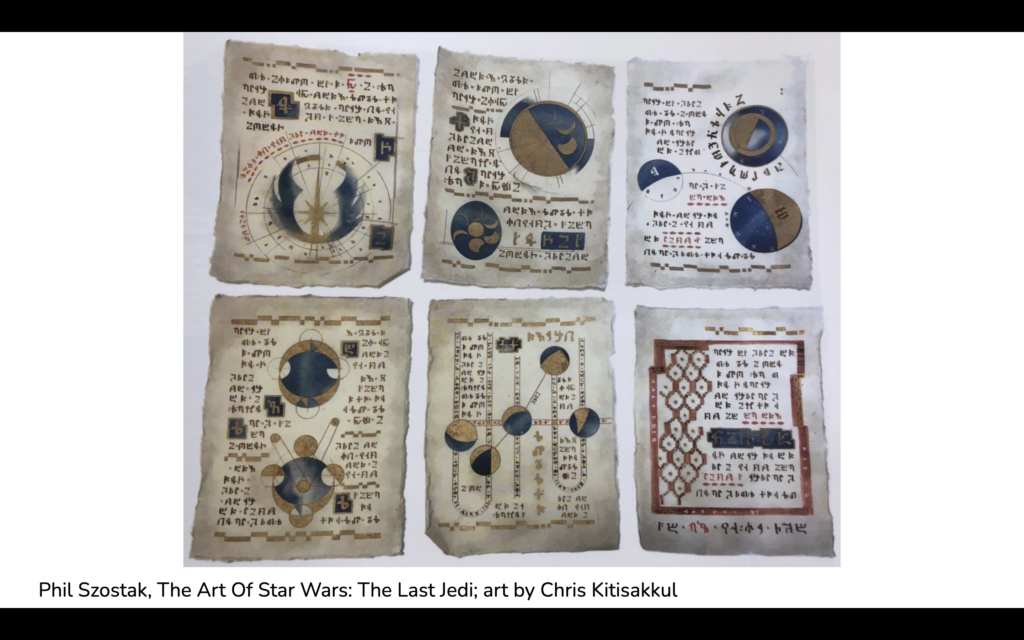

With the premier of Star Wars, Episode VIII: The Last Jedi, fans saw the first glimpses of books in the beloved galaxy far, far away. Although text technologies had been present in Star Wars media before, usually on screens in-universe, the Jedi library on Ahch-To was the first time that books had been represented as codices in the Star Wars saga. Since then, much more has emerged about the sacred Jedi texts, in art books, comics, interviews with the creators, and more. What is apparent, most of all, is that the sacred Jedi books are modeled on actual medieval manuscripts from around the world. In this presentation, we build upon our previously successful video series titled Sacred Texts: Codices Far, Far Away.

We will highlight some of the most significant medieval manuscript genres that parallel the Jedi codices and discuss how those books intersect with other recent Star Wars media, such as lore about the World Between Worlds as seen in the Star Wars Rebels TV show. We especially aim to highlight the intersection of spirituality (religion) and science (technology) as seen in both medieval manuscripts and the Jedi codices. Our aim is to use such connections from medieval sources to sci-fi medievalism as a way to discuss the relevance of the past for understanding storytelling in our own culture.

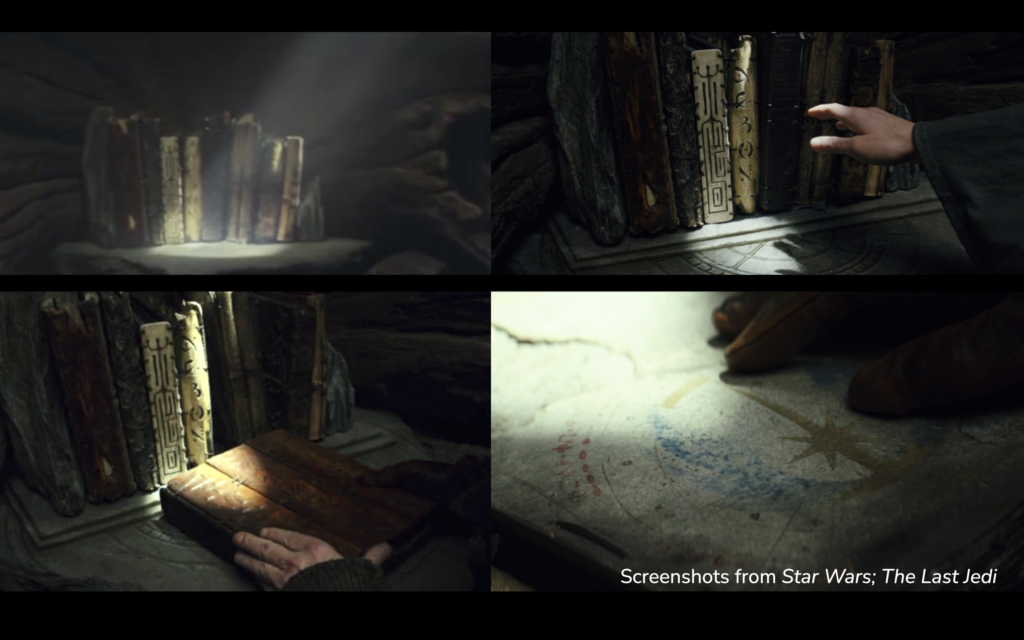

Our first glimpse of the Jedi texts appears in The Last Jedi, just as Rey, our heroine, first sees them. Rey has been sent to the island of Ahch-to to bring Luke Skywalker back to help the Resistance, led by Luke’s sister General Leia Organa, to defeat the First Order. Rey has been there for a day or so, following Luke around, making no headway, when she hears a voice calling her to the Uneti tree, a large, hollow, Force-sensitive tree that houses these manuscripts. It’s in the company of these books that Rey and Luke finally communicate with each other, when Rey admits that she has only recently come to the Force and that she needs Luke to train her to be a Jedi, and when Luke grudgingly agrees to give her some lessons, but also tells her that the Jedi must die. Exciting stuff, and the books are there to hear it.

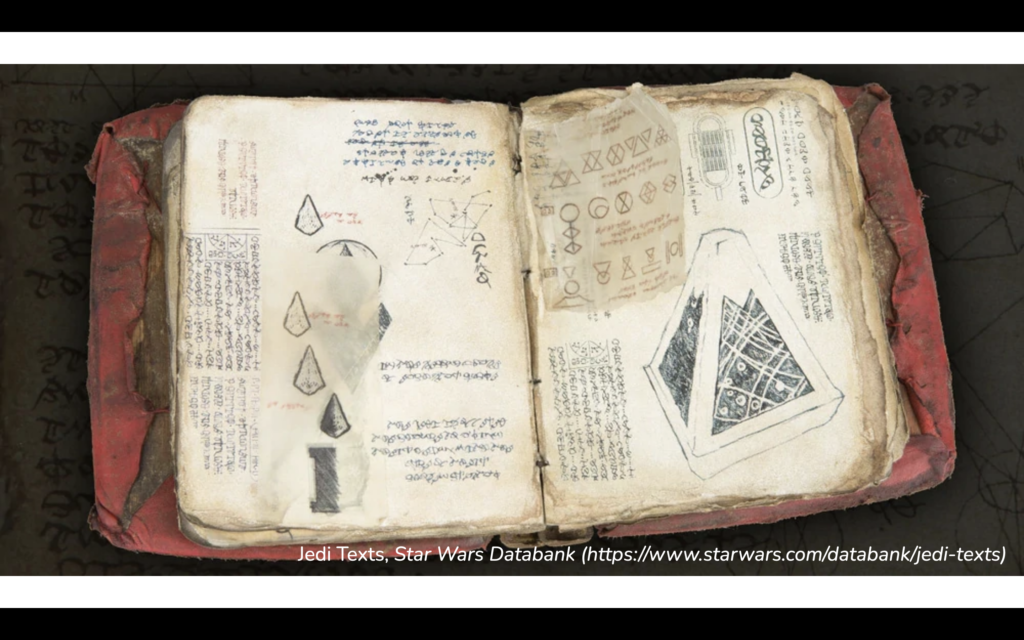

According to Star Wars The Last Jedi: The Visual Dictionary, Luke Skywalker scoured the galaxy for these texts and collected them himself, storing them in the tree that we see in the film. So these texts weren’t originally all in one collection, they are from many different planets, potentially written in ten different places, ten different times, ten different languages and alphabets, although we only see the interior of one of them in the film.

Since the release of The Last Jedi, more knowledge about these books has been added in various Star Wars merchandise, including comics and art books. For example, in the Poe Dameron comic, issue #27, we learn that Rey has been working with C3PO to translate the texts.

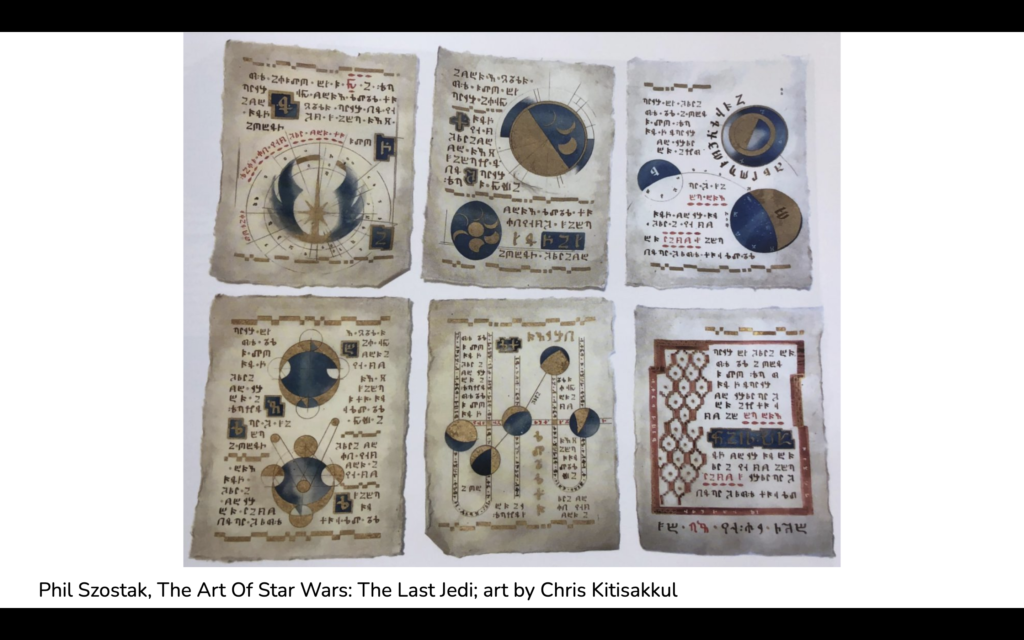

The best summary of what we know about the Jedi texts (canonically, that is) is found on the Wookieepedia page. We learn that the books include works titled the Aionomica, Chronicles of Brus-bu, Rammahgon, and the Poetics of a Jedi. As the Wookieepedia page says, the Jedi books “describe the tenets and history of the Jedi, and give specific guidance to those studying the path of the Jedi. Future students were encouraged to add to the books over millennia.” As we can see, and as we’ll see in more detail later, some of the pages of these books contain what appear to be various pieces of astronomical knowledge.

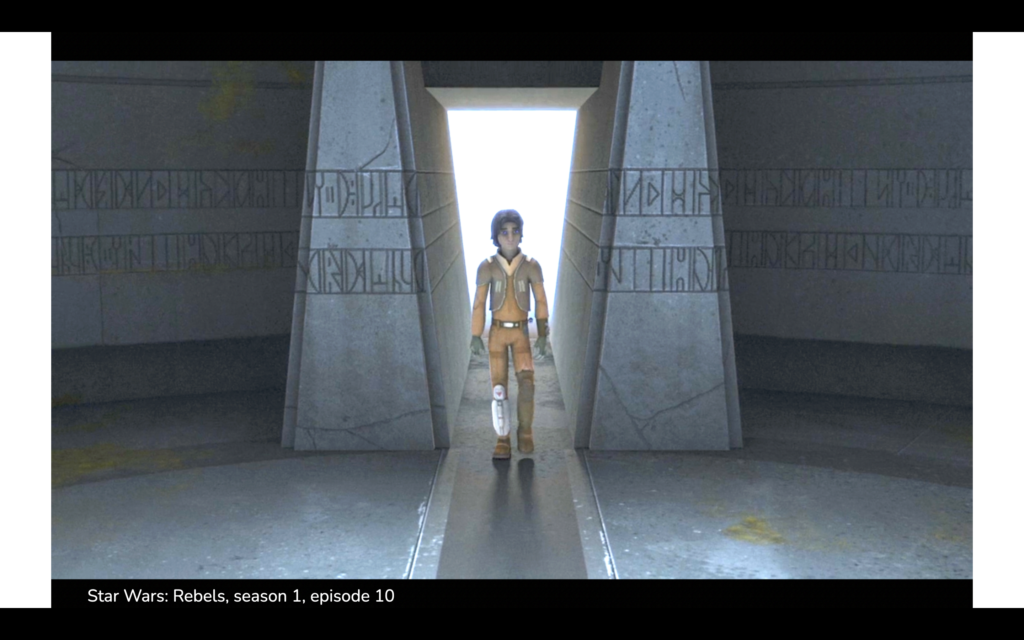

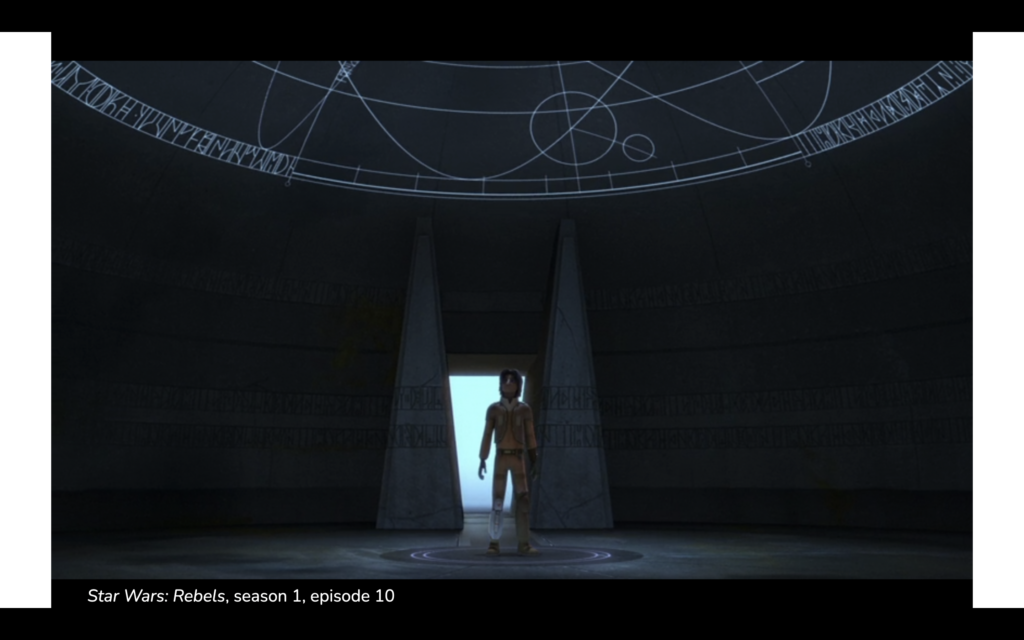

The Jedi codices aren’t the only examples of written culture that is inscribed (as opposed to digital written culture, screens and holos, which are ubiquitous in the Star Wars universe). In the Star Wars: Rebels television show, there are several times when stone inscriptions can be seen in ancient Jedi temples, such as this scene in season 1, episode 10, when Ezra Bridger first enters the temple on Lothal. I’ve lightened the image quite a bit, but you can see two parallel rows of writing that appear to line the room.

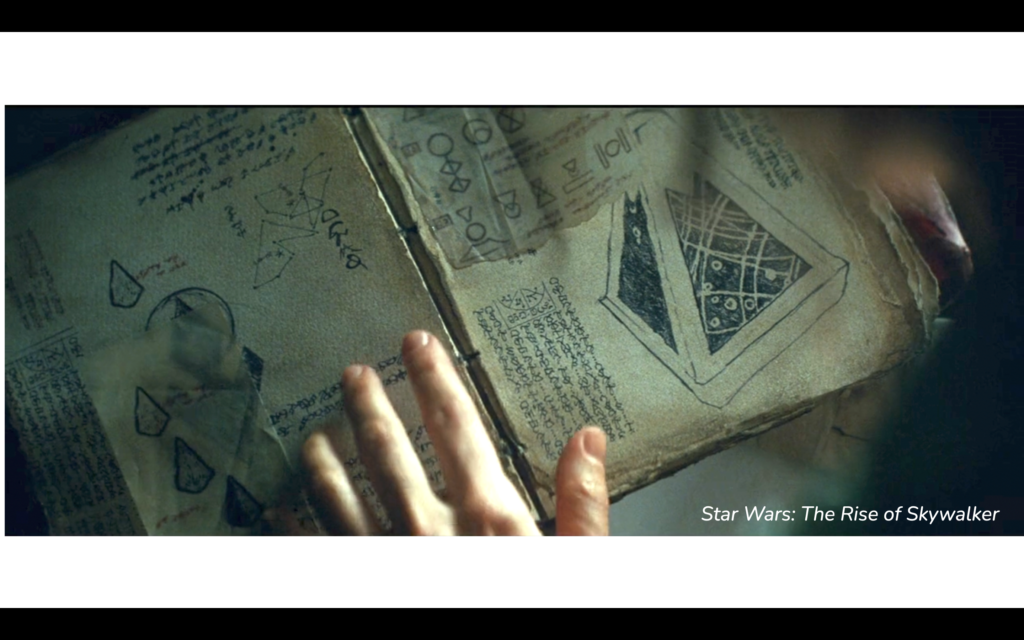

We catch another glimpse of the Jedi codices in The Rise of Skywalker, when Rey consults one of them to track down a Sith wayfinder, which will lead her to the planet Exegol.

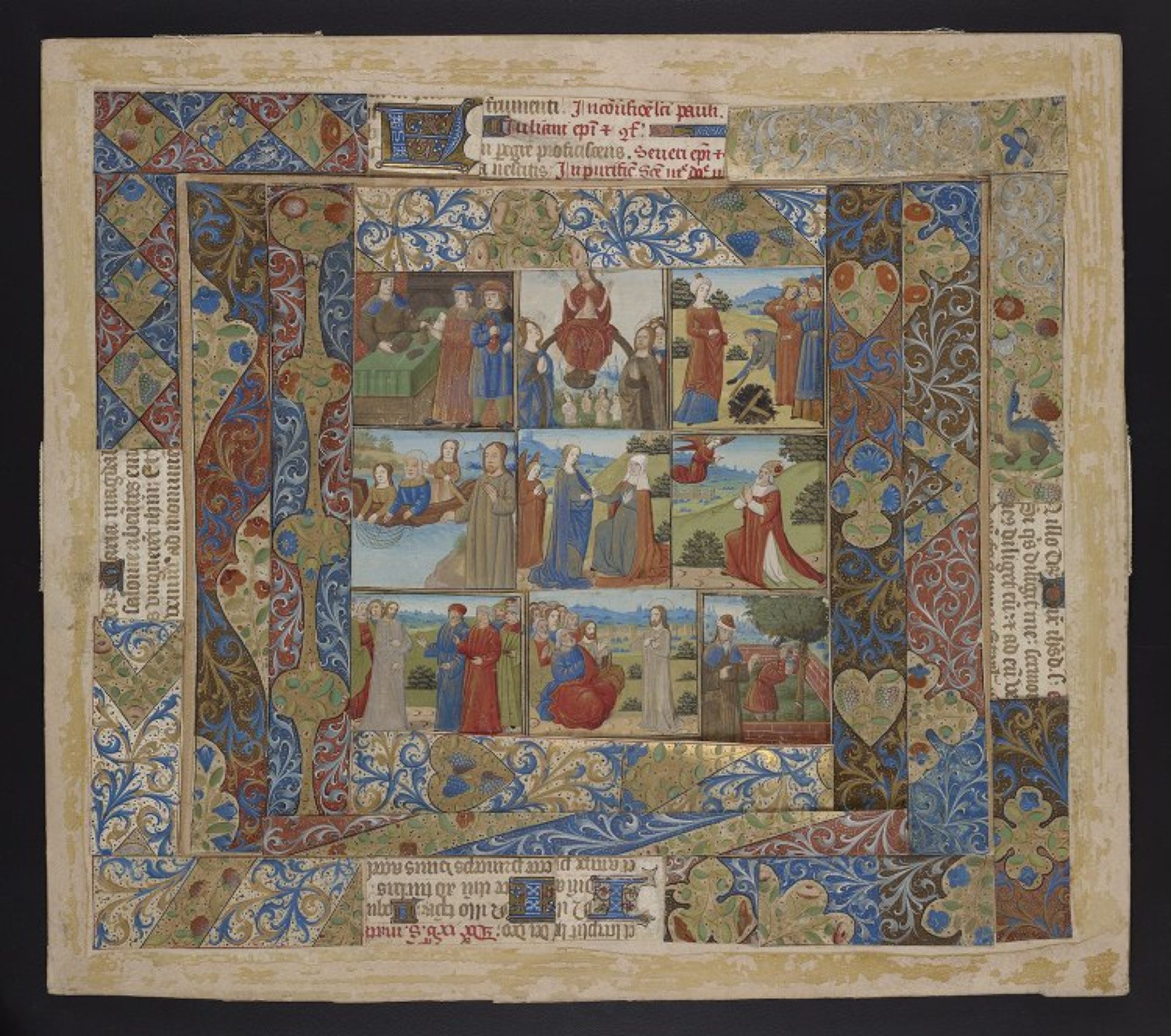

It’s unclear from the film and from the accompanying books and wikis whether this book is Luke Skywalker’s own journal, one of the original ancient texts, or something in between (that is, an ancient text with notes from him and perhaps from other people appended to them – a practice that would be familiar to many students and scholars in the middle ages).

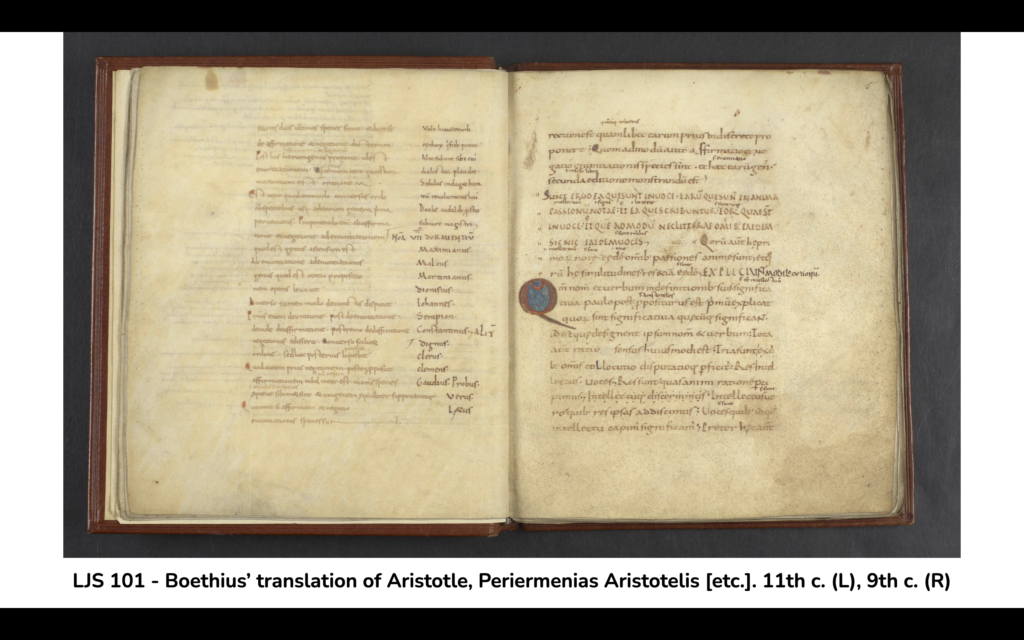

The next couple of examples are manuscripts from Penn’s collections that were created and used by multiple people. The first, LJS 101, is a Carolingian manuscript, with portions written in the 9th century and other parts written in the 11th century. It’s clear that the 11th century portions were custom written to replace sections from the earlier book, and the same hand responsible for the 11th century sections also went through the older portion and made many changes and fixes to the text there – essentially building a new book out of remnants of an old one.

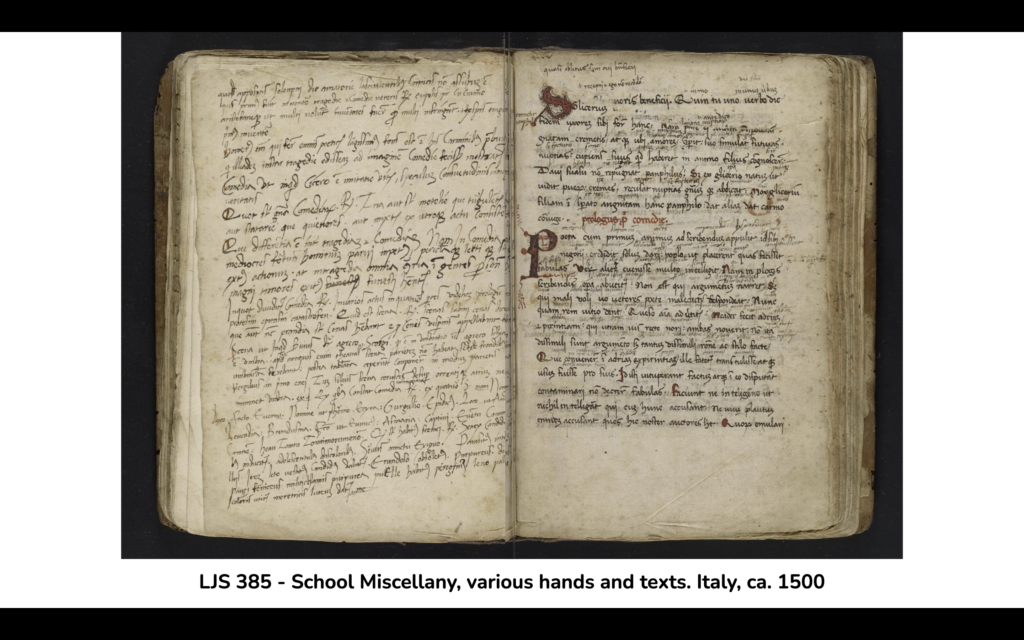

This example, LJS 385, is an early 16th century collection of school texts – Cicero, Terence, Boethius, Virgil, among others – written and with notes in a number of different hands, as you can see here. Rather than being written by different people over time, this one was written by many different people at the same time, like an early modern version of a shared Google Doc.

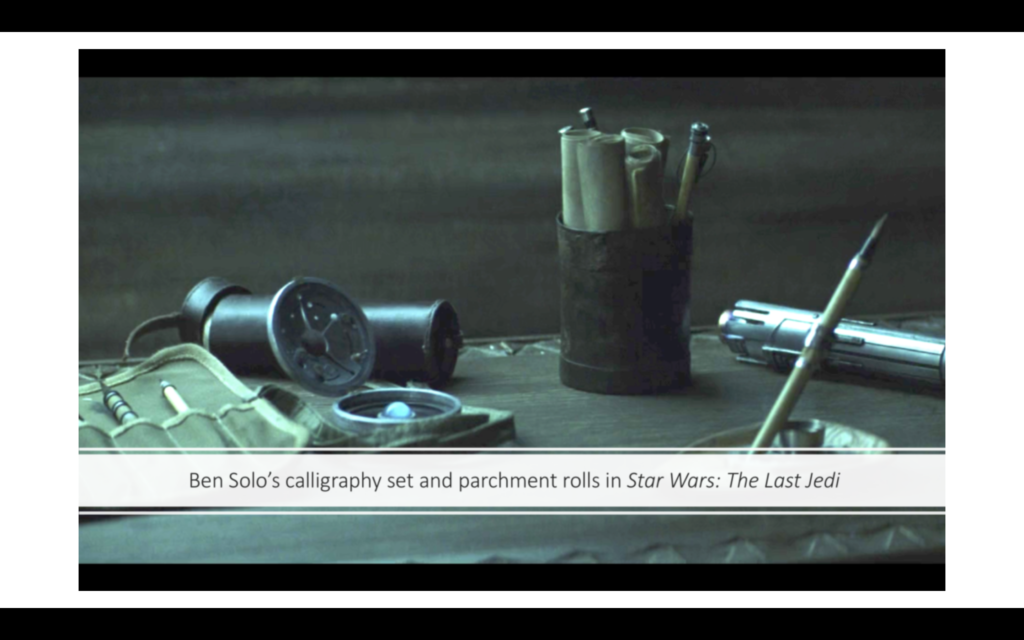

Swinging back to Star Wars canon, we know that Ben Solo, Luke Skywalker’s nephew who studied under him as a child, wrote with pens, since he had a calligraphy set in the flashbacks to his days as a Jedi student in The Last Jedi; in fact, he is the only character explicitly stated to have written on paper with pens. So it’s reasonable that his hand could be in the TROS codex, potentially along with Luke’s.

In summary, we have books on Jedi religion, history, poetics, astronomy, and other sciences, books which existed over a long period of time and which could potentially hold knowledge from multiple individuals, including characters from the most recent films. Textual culture was a major facet of the ancient Jedi religion, and the Jedi manuscripts demonstrate that the Jedi were also interested in synthesizing religion with scientific knowledge about their galaxy. As lovers of both Star Wars and medieval manuscripts, this intrigued us, since we find many of these same types of genres in premodern books.

What types of manuscript codices do we know that contain parallels? In our previous work, we have explored specific manuscripts in the Schoenberg Institute at the University of Pennsylvania that share certain similarities. Our next few slides will illustrate some of these aesthetic comparisons.

Science and Spirituality

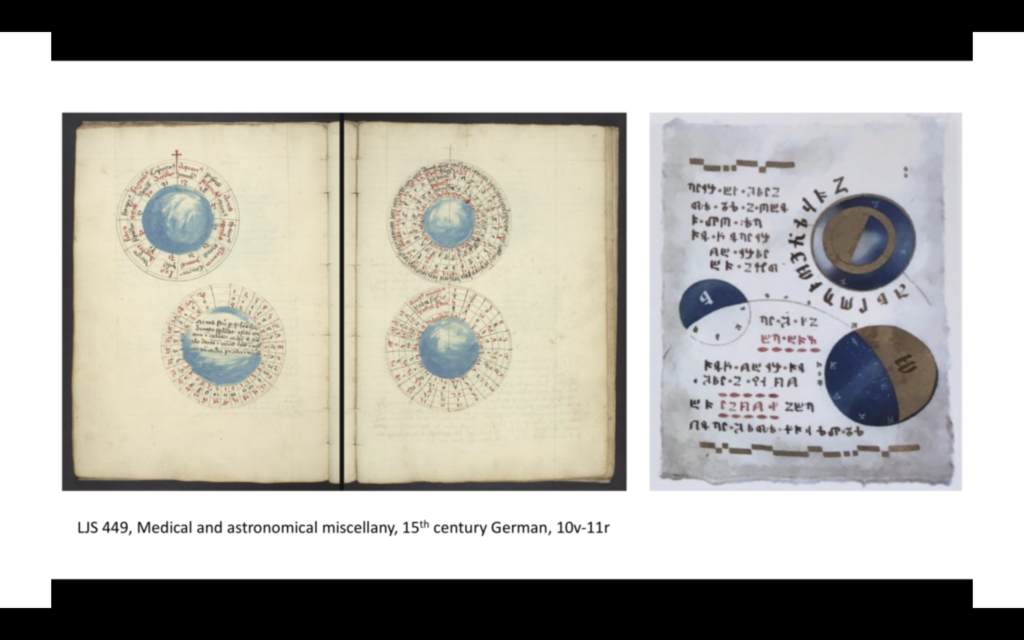

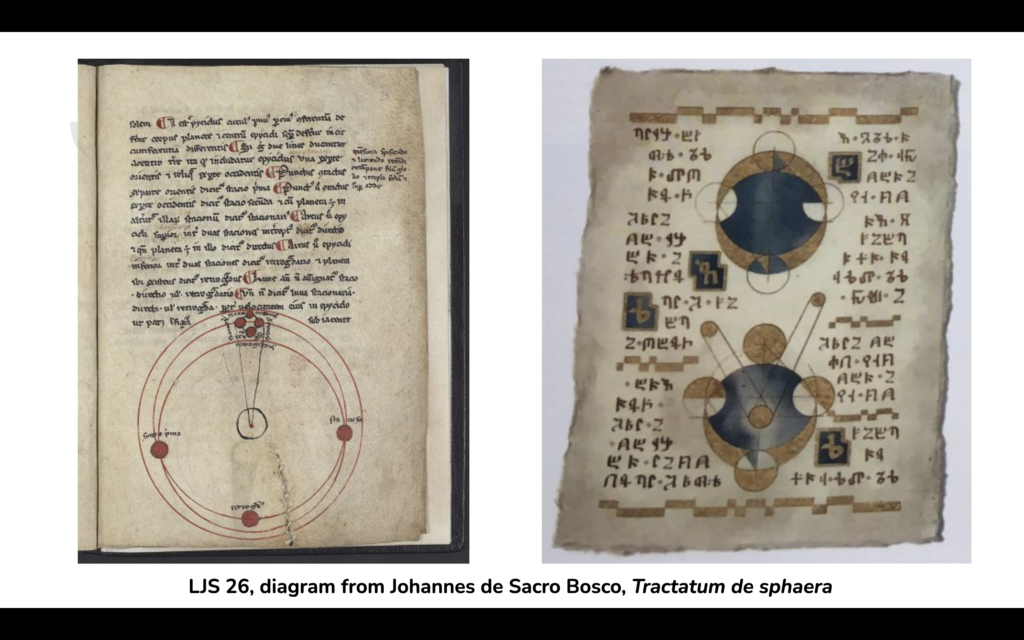

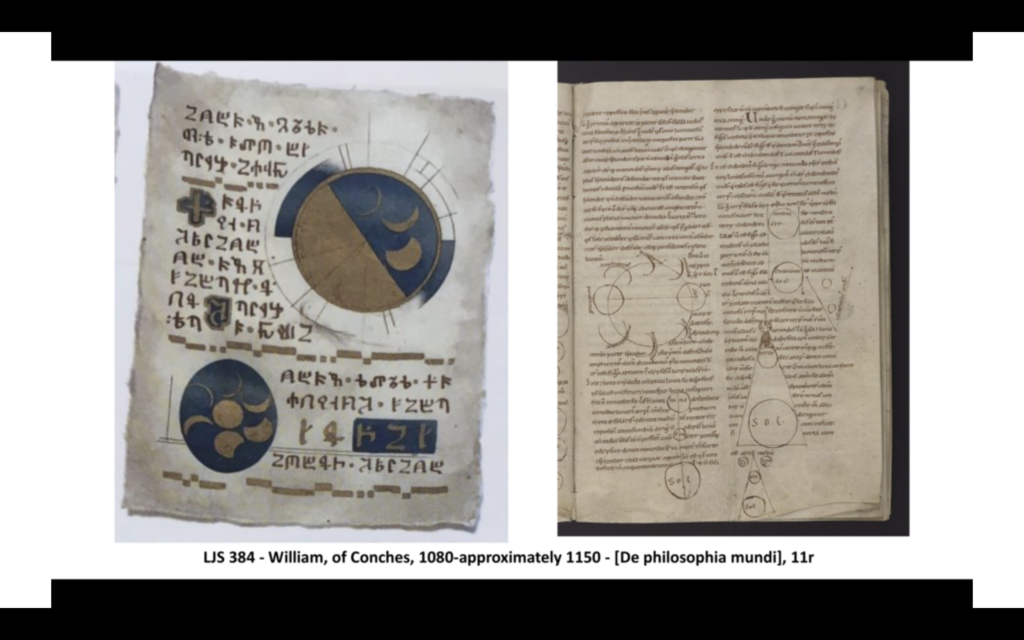

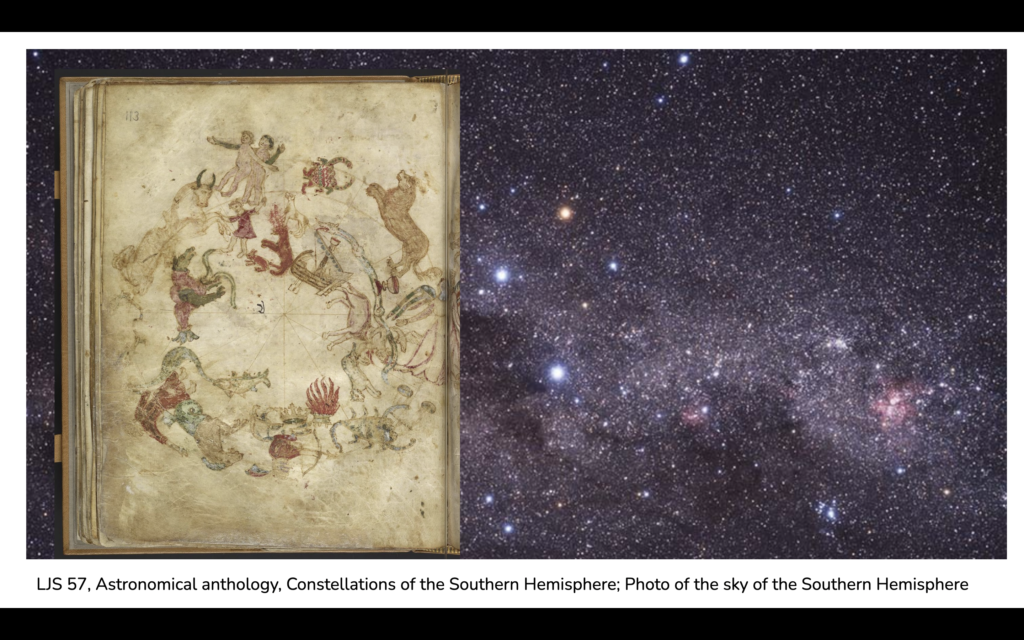

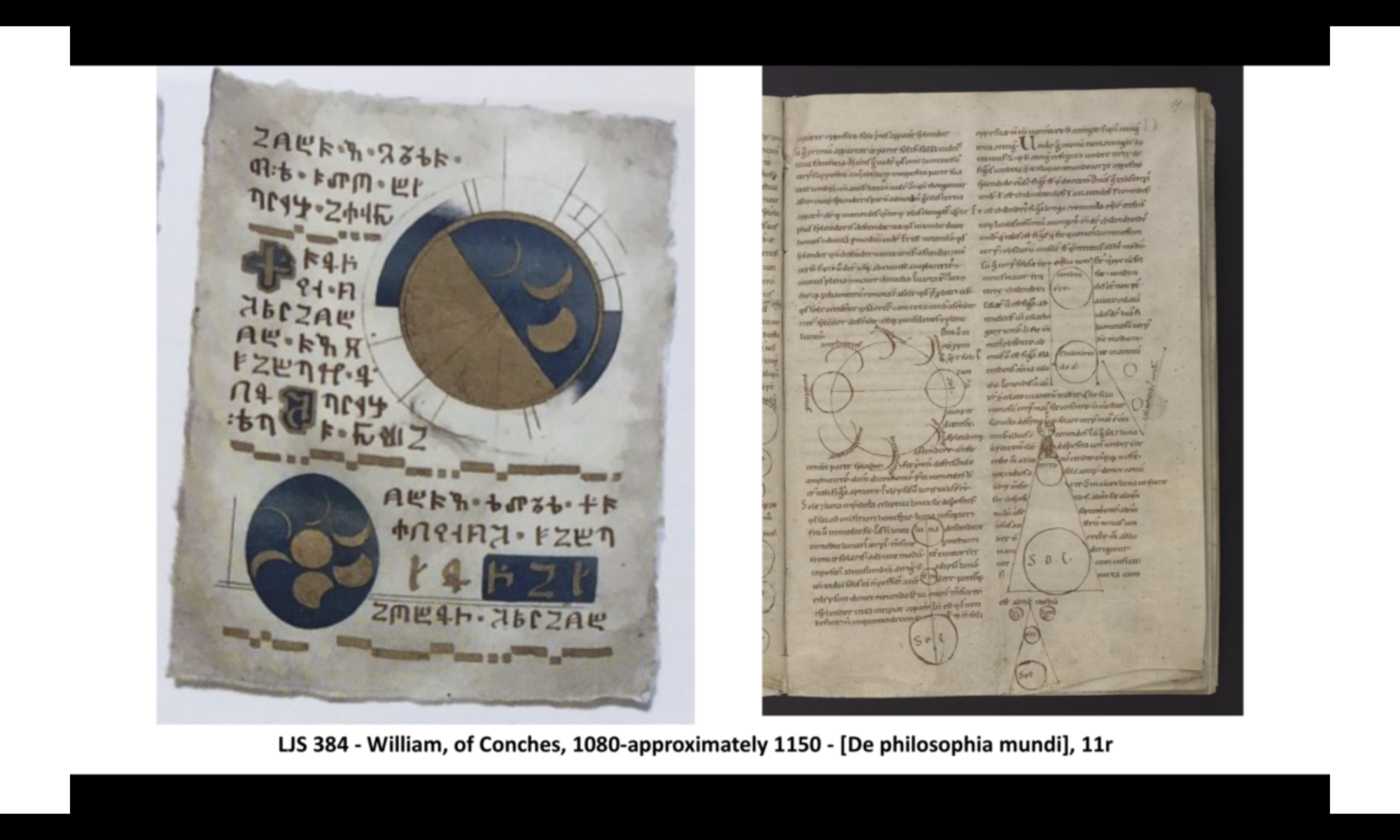

It’s especially worth considering connections between scientific and more mystical approaches that we see combined in the manuscripts (medieval and Jedi). For example, medieval and Jedi manuscripts seem to evoke the idea that astronomy helps people to consider their place in a wider cosmos infused with spiritual existence, whether that’s Christianity, Islam, or the Force. It’s worth remembering that all of this knowledge–in Star Wars and our world–is composite, accumulative, synthetic, over centuries of time.

For example, we might consider astronomical works by someone like the thirteenth-century author John of Sacrobosco. This type of medieval astronomy is built on classical knowledge, and authors in both East and West pursued their own views variously through the lenses of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. In the later Middle Ages, as Europeans engaged more with Islamic texts, all of these became synthesized; so we find an accumulation of science, religion, philosophy, and other approaches being woven together. Similarly, the Jedi texts, like Luke’s notebook, are also composite, pulled from hundreds or thousands of years of scientific, religious, and philosophical views by different authors and in multiple languages across the galaxy.

They all use drawings – which are limiting – to describe something that’s really hard to describe at all. Medieval astronomers only had to think about the earth, and the moon, and the sun, and a few other planets. On the other hand, the Star Wars universe operates on a whole other level – a galaxy with countless star systems and planets that aren’t even charted. When I look at these diagrams I see a clever attempt to illustrate scale using the relatively primitive technology of ink and paper in place of the star charts and 3D maps that we see in the films.

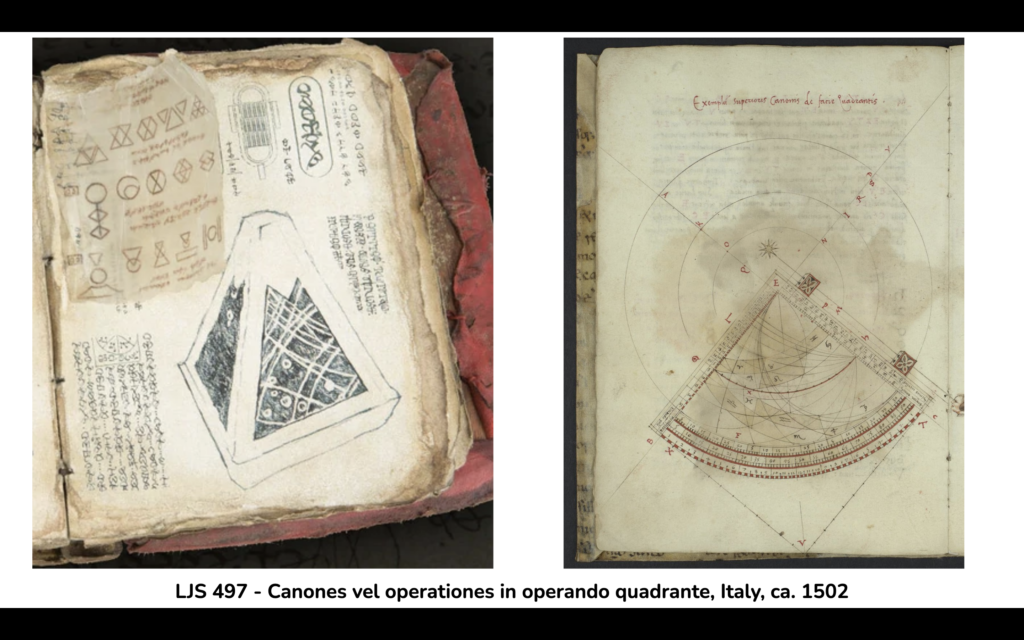

In a related way, the wayfinder in the Jedi book from The Rise of Skywalker is similar to diagrams about astrolabes that we see in medieval manuscripts, like LJS 497, which is an illustrated treatise on the use of the astrolabe quadrant, pictured here. Both the wayfinder and the astrolabe quadrant are tools that act as technologies of astronomical knowledge: objects in the real world that are described, as well as possible, in books.

What’s intriguing about all of this is that medieval thinkers, and presumably the Jedi, were trying to account for both textual and visual explanations, in order to use multiple media to get at deeper, more sophisticated meanings. And a part of that is navigating between abstract knowledge in books and application in the material world around them.

World Between Worlds

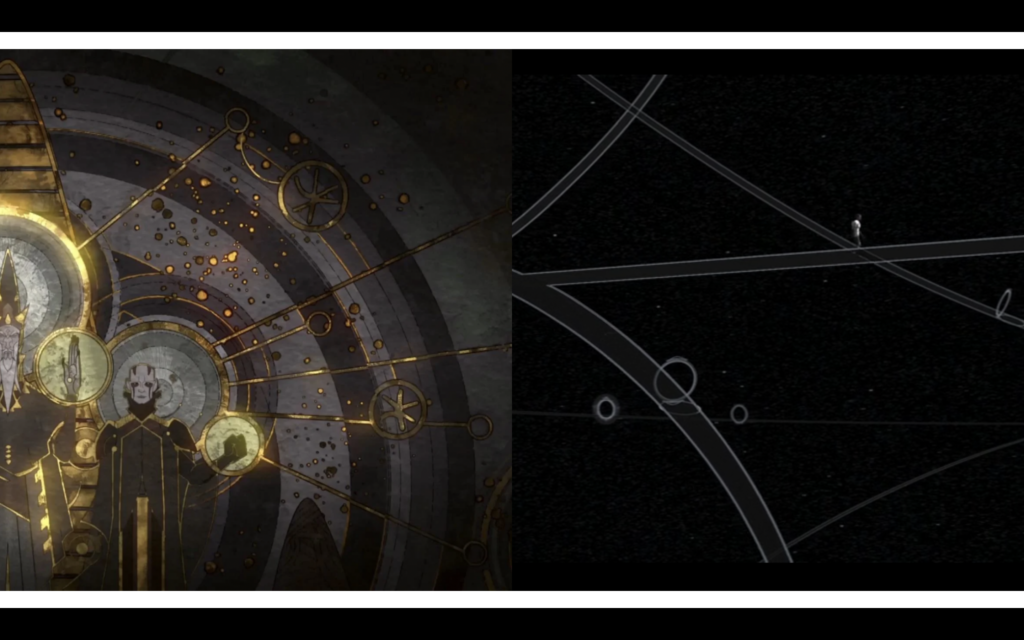

We can draw parallels between the charts in the manuscripts in The Last Jedi to medieval astronomical manuscripts; but in The Rise of Skywalker and the Star Wars: Rebels television show we learn of a new concept, which complicates the simplicity of these parallels: the World Between Worlds. According to Wookieepedia, the World Between Worlds is “a mystical plane within the Force that served as a collection of doors and pathways existing between time and space, linking all moments in time together.” Some of the illustrations that we’ve pegged as astronomical (and which are clearly influenced by astronomical illustrations from our world) are, we think, more generally about various worlds interconnecting. The designing artists for the Jedi manuscripts, then, used medieval astronomy diagrams as the basis for showing the World Between Worlds.

In the Rebels TV show, we see this play out as Ezra visits the various Jedi temples and eventually enters the World Between Worlds. This screenshot is taken slightly later in the same episode we saw earlier, in the same room – not only do we have more writing, but we have our first glimpse of a representation of the pathways of the World Between Worlds.

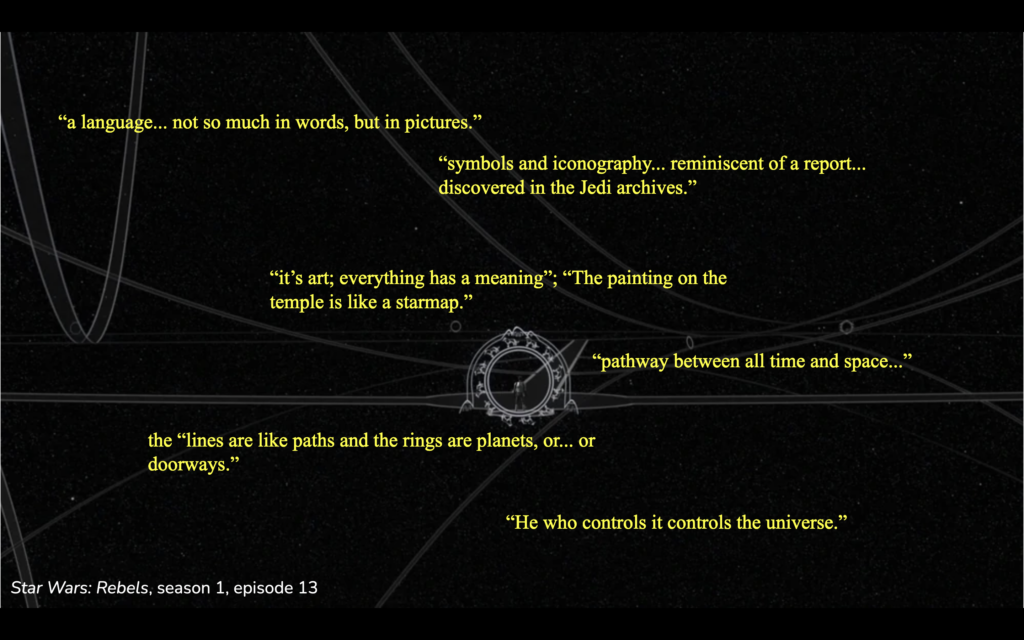

In the World Between Worlds, we find a synthesis of space-time religion. In the episode titled “Wolves and a Door” (season 4, epsiode 12), the rebel protagonists visit a Jedi temple and find artifacts decorated with what they describe as “a language… not so much in words, but in pictures.” Later, a character named Hyden (the overseer of the imperial operation at the Temple) describes the decorations as “symbols and iconography… reminiscent of a report… discovered in the Jedi archives.” Sabine Wren says, “it’s art; everything has a meaning”; and “The painting on the temple is like a starmap.” She continues, the “lines are like paths and the rings are planets, or… or doorways.” What becomes clear is that these symbols are key to opening a gateway. In the following episode, titled “A World Between Worlds” (season 4, episode 13), Hyden calls the gateway in the temple a “pathway between all time and space” and goes on, “He who controls it controls the universe.”

The “World between Worlds” idea is about time & space being bound up: the portals are for traveling not only between planets but also between times. So we see that Jedi religion and science meet in a mystical representation of space-time not unlike the treatises that meditate upon religion and science from medieval culture.

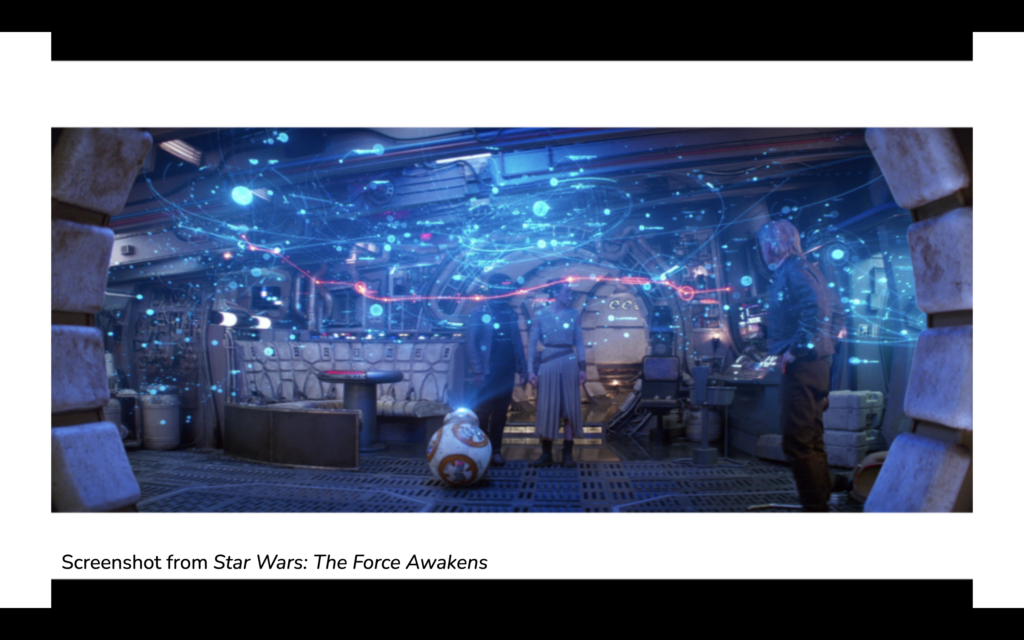

We would be remiss if we didn’t show a comparison between the Jedi artist’s conception of the World Between Worlds and how the place appears in the show’s real life. Here is what is effectively the key to the doorway leading to the world between worlds, with the gold lines representing the paths and the circles representing doorways.

It’s much brighter and more artistic than the place that the characters find themselves in – in a similar way,

medieval diagrams of the celestial spheres and constellations present a standardized and at times artistic version of what they would see in their own sky at night.

Conclusion

There are obviously many other connections to textual culture in Star Wars; myriad Star Wars media feature other objects with text or wider associations with reading, writing, and communication. In addition, there are other examples of cultural heritage objects present, at times in very important ways, in the various Star Wars properties. For example in Star Wars Rebels, there’s Hera’s Kalikori, a family heirloom passed down from family generation to generation only to be stolen by Grand Admiral Thrawn, and we also see Drydan Vos’s personal museum in Solo: A Star Wars Story. The way these objects are contextualized reflect our own world in interesting ways; they’re reflections of the past, objects to be used, treasures to be kept safe, things to be owned. The issues of who owns them, and who benefits from them will be familiar to anyone who has kept up with recent news stories regarding repatriation of objects from the Green Collection and other institutions. This takes us far beyond manuscripts but, we hope that what we’ve presented here are just starting points for future work on these and related subjects.

EDITING this on December 1, 2024, to add something from a comment on another one of my posts back on October 4. There’s another manuscript that appears in The Rise Of Skywalker Visual Dictionary (which we didn’t look at) which is a direct copy-and-paste from a manuscript of kitab al-tafhim by al-Biruni (Library, Museum and Document Center of Iran Parliament, Ms. 6565). I found this image on WikiMedia, and I’m guessing that’s where they found it. That’s just lazy! Please don’t be lazy! Use manuscript art for inspiration, don’t copy it. (Something something, unsurprising given how lazy the rest of TROS is, something something).

One Reply to “Aionomica, Rammahgon, and De sphaera mundi: Bibliographic Medievalism in Star Wars”