This paper was originally presented at the International Medieval Congress in Leeds, UK, in July 2025. It was part of the session In Memoriam Johanna Green, III: Digital Medievalisms and owes a huge debt to Johanna Green, who was a great scholar and a great friend.

Thank you to Christine and Colleen for organizing these sessions and for accepting my paper. I’m excited to talk with you about a project that I’ve been working on for a while, one that was very much inspired by Joanna.

I want to begin by saying a few words about her. I first met Joanna online—I’m not sure exactly when—but I remember clearly meeting her in person at Kalamazoo in 2018, when she organized a series of Digital Skin sessions. I presented alongside her and Bridget Whearty on Saturday, May 12, 2018, at 3:30 PM—so it’s fun to be able to date that precisely. The work we did together, and the conversations that followed, were deeply formative for this project and others.

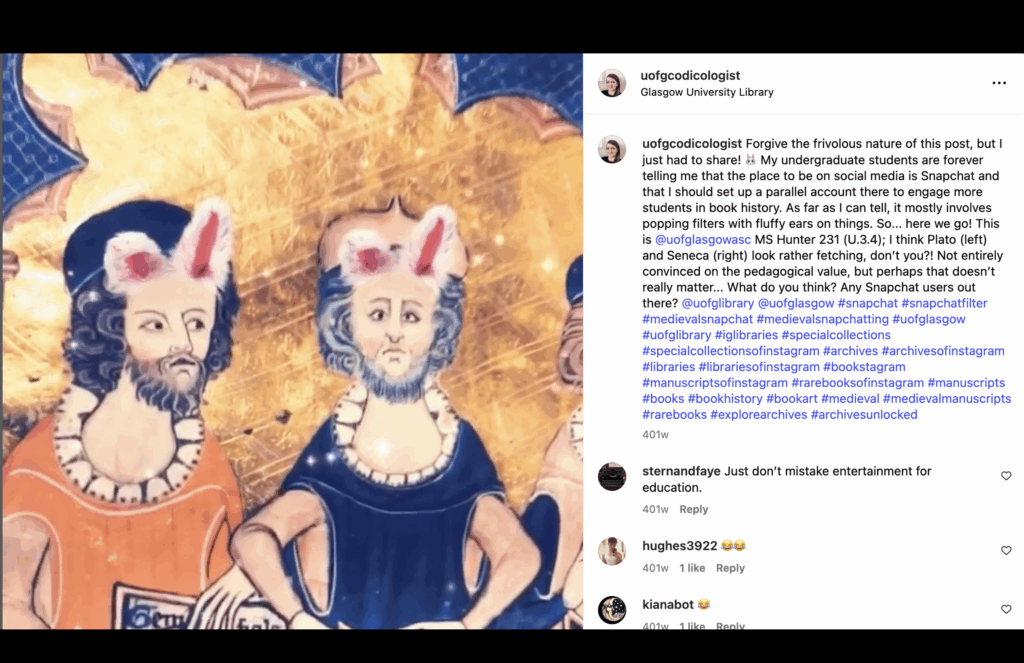

Everyone has talked about how brilliant and supportive Joanna was—and she truly was—but she was also so much fun. When I think of her, I smile. She was funny, creative, deeply thoughtful, and passionate about the materiality of manuscripts—especially what happens to materiality when manuscripts are made digital.

A screenshot from Johanna’s Instagram account

I’m sure many of you have read her article Digital Manuscripts as Sites of Touch: Using Social Media for “Hands-On” Engagement with Medieval Manuscript Materiality (Archive Journal, September 2018). I found this quote particularly meaningful, both for this talk and in general:

“The content and codex of a manuscript are materialized by interaction with a technological platform: the text is materialized by the technology of the codex; the physical codex is materialized when it is manipulated by the hand; the digital image is materialized when it is called on screen and touched by the audience’s fingertips. All are connected to one another because all must be “materialized” by interaction with the technological platform, interaction made manifest by the hand. They are made “real” because they are experienced.”

– Johanna Green, “Digital Manuscripts as Sites of Touch: Using Social Media for “Hands-On” Engagement with Medieval Manuscript Materiality” Archive Journal, 2018

In other words, interaction—physical or digital—is a key part of a manuscript’s materiality

Much of what I’ll show today is inspired by various projects and collaborations. I won’t go into detail on all of them because of time, but I’m happy to talk about any of them afterward.

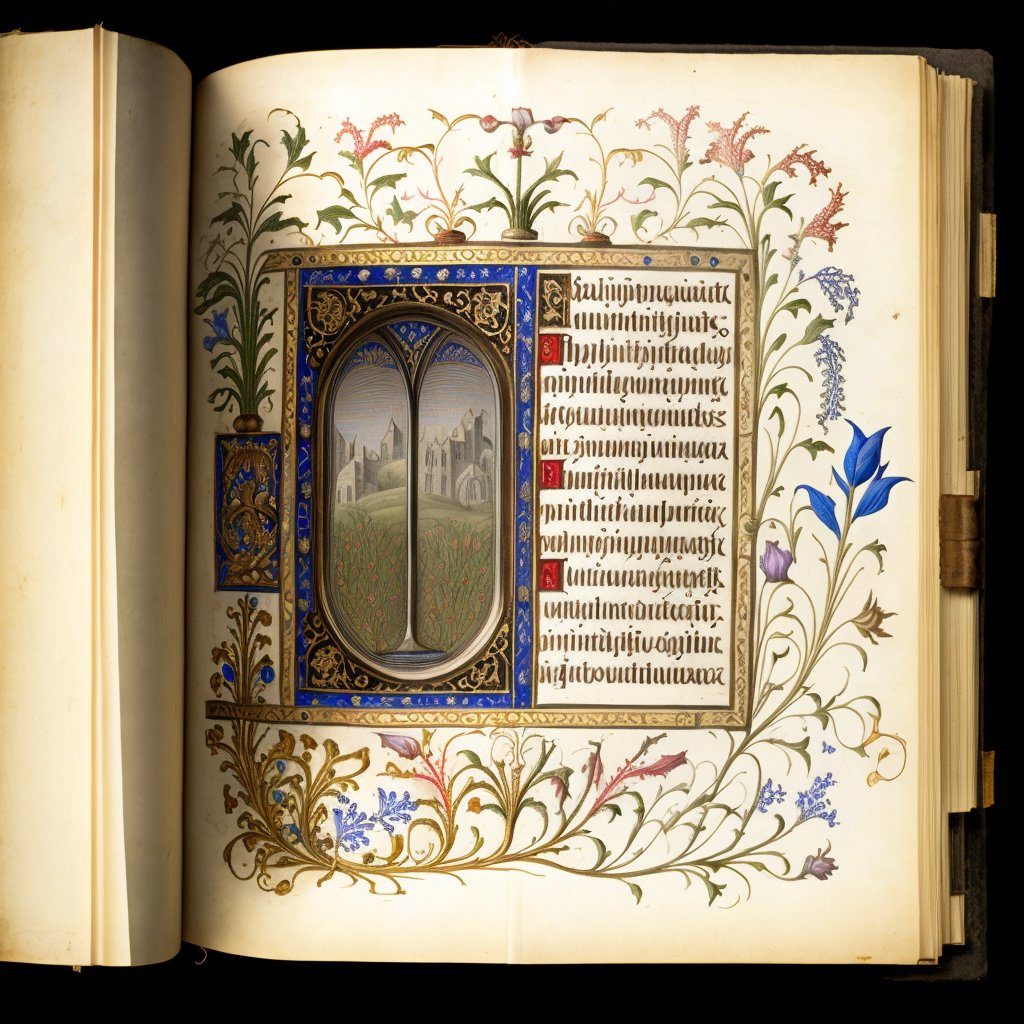

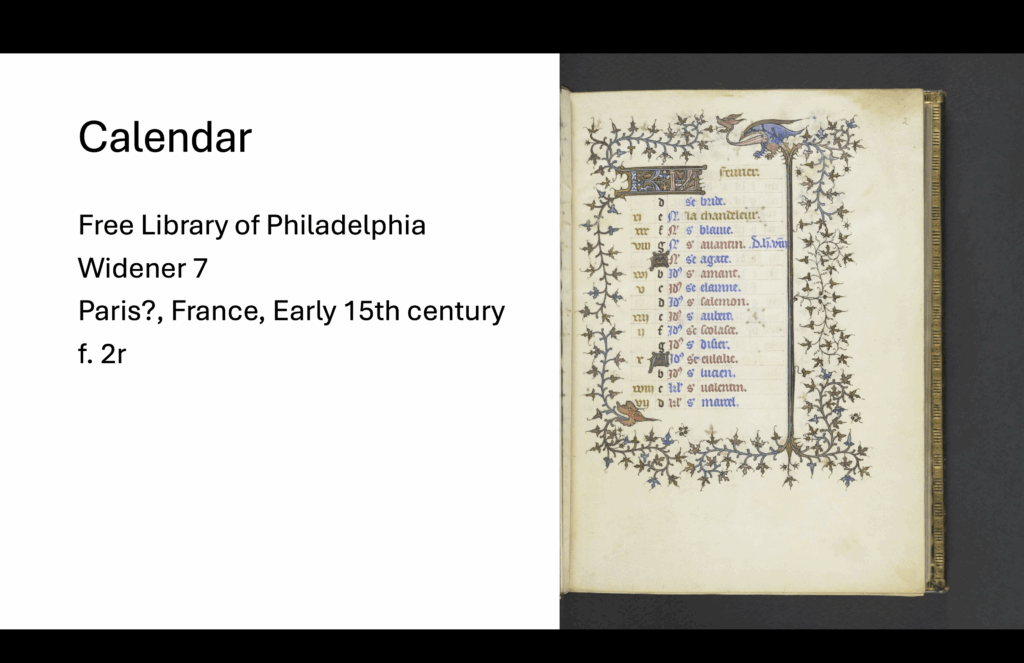

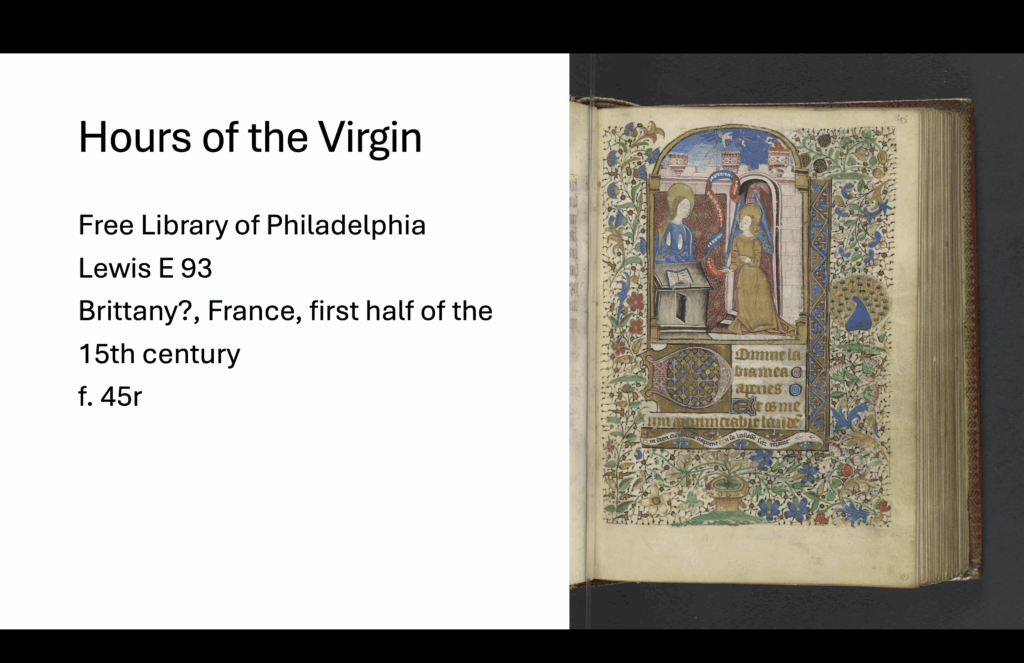

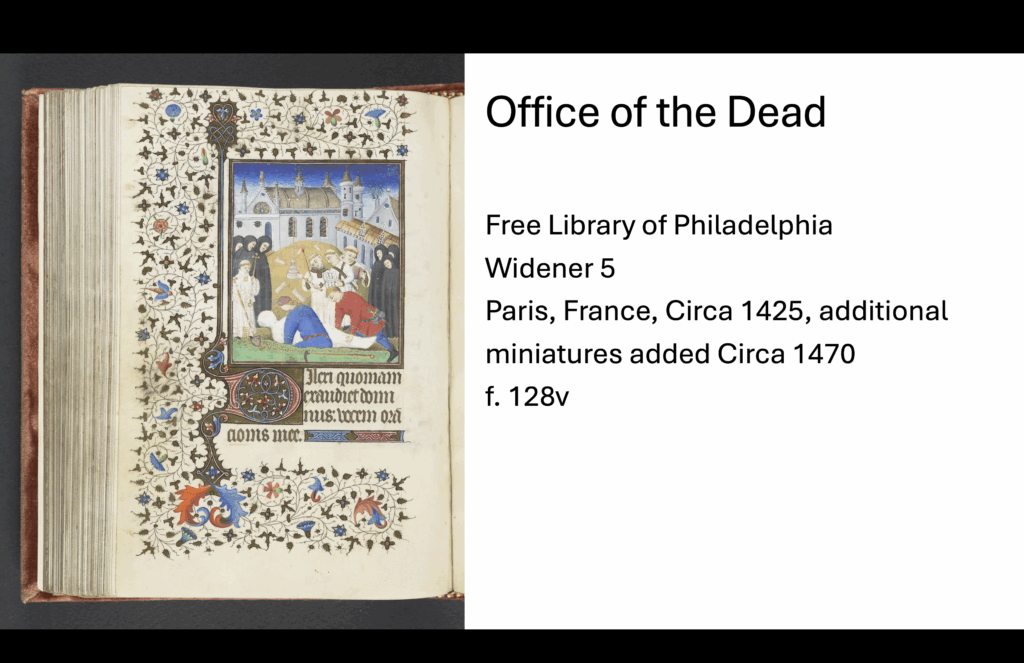

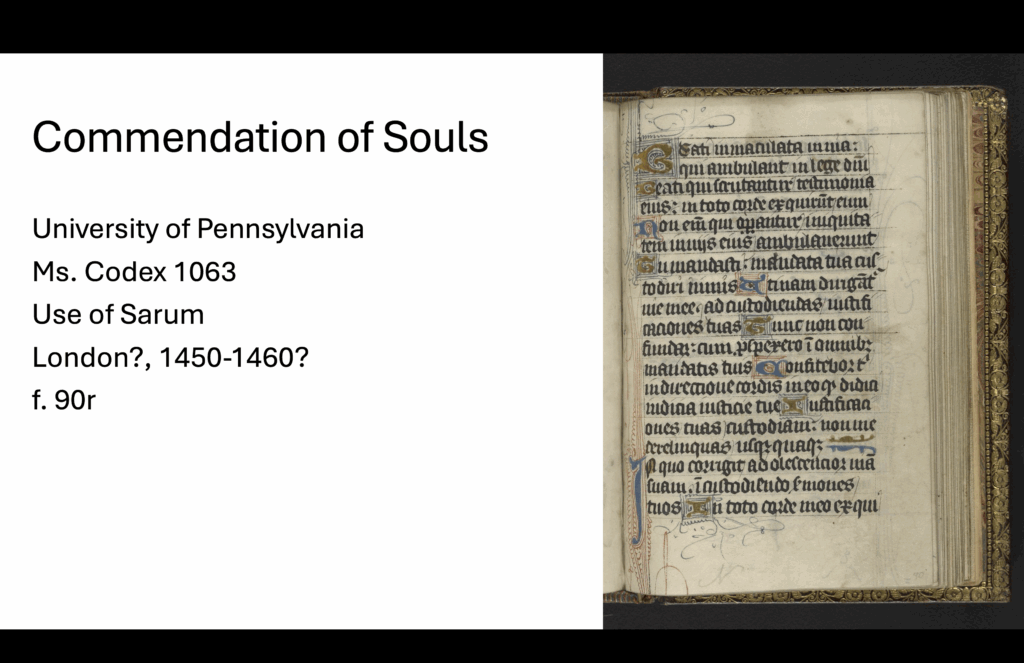

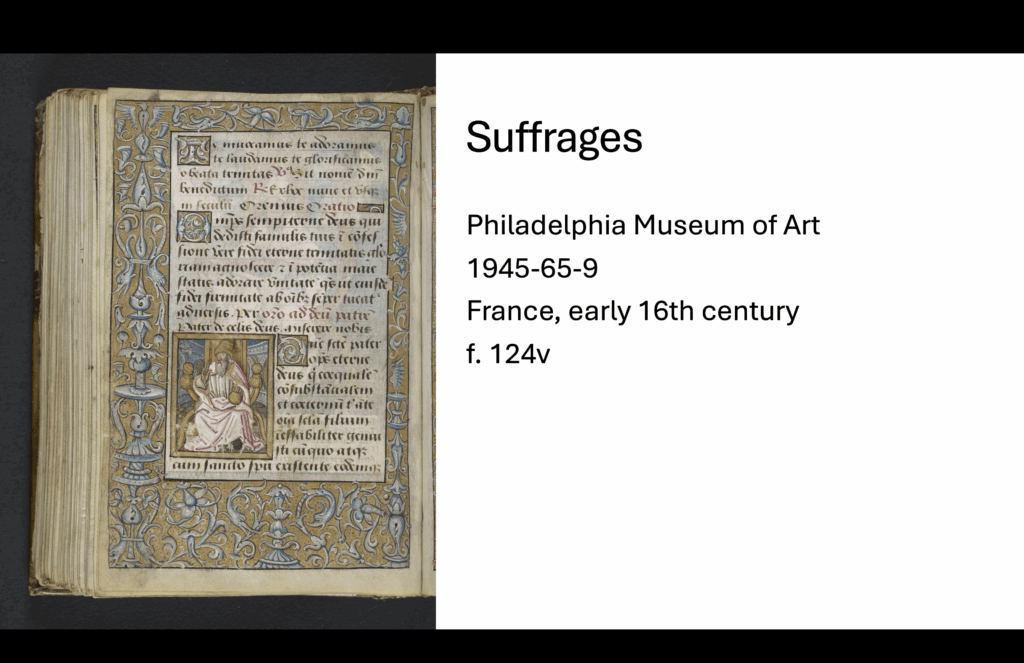

One major influence is Bibliotheca Philadelphiensis (or BiblioPhilly), a Council on Library and Information Resources–funded project that digitized around 475 codex manuscripts from across Philadelphia, including a large number of Books of Hours. We not only photographed the manuscripts, but also created collation models for many of them. If you’re unfamiliar with collation models, I’ll explain them briefly in a moment.

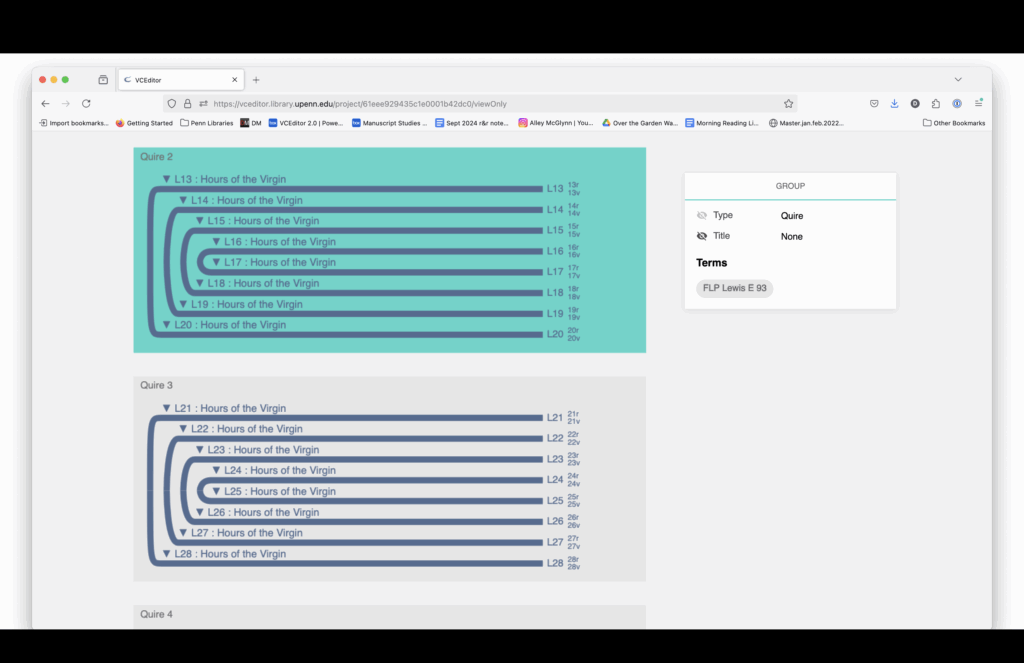

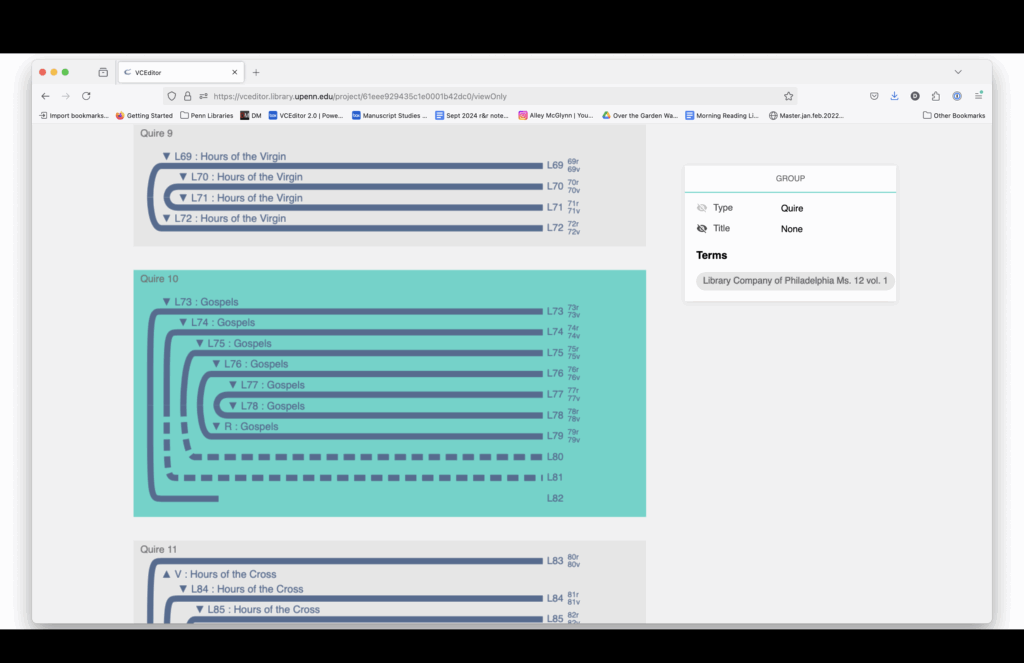

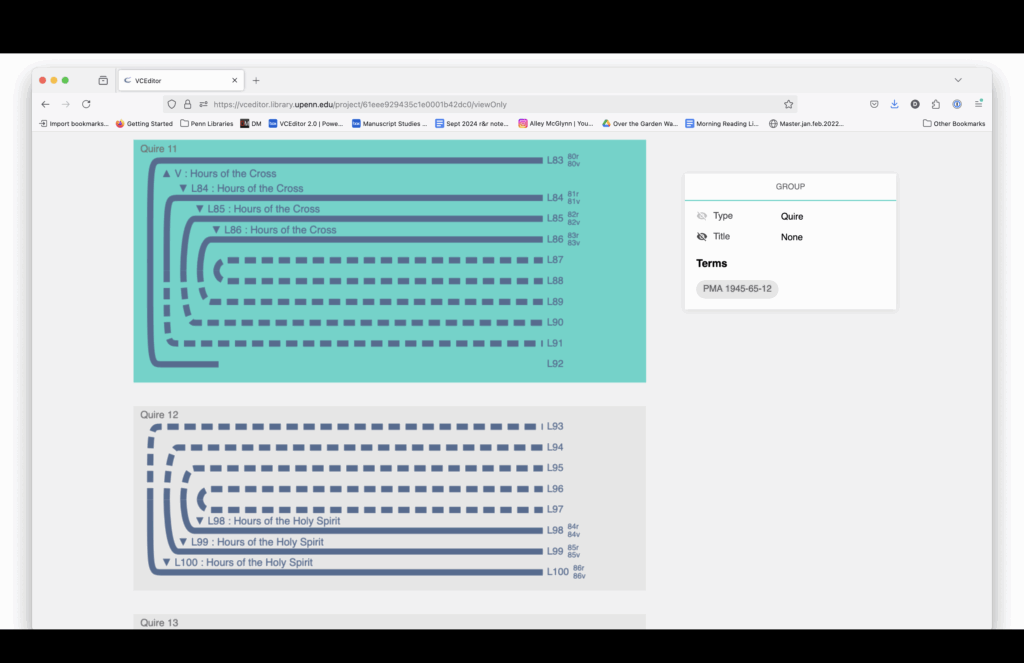

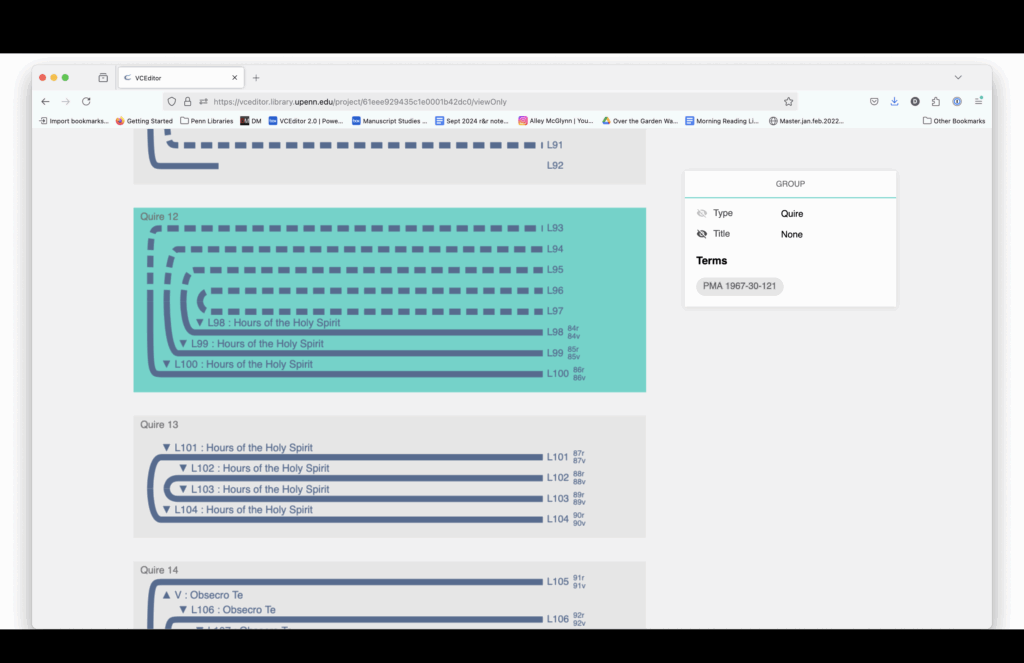

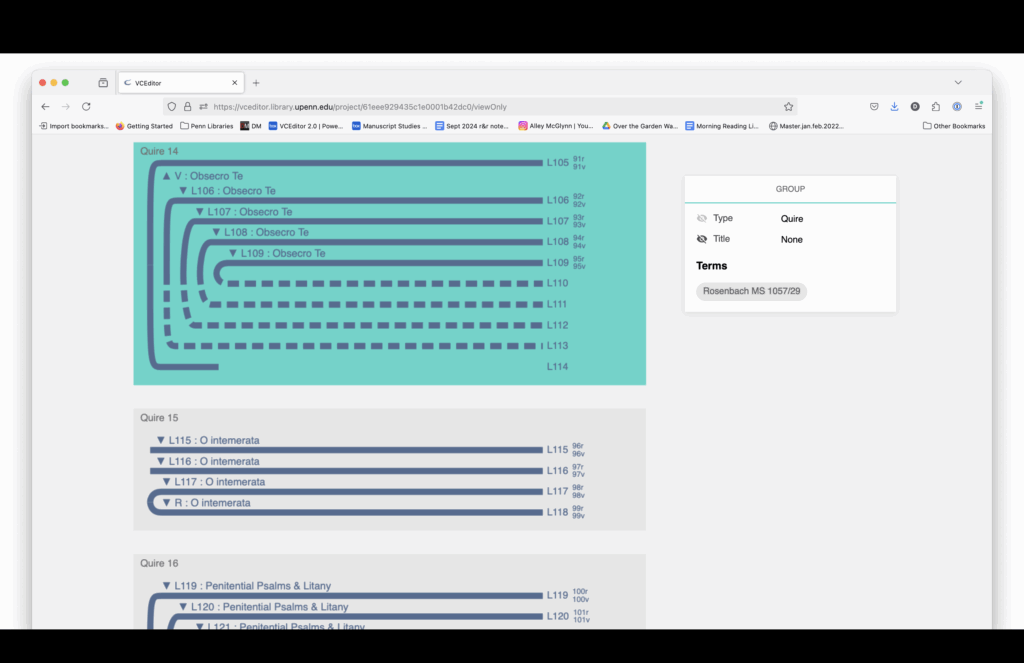

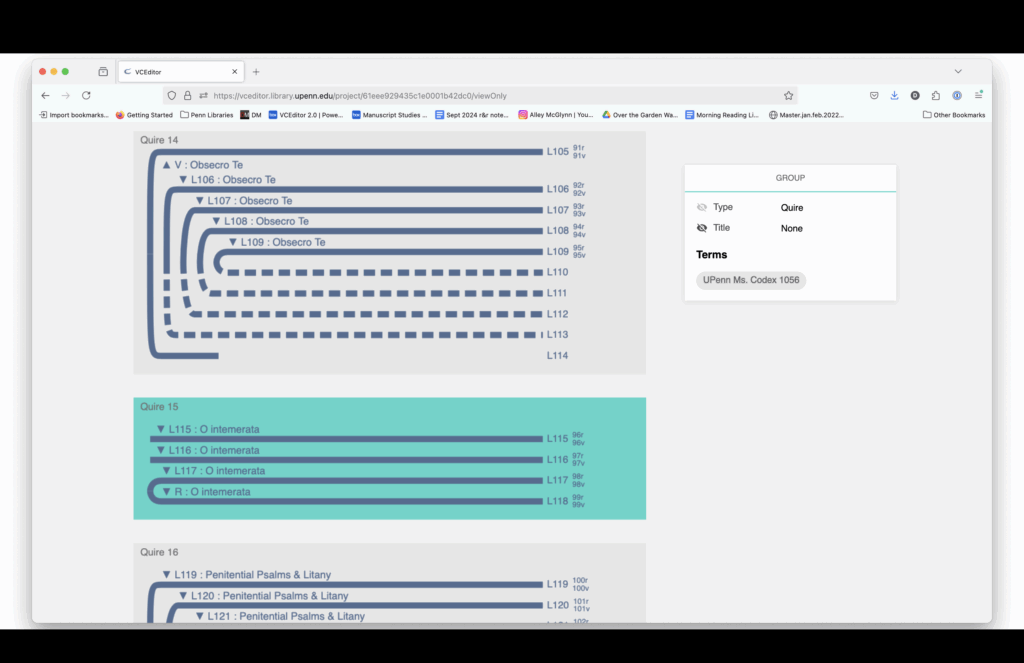

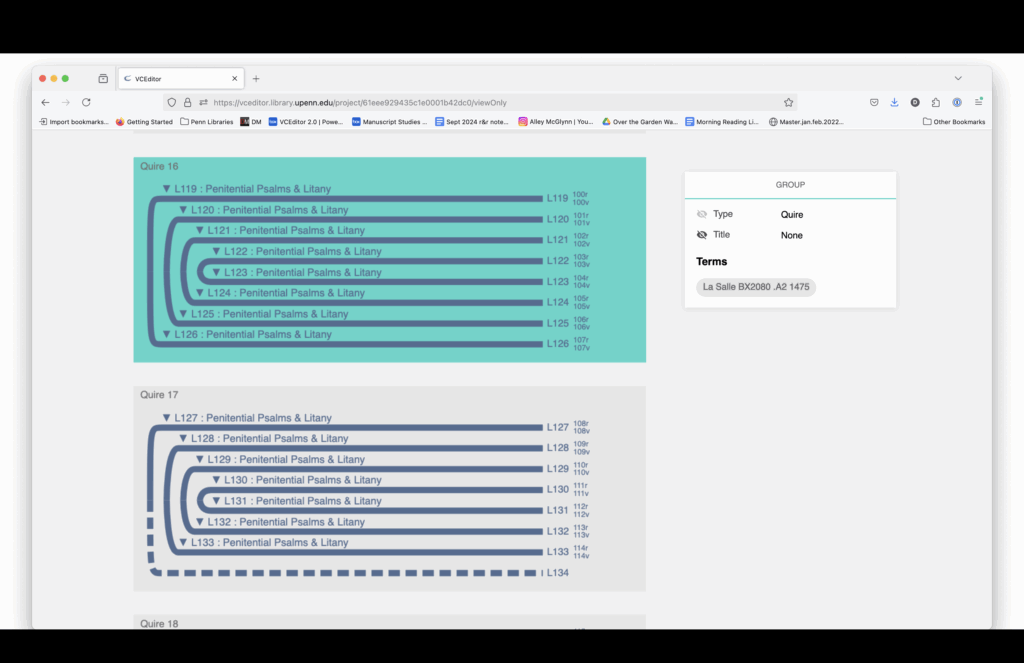

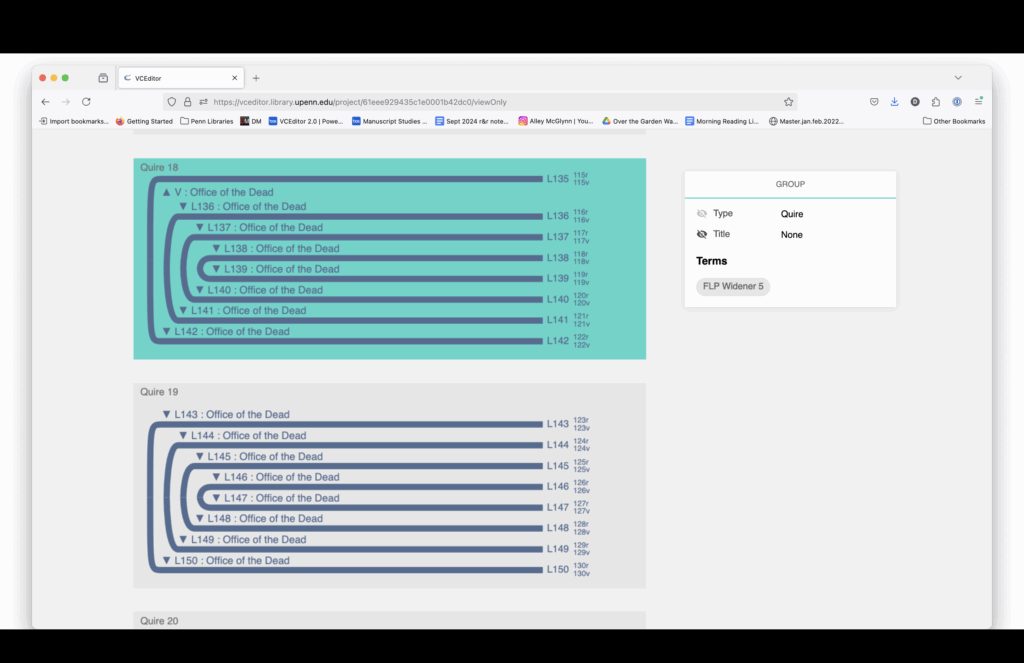

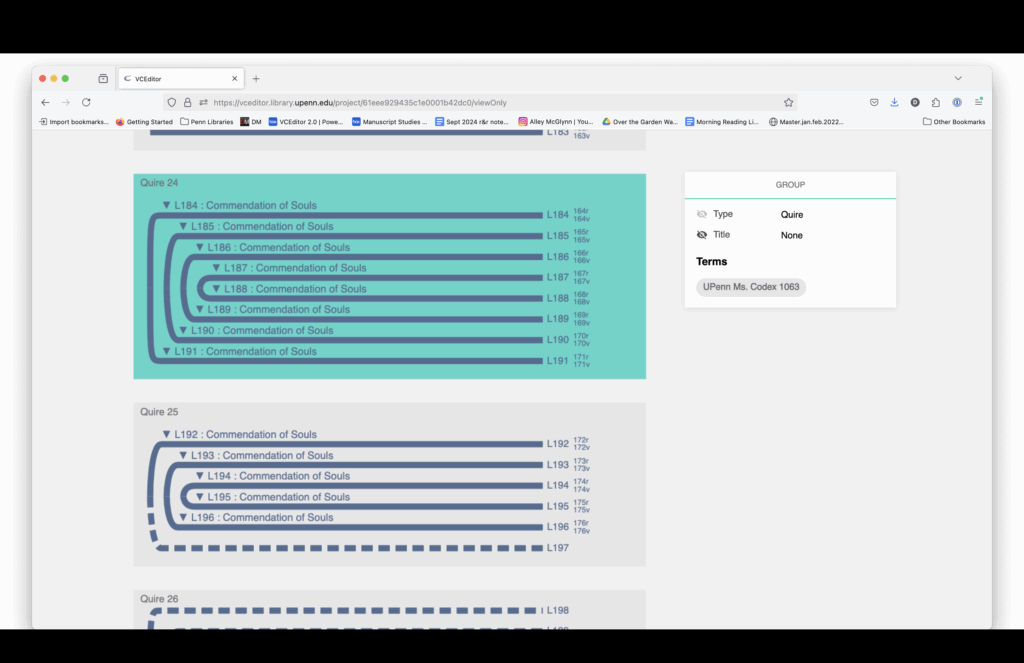

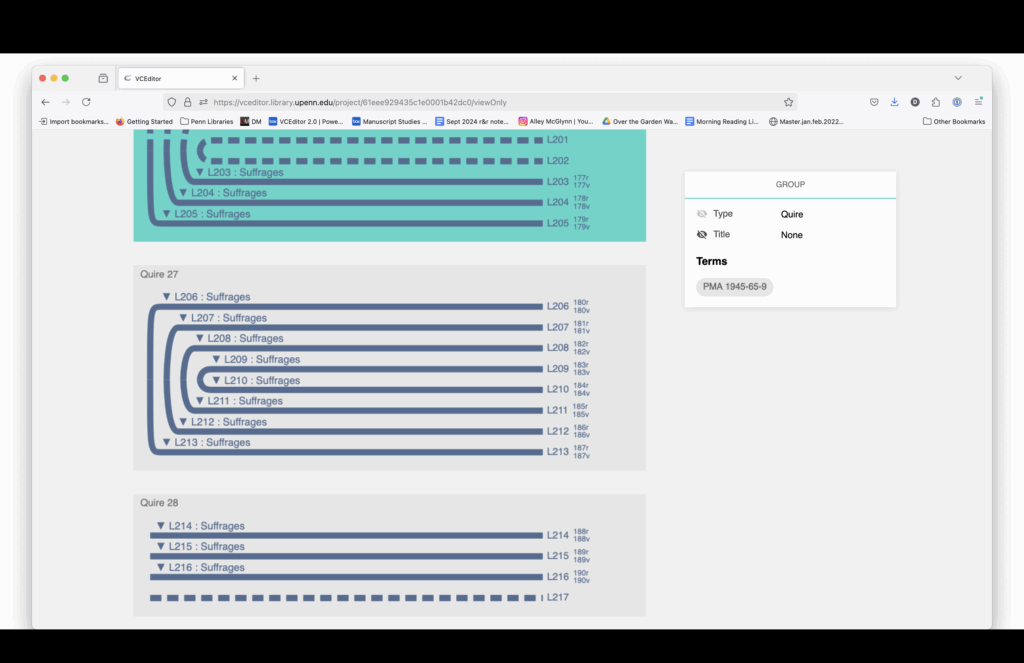

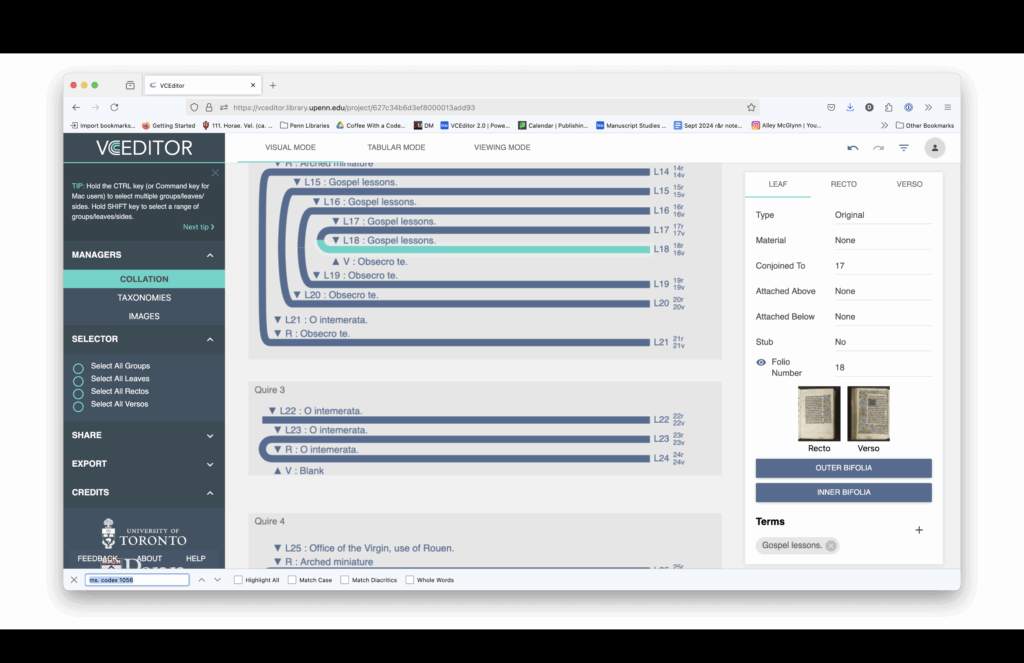

I co-direct the VisColl Project with Alberto Campagnolo. It began on July 26, 2013, when I sent a message to the TEI listserv asking if anyone wanted to collaborate—and Alberto replied. We’ve been working together since. Essentially, we’ve developed a software tool and data model for creating structural models of manuscripts and mapping their contents.

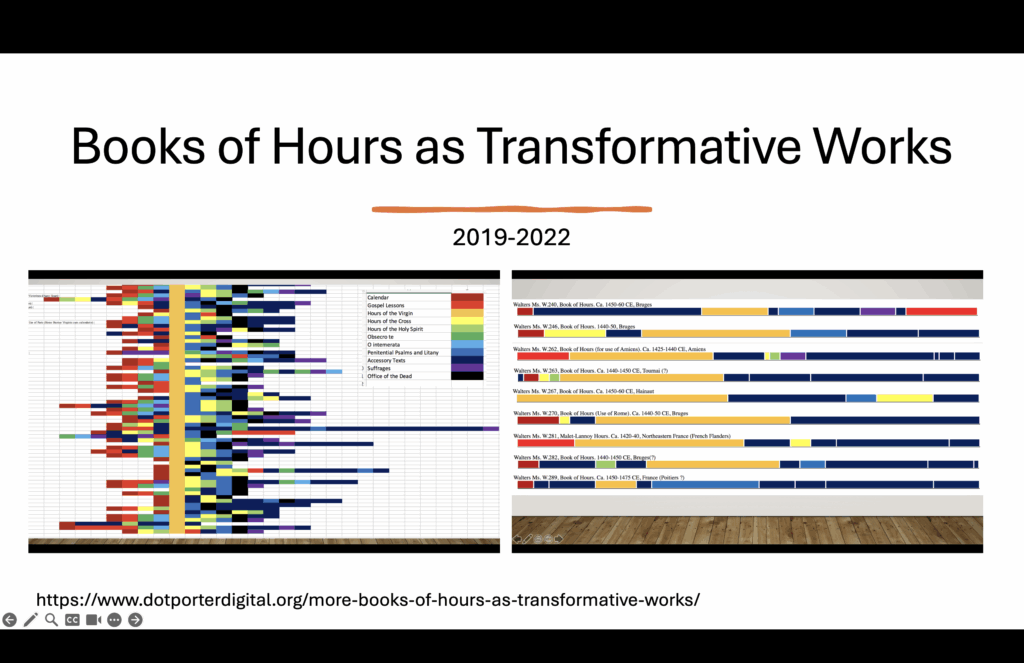

Between 2019 and 2022, I also worked on a project called Books of Hours as Transformative Works. If you’re not familiar with the term “transformative work,” it comes out of fandom studies—think of fan fiction or fan art—where people respond emotionally and creatively to something they love. I wanted to apply this framework to Books of Hours, which are perfect for this kind of interpretation. People in the Middle Ages and Renaissance loved their Books of Hours, and you can see that in how they personalized and handled them. Kathryn Rudy has written extensively about this, showing how people left physical marks—kissing, touching, and so on.

Visualizing Structure and Variation

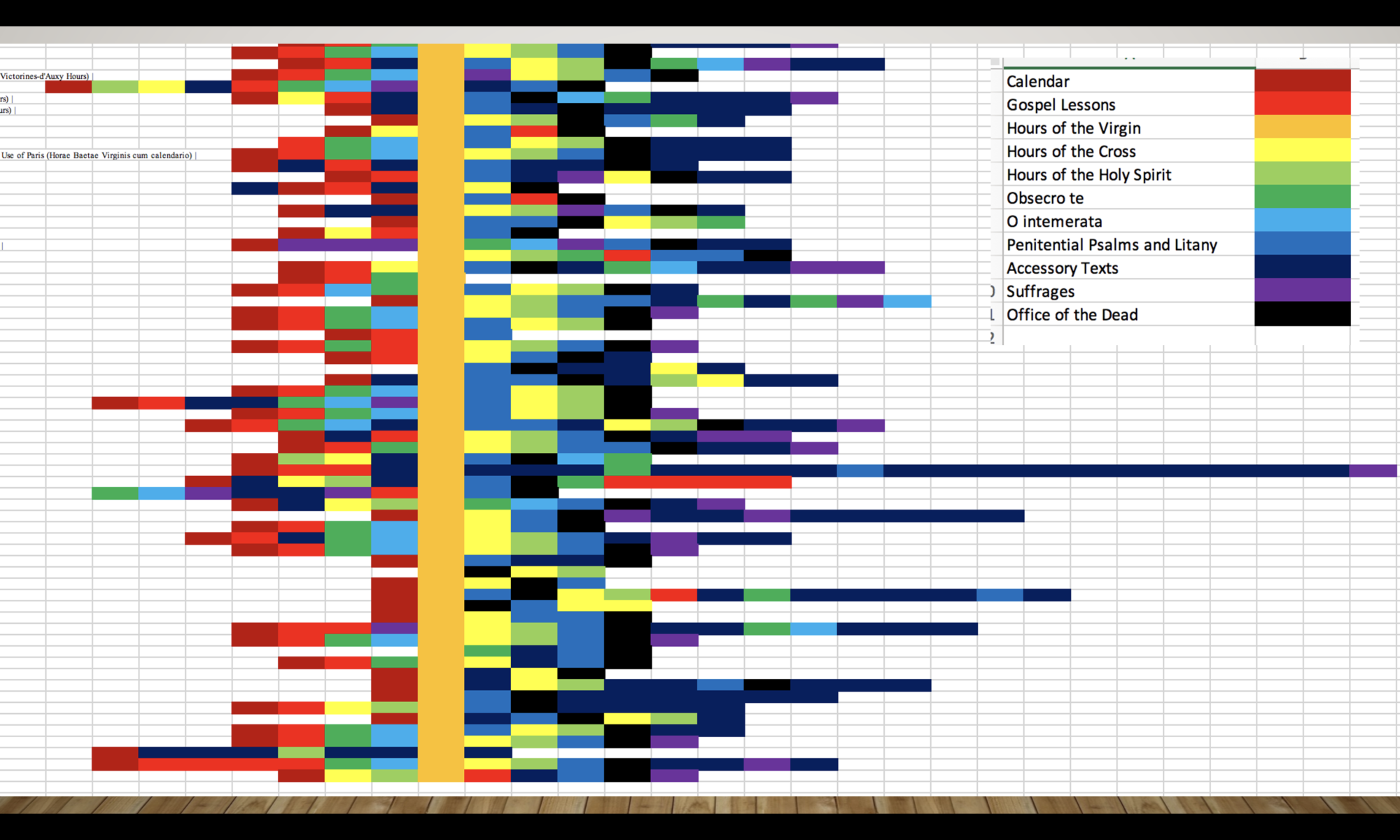

So what was I doing? I was looking at variations in the texts across many Books of Hours, mostly from collections in Philadelphia and the Walters Art Museum.

Here, each manuscript is laid out according to its structure. The Hours of the Virgin—which is typically the central text—is in gold. You can see what comes before and after it in each manuscript. In another version of the visualization, all the manuscripts are scaled to the same length, allowing us to compare how long or short each one is. You can immediately tell which manuscripts have more content and which are more minimal.

Building My Own Book of Hours

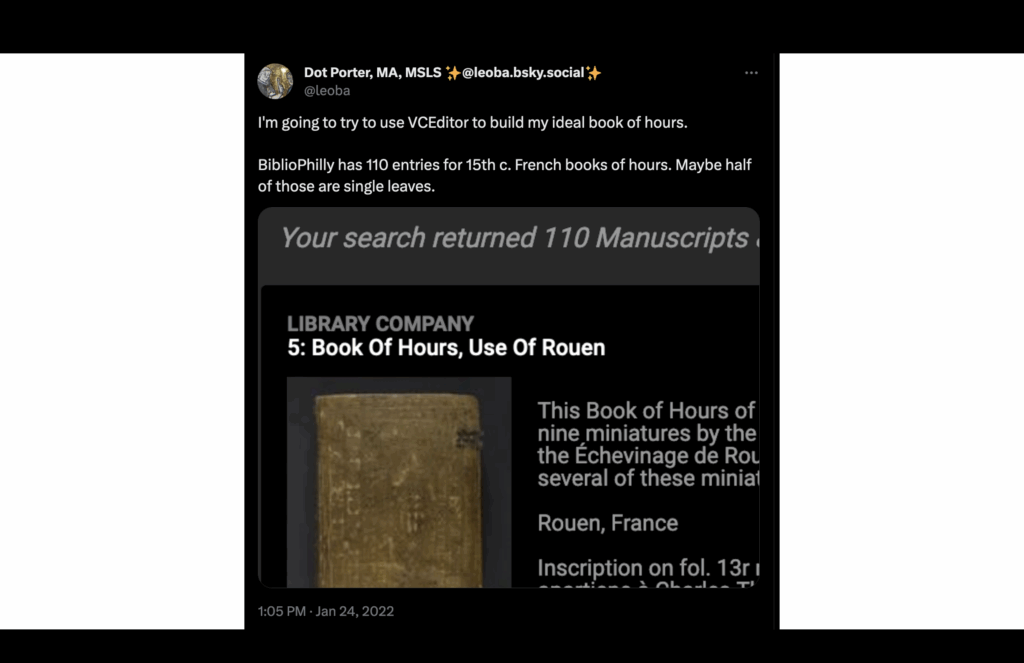

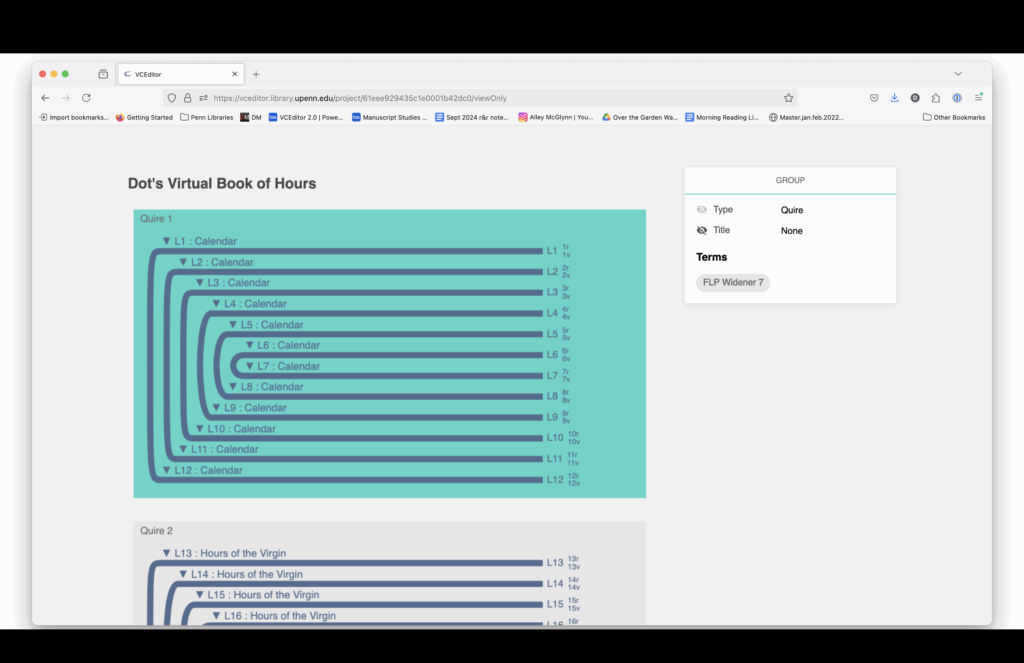

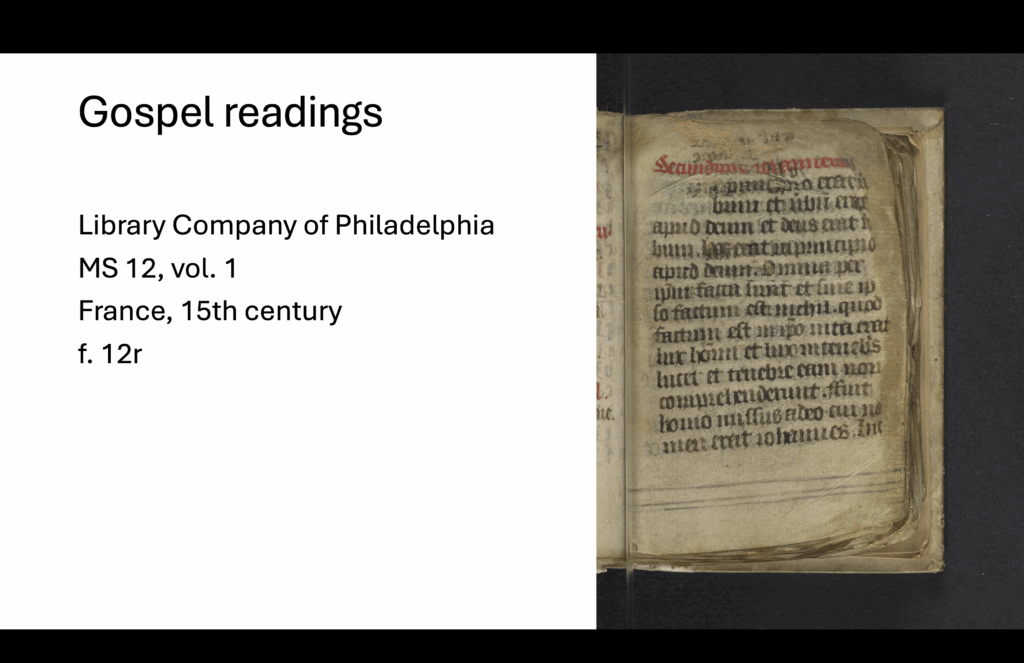

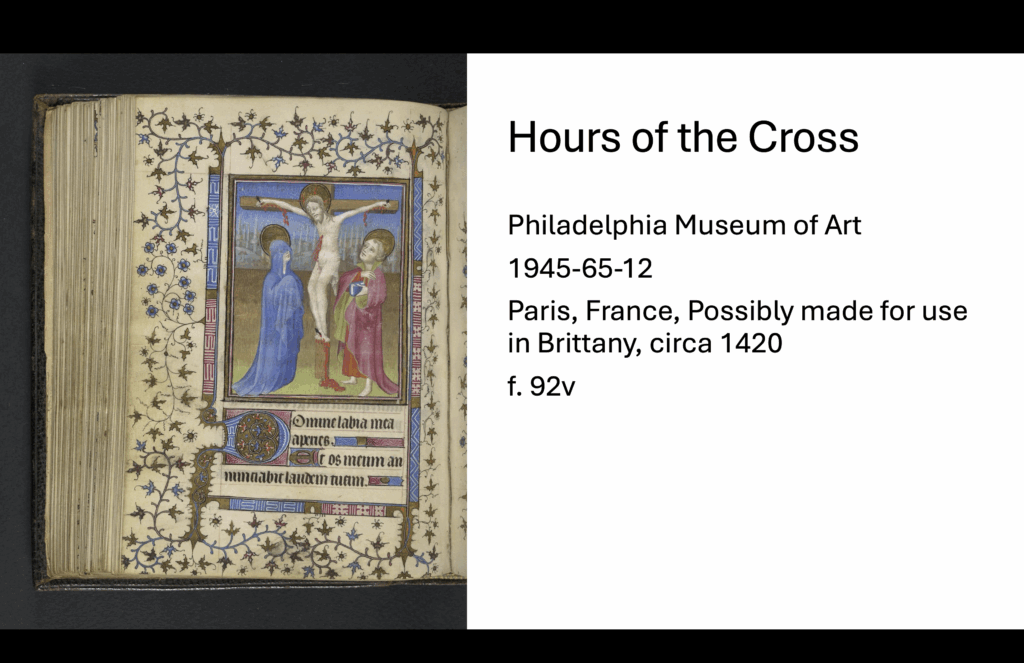

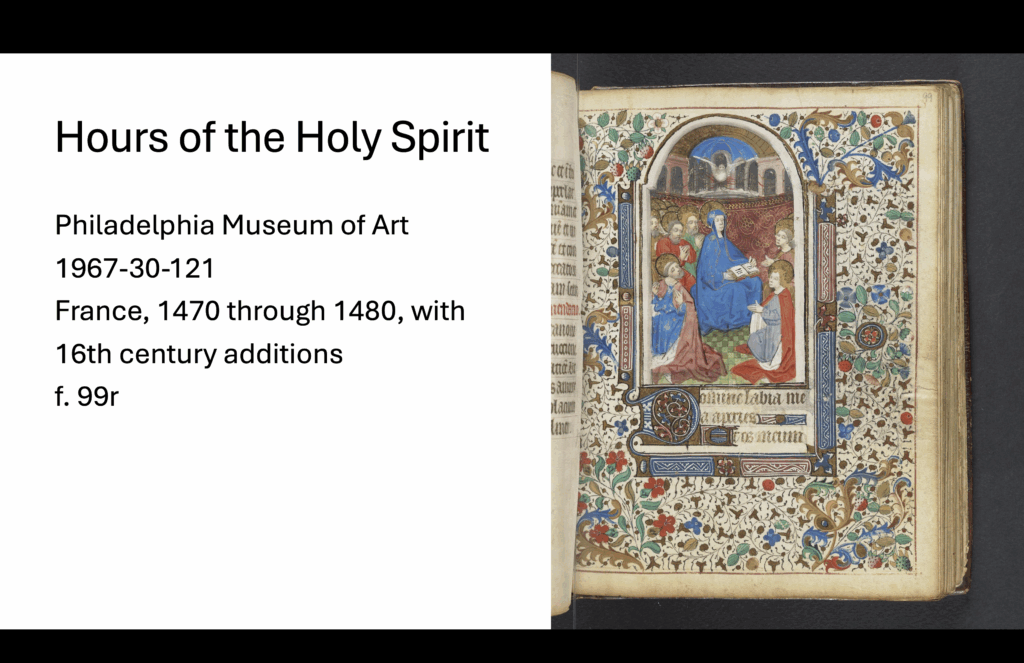

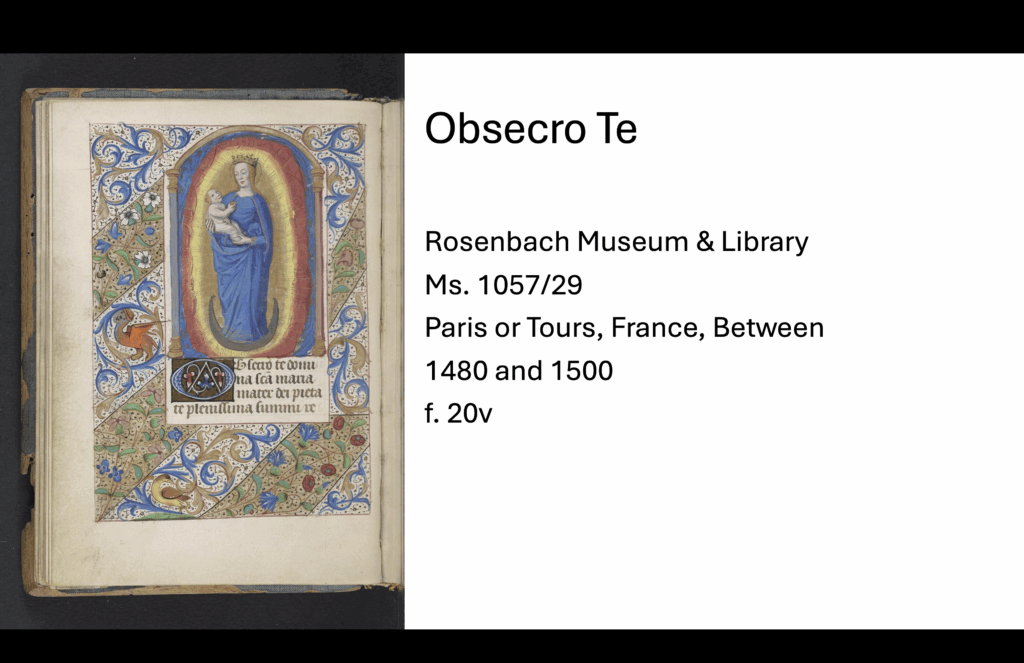

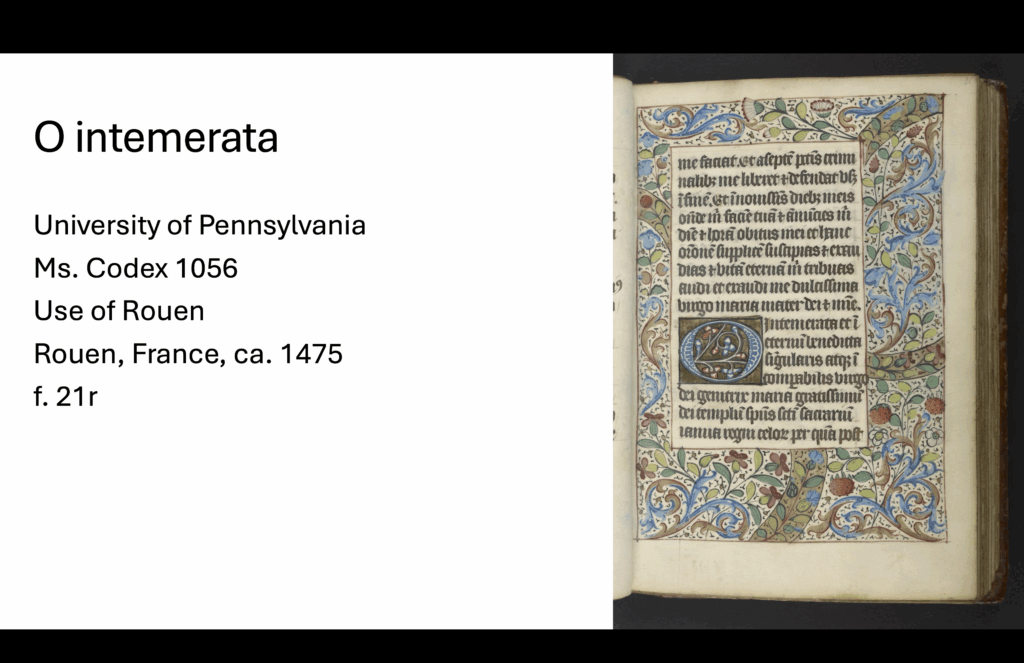

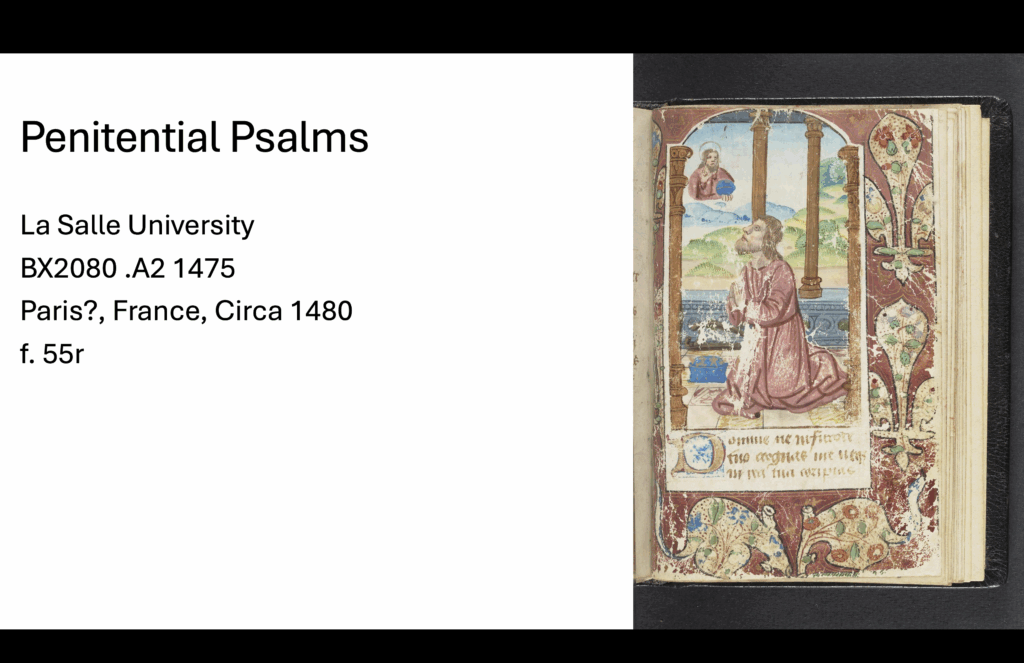

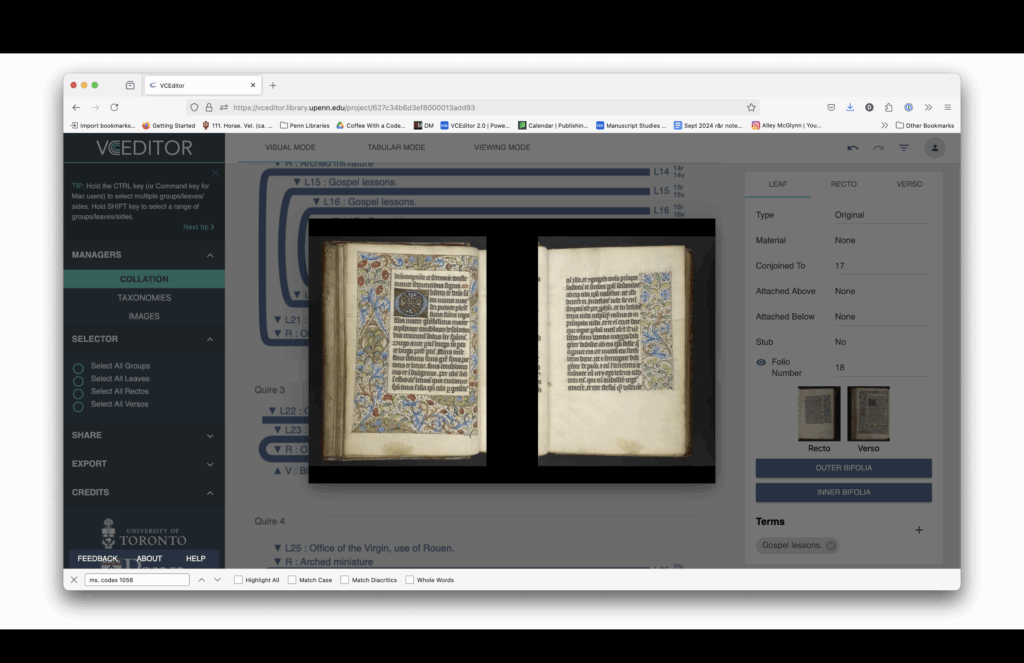

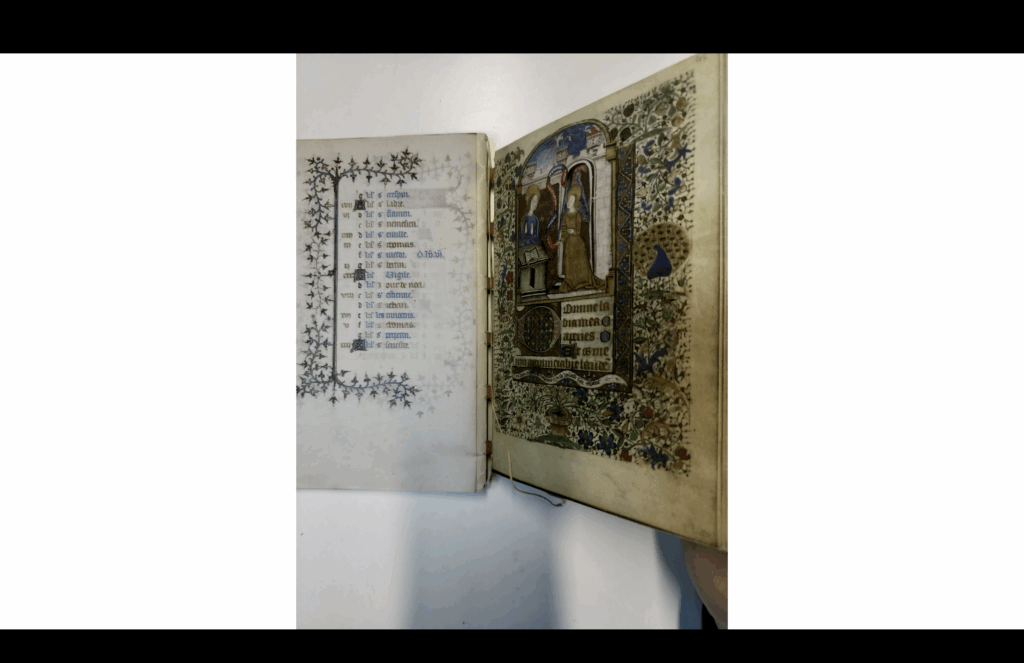

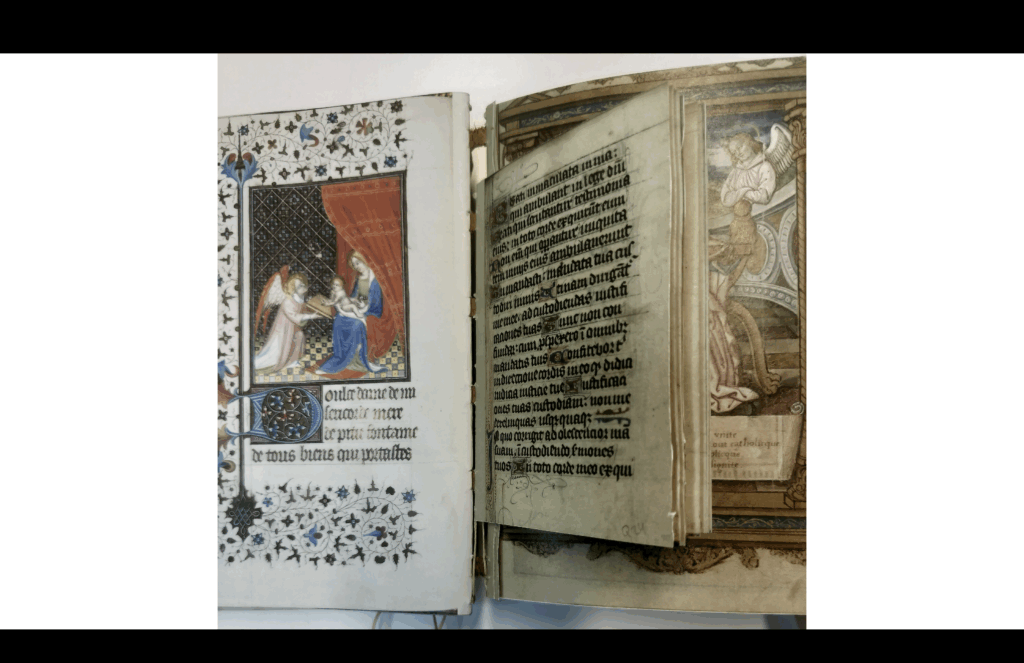

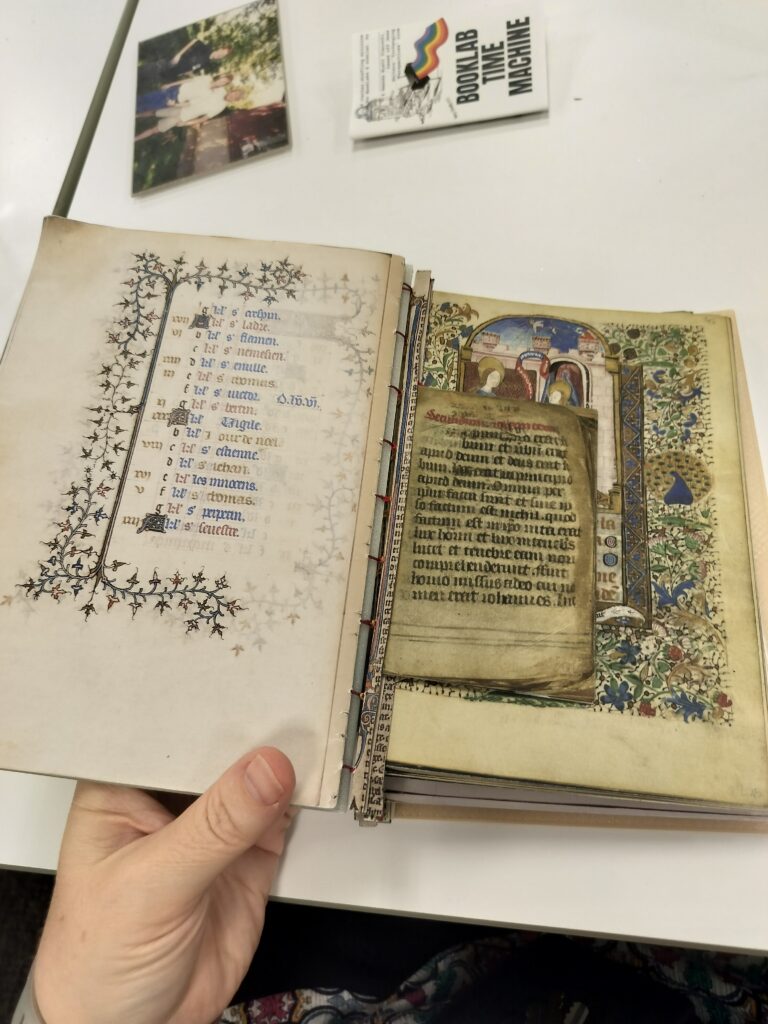

On January 24, 2022, I decided it would be fun to make my own Book of Hours using VCEditor, the structural modeling software that uses the VisColl Data Model. I used digitized pages from the BiblioPhilly project and assembled a new manuscript by virtually “cutting” and combining pieces from different books.

Imagine I have a table full of Books of Hours. I open one up, take the calendar section, and place it aside. Then I open another, take the Hours of the Virgin, and so on—compiling my own version, but doing it digitally.

To guide the structure, I turned to Roger Wieck’s list of standard contents and orderings for Books of Hours in Painted Prayers.

Although Books of Hours as Transformative Works challenged the idea of a fixed order, for this exercise I followed Wieck’s list. You can view the model at tinyurl.com/b-of-h.

The structural diagram links to digitized images. You can see how each section is drawn from different source manuscripts, mostly 15th-century and mostly Paris Use.

Here is a complete listing of the sections and the manuscript from which each section is drawn.

Elaine Treharne—and many others, including myself and, I think, some people in this room—have talked about what digitization does to a manuscript. Essentially, you’re taking a thing apart virtually. You’re deconstructing it, and then reconstructing it through interfaces.

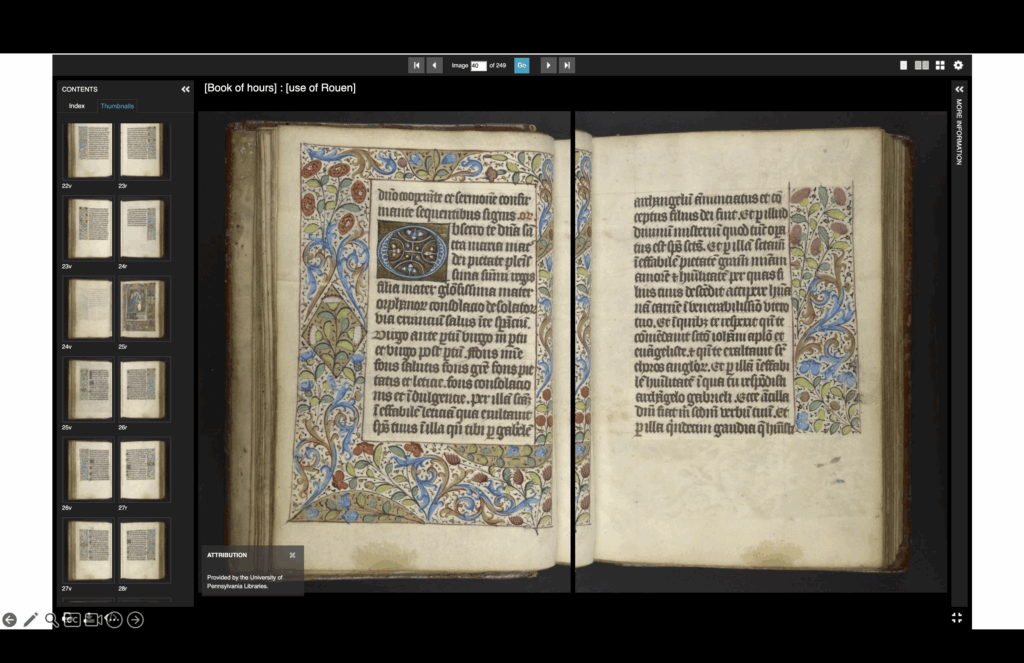

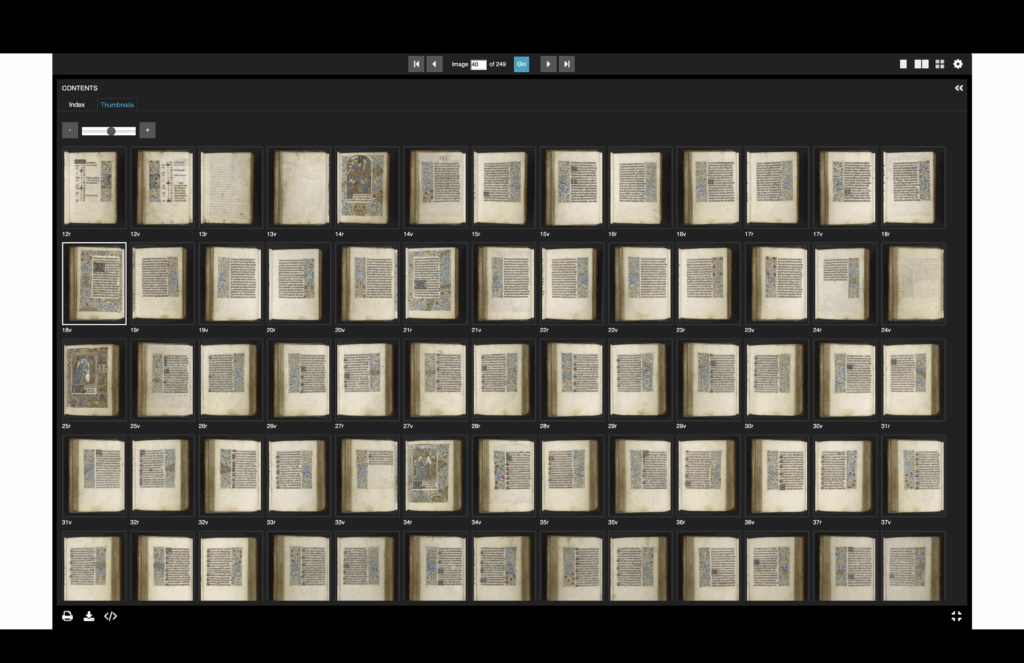

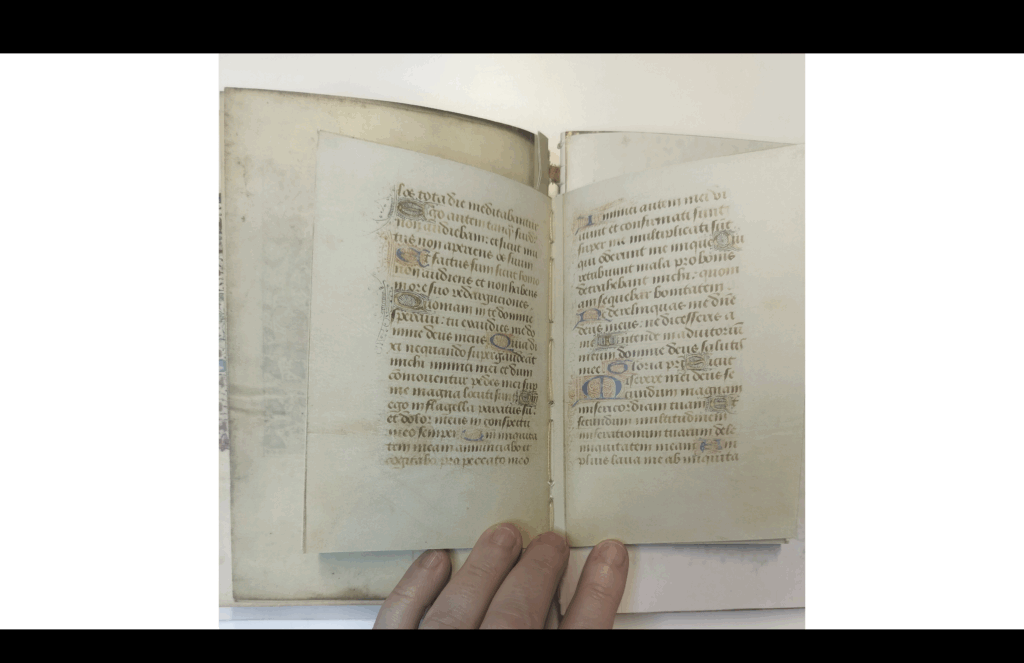

Here’s a very common type of interface—probably the most common: the book reader. It’s designed to imitate the experience of sitting and paging through a book. You see the individual leaves, but you also get this opening. We can tell there’s something artificial going on—there’s this black line in the middle—but it’s obviously just two photos placed side by side.

Then you have things like gallery view, which is another kind of interface—just a different way of interacting with the digital object.

VCEditor itself is yet another interface. Instead of viewing the manuscript as something you read page by page, you’re seeing it as a structural object. For example, when I click this button, it pops up a view—not of a page opening—but of a physical leaf.

This is a bifolium, two leaves physically connected. If you were to take the book apart, you’d get this single sheet, but you’d never see these two pages side by side in the bound book. They don’t face each other in the codex.

And I had this realization just yesterday, during Carrie’s paper in the first Johanna Green Memorial session: what I’m doing is making an interface for a digitized book—or multiple digitized books—but it’s a physical interface, not a digital one.

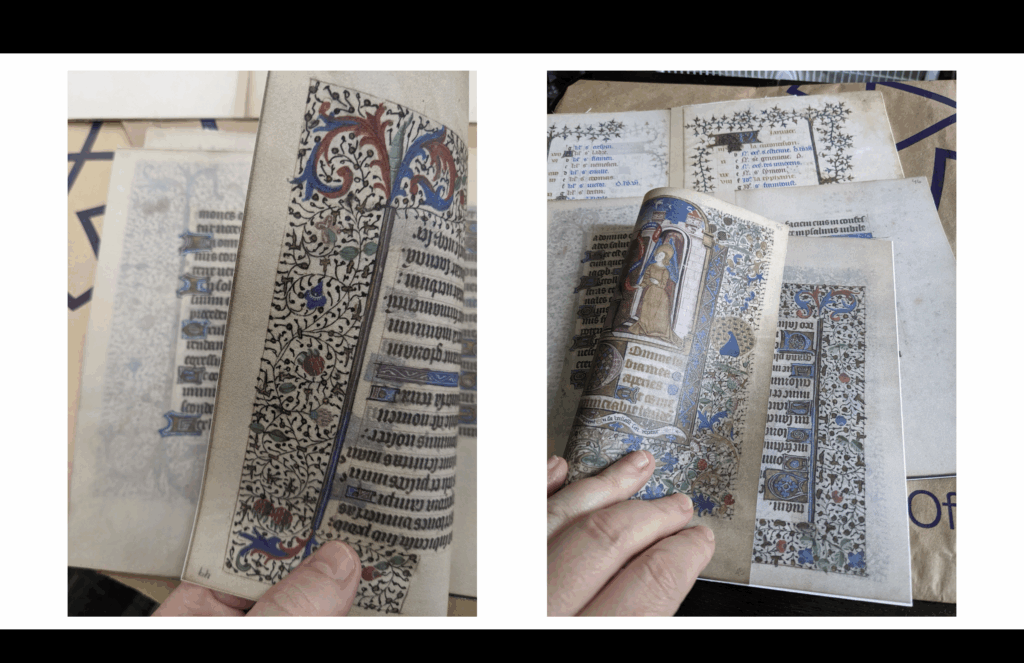

After building this digital structure, I wondered: Could I print it out and bind it as a physical book?

So I did. Eventually.

At first, I made mistakes—like printing the back of the sheets upside down. (Some of these sheets have found their way into the current binding structure in the form of guards.)

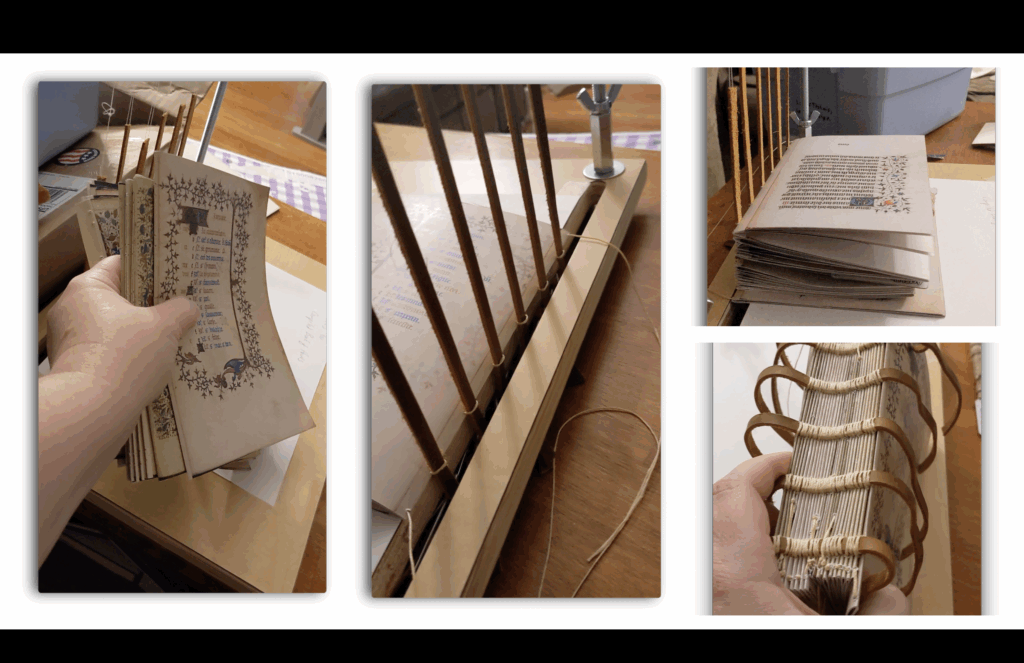

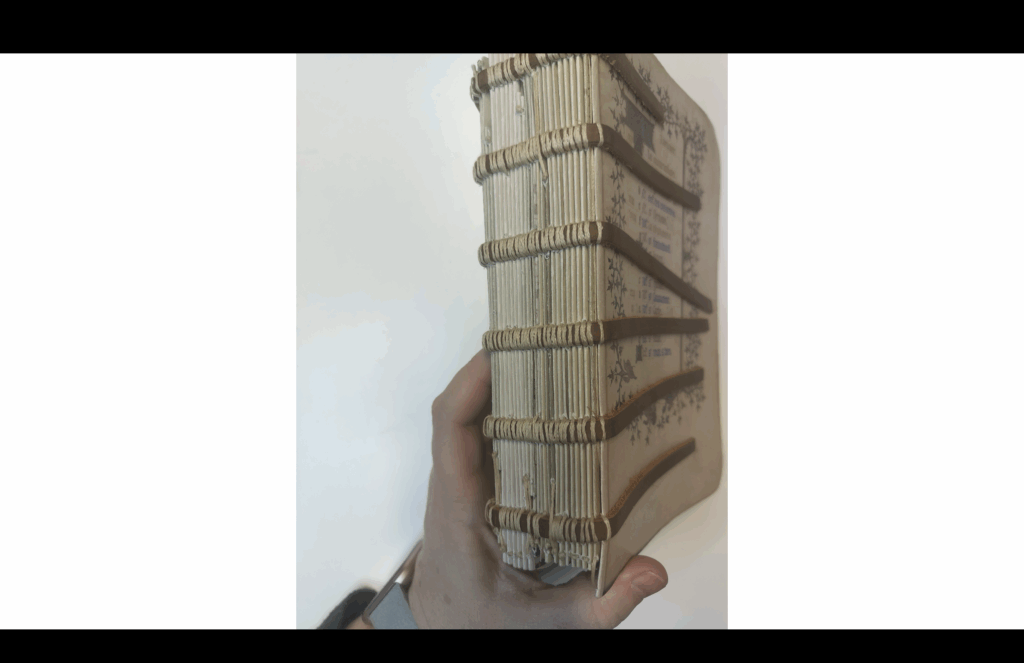

Eventually, I got clean bifolia printed, organized them into quires (based on the structure of the parent manuscripts) and began sewing them onto leather thongs. I had never bound a book before, but I got a sewing frame, learned the basics, and bound the manuscript.

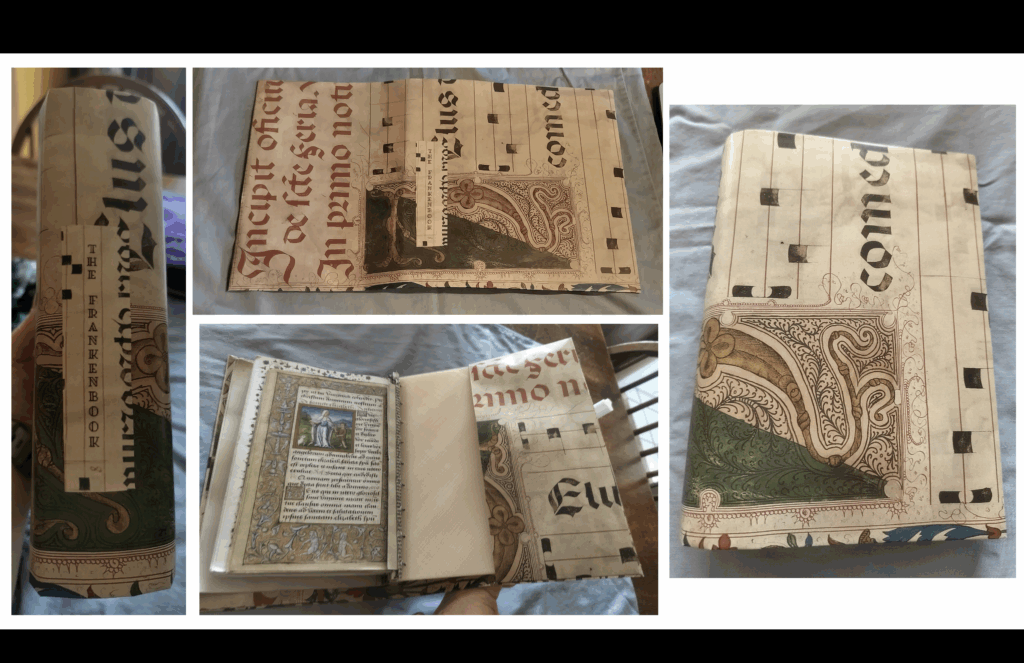

(more photos of the first binding of the Frankenbook)

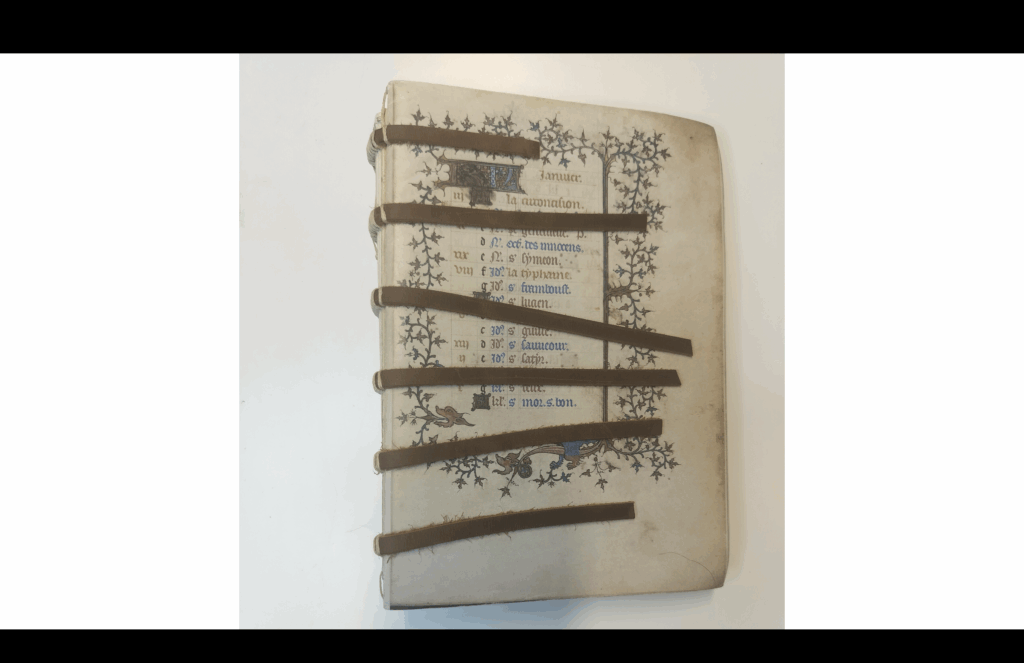

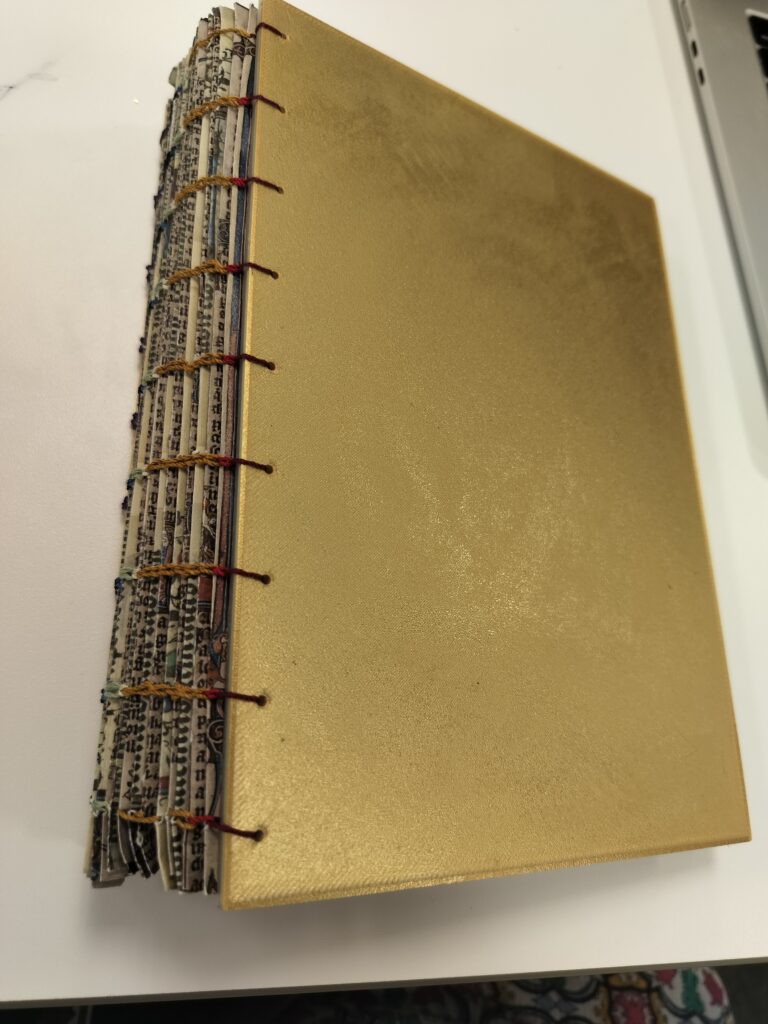

By mid-2022, I had a bound textblock—but I didn’t love it. Something felt off. Then, earlier this year, I had an idea: what if I did a Coptic binding? I’d been resisting it because no historical Book of Hours has a Coptic binding. But then I thought—this is already a weird, hybrid, anachronistic object. Why not?

(The finished version – with a Coptic binding! The boards are 3D-printed, quire guards are from misprinted quires, and the thread is color-coded to the contents using the same colors as the data visualization for Books of Hours as Transformative Works.)

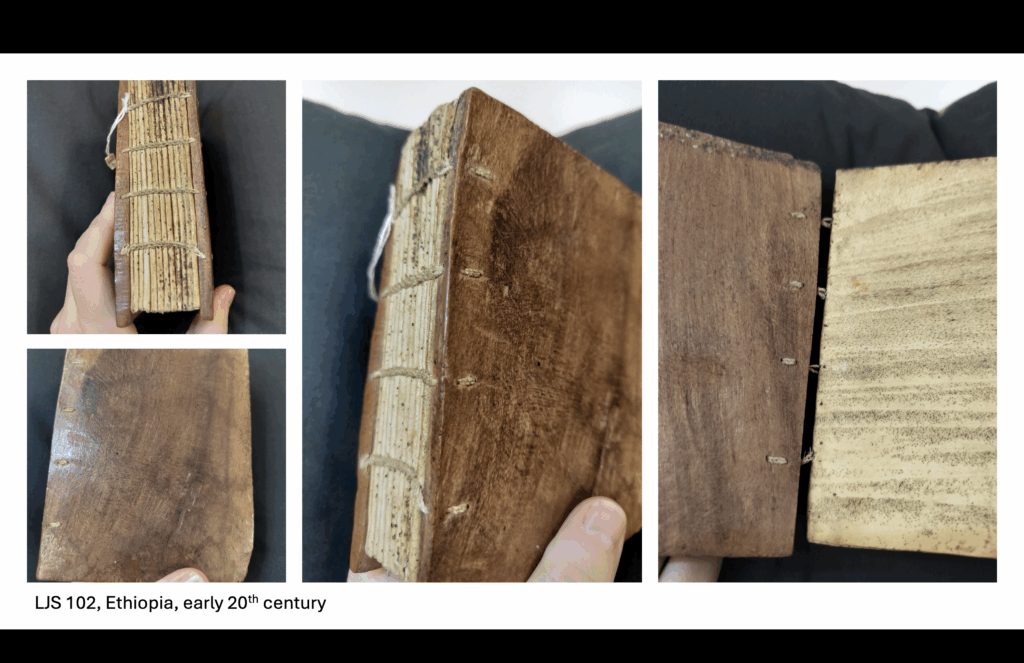

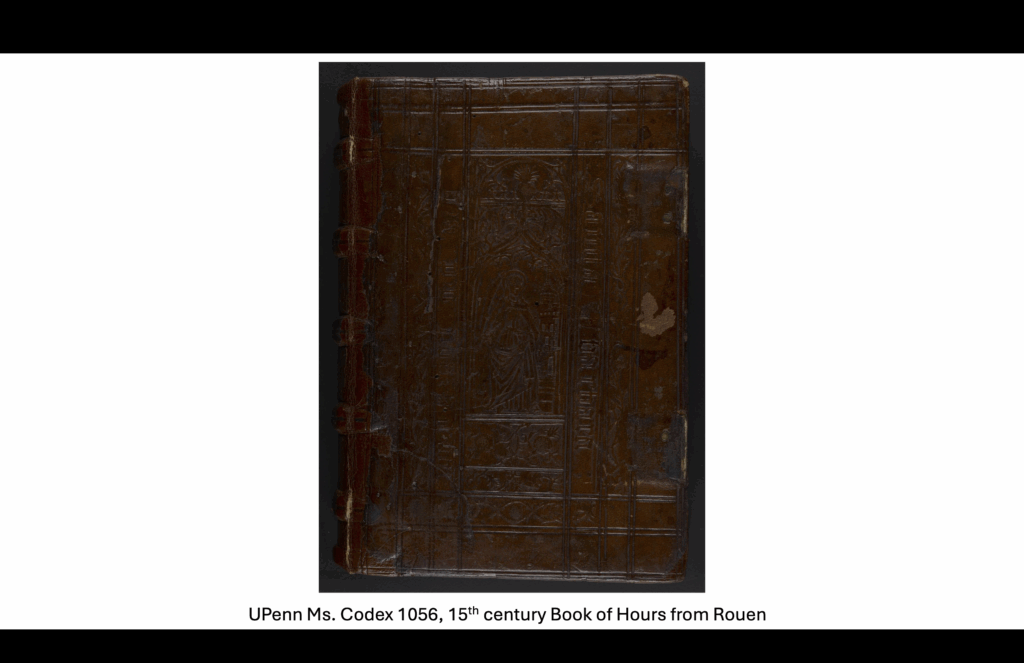

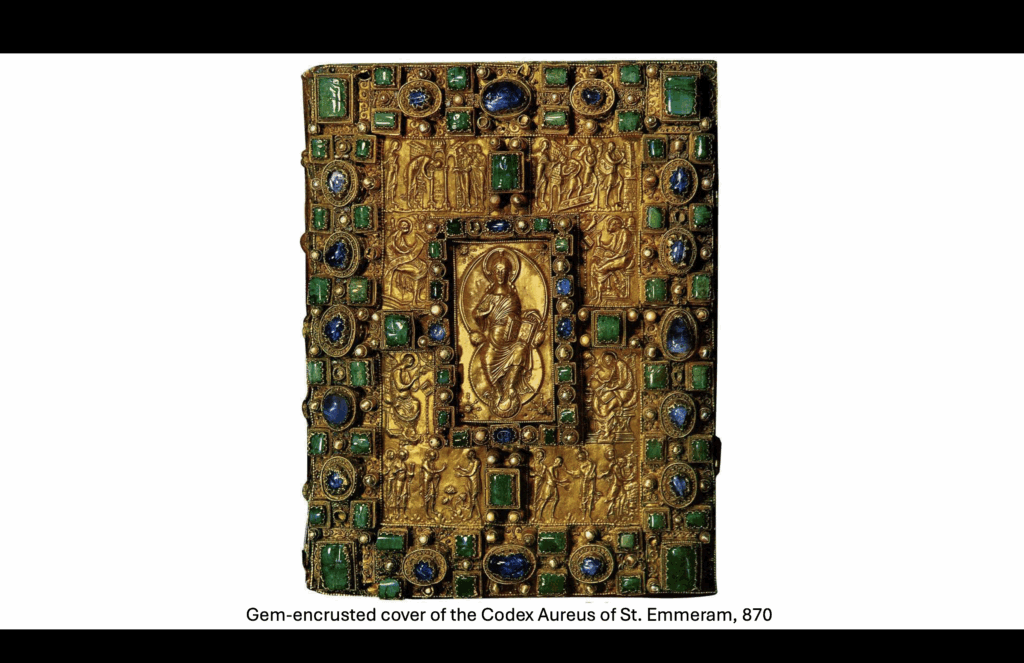

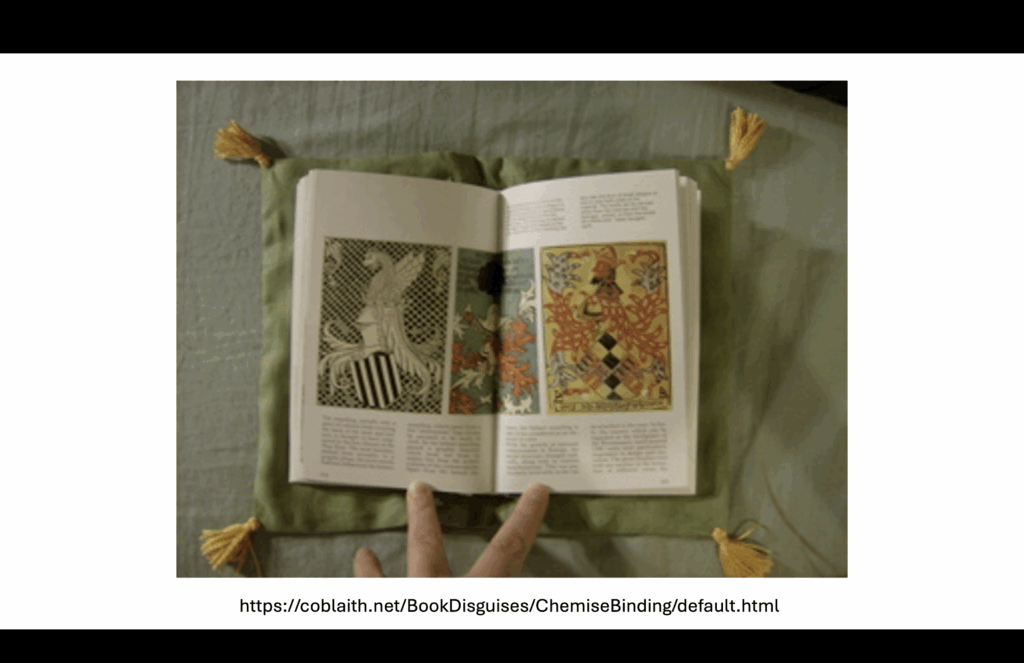

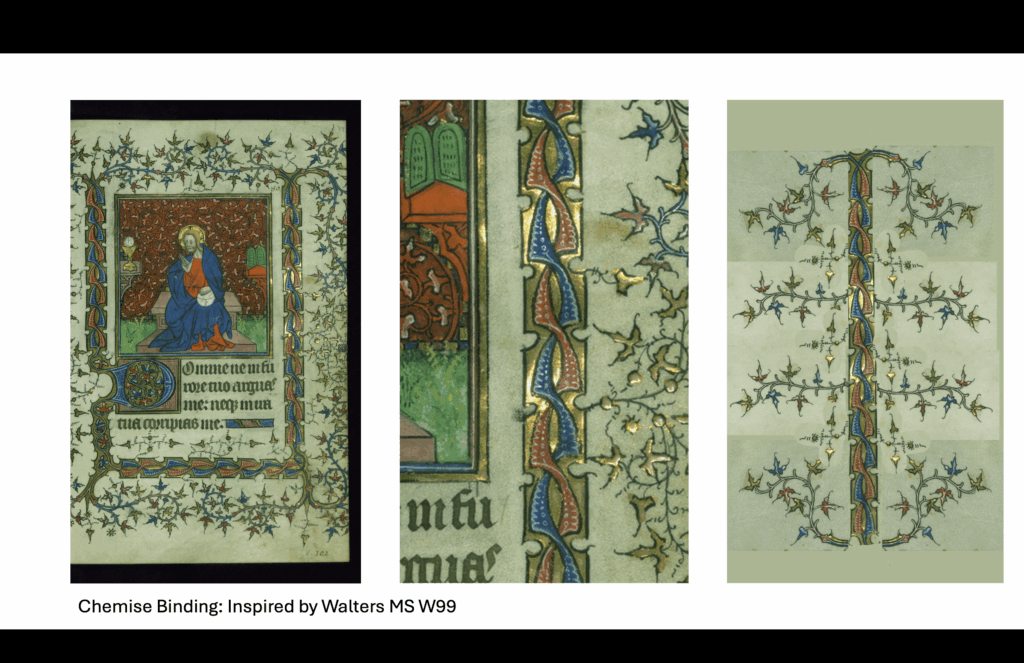

I also started thinking about covers. Should I do something like the leather cover of MS Codex 1056? Or a fancy treasure binding, made of metal with embedded stones? Or a chemise binding, like a 15th-century noblewoman might have carried?

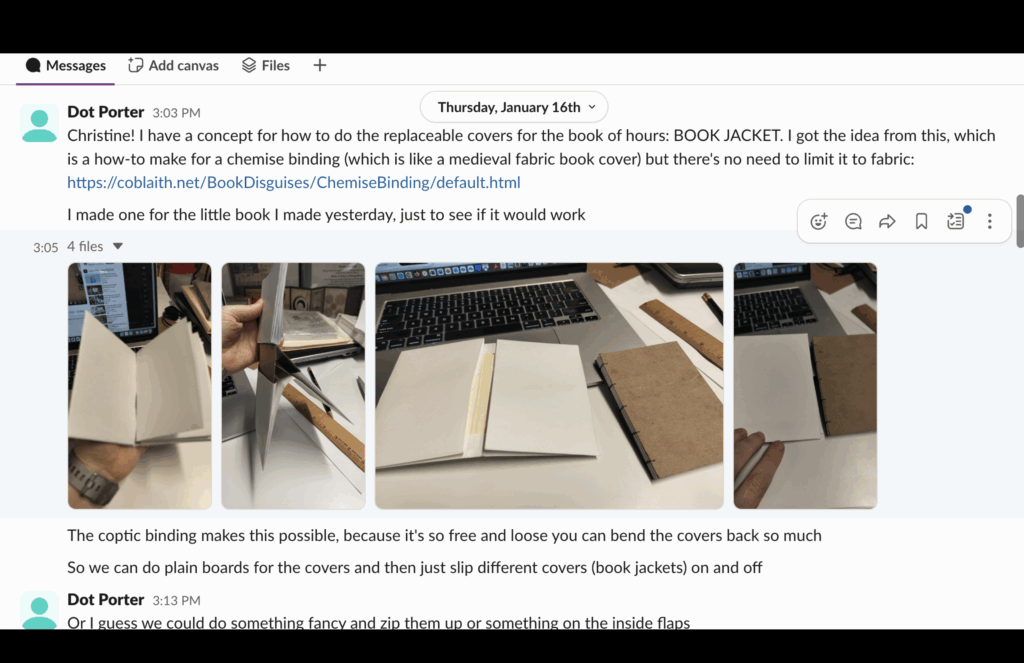

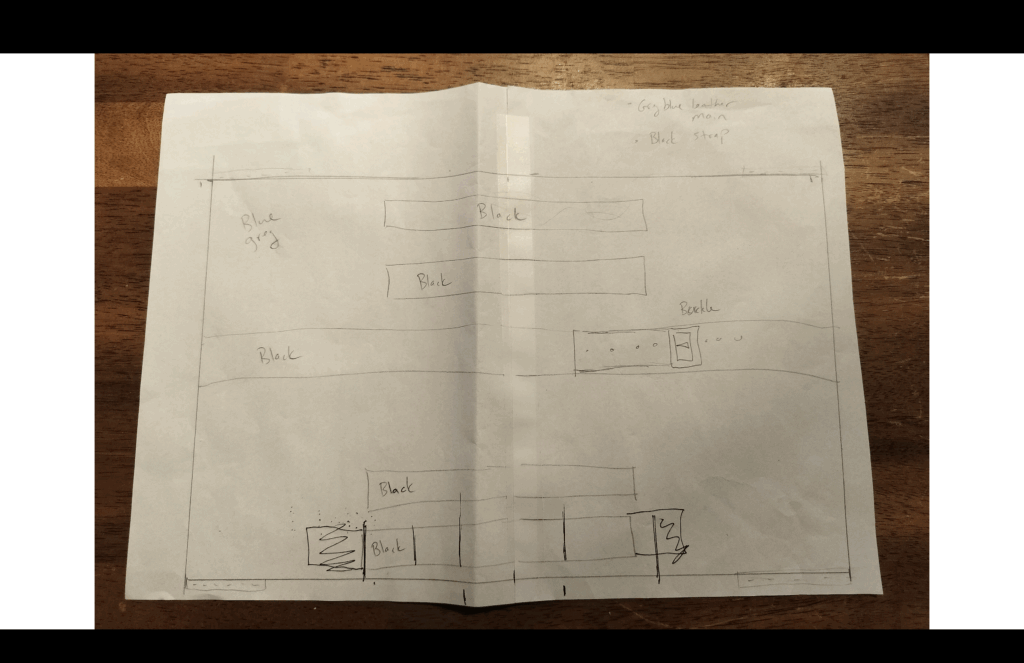

I couldn’t decide. And then, talking to my artist friend Christine Kemp (who works in our makerspace), I had a revelation: why not make interchangeable jackets for the book?

At this point I took a step back and I thought—what am I doing? What I’m making is basically an artist’s book.

I found this blog post from the Smithsonian Unbound Blog to be helpful:

An artist’s book is a medium of artistic expression that uses the form or function of “book” as inspiration. It is the artistic initiative seen in the illustration, choice of materials, creation process, layout and design that makes it an art object. A book that only contains text is simply a book; even if authored by an artist, it would be a book that belongs in a book store or the shelves of a library.

What truly makes an artist’s book is the artist’s intent…

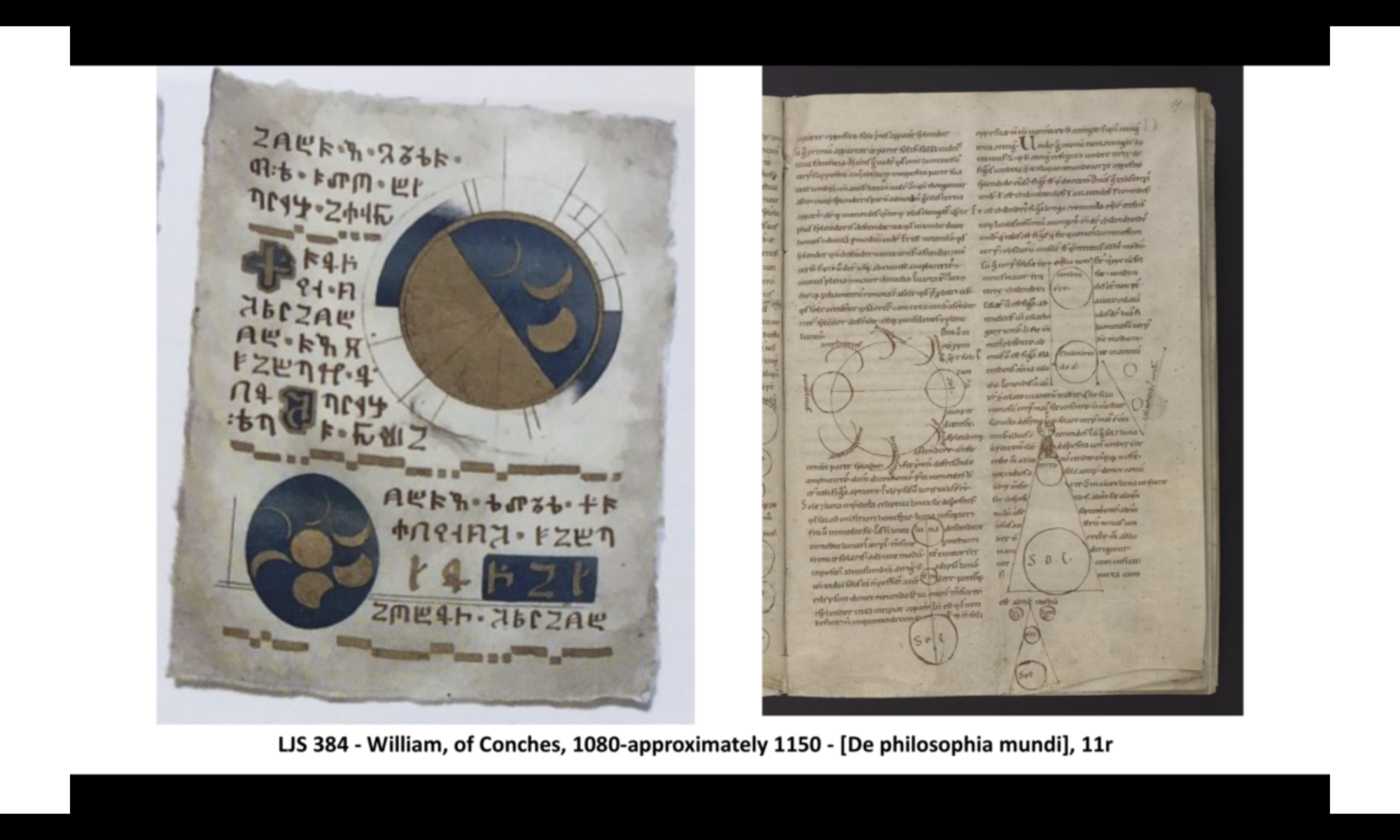

And what is my intent? I want to make something that draws on everything I know about manuscripts. Not just Books of Hours, but all manuscripts.

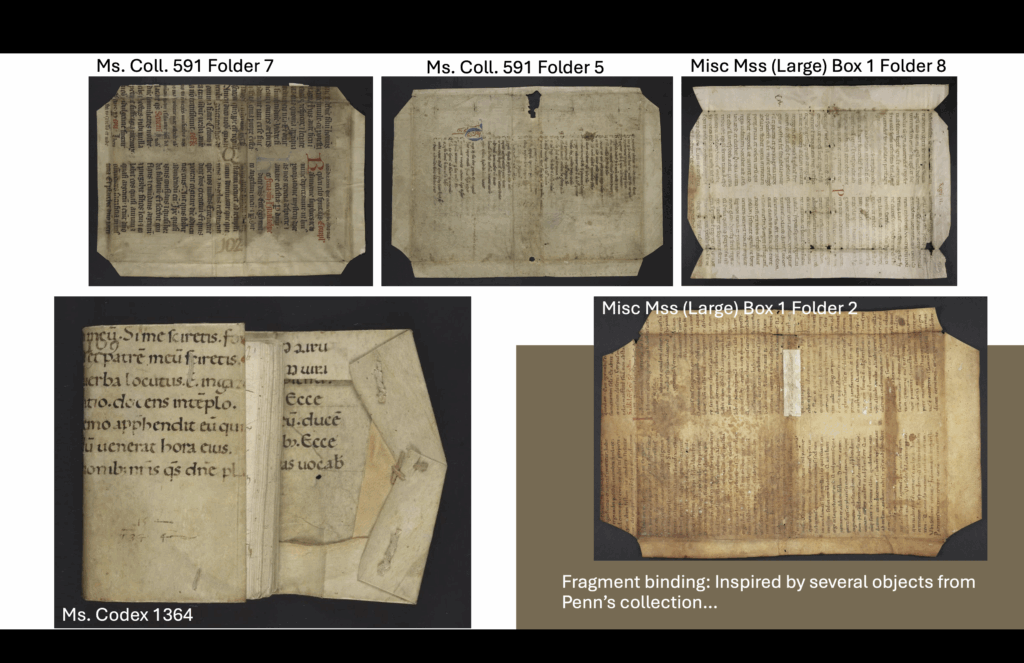

Re-use of manuscripts is something that happened historically. People took books apart and put them back together in new ways. They used fragments to make other things. I’m doing that too—just in a more modern and creative context. So I gave myself permission to explore that.

Part of the inspiration came from #dhmakes, which is a creative digital humanities community. I started engaging more with that group.

Then in May, I went to the Society for Textual Scholarship Conference, where Emily Brooks—who was just hired at Penn and who I’ve been working with—gave a talk “Treasuring Pop Bookishness: Remediating Ornamental Codex Culture in Contemporary Fandoms.” Obviously, that’s right up my alley. She talked about how, historically, book decoration reflected the values and identities of the people who owned them—and how similar practices are alive today in fandoms, where people personalize books by decorating them or adding things, making them their own.

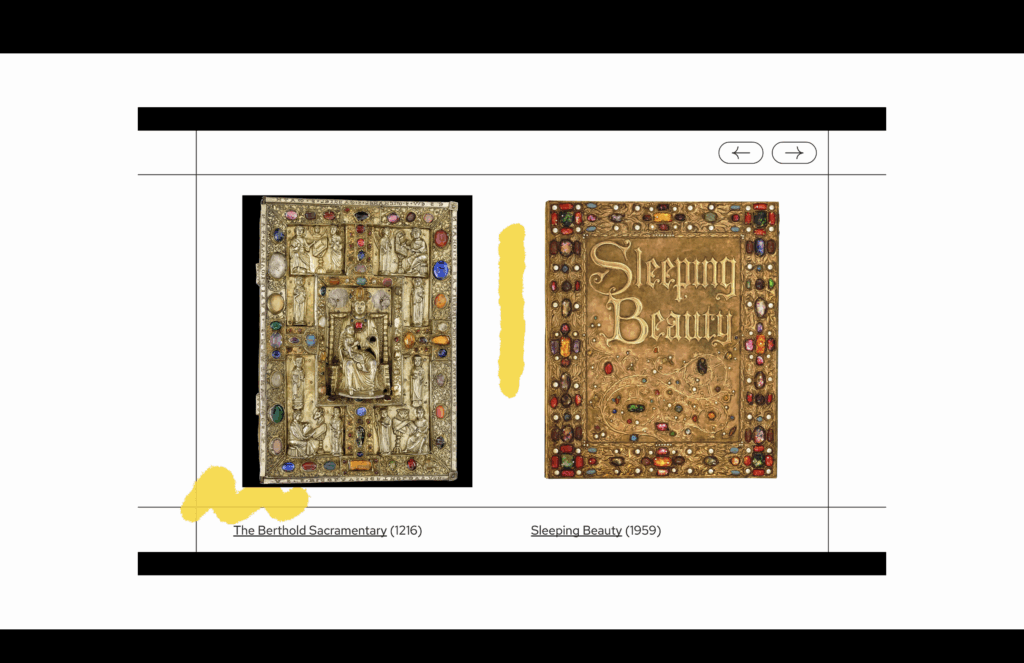

Screenshot from Emily Brook’s talk, showing a historical binding alongside a fan binding.

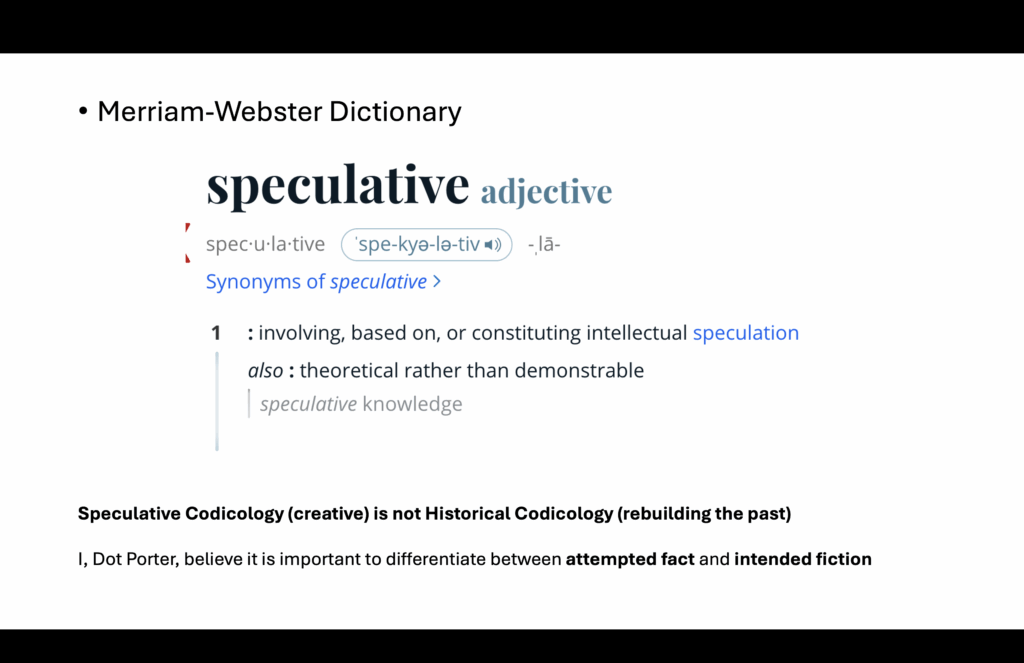

I’ve also been experimenting with what I’m calling speculative codicology. I gave a talk on this in Bloomington, also in May. It’s inspired by speculative fiction—imagining a world that’s just slightly different from ours. It’s explicitly creative. It’s not about reconstructing the past; it’s about doing something new. I think it’s really important to say: I’m not trying to make a manuscript that would have existed in the past—I’m doing something different.

And of course, artist’s books have been another source of inspiration. I have embraced this.

Christine is working with me to create bindings. So far we’ve made a chemise (fabric) binding, and a leather binding, and we will soon start on a treasure binding (with assistance from Emily Brooks, and with stones donated by my son, who has a geology collection).

The first is the chemise binding, made of purple minky fabric, with gold machine-embroidery inspired by Walters MS W99. The inside lining is a dragon from FLP Widener 7, which is the Frankenbook’s Calendar.

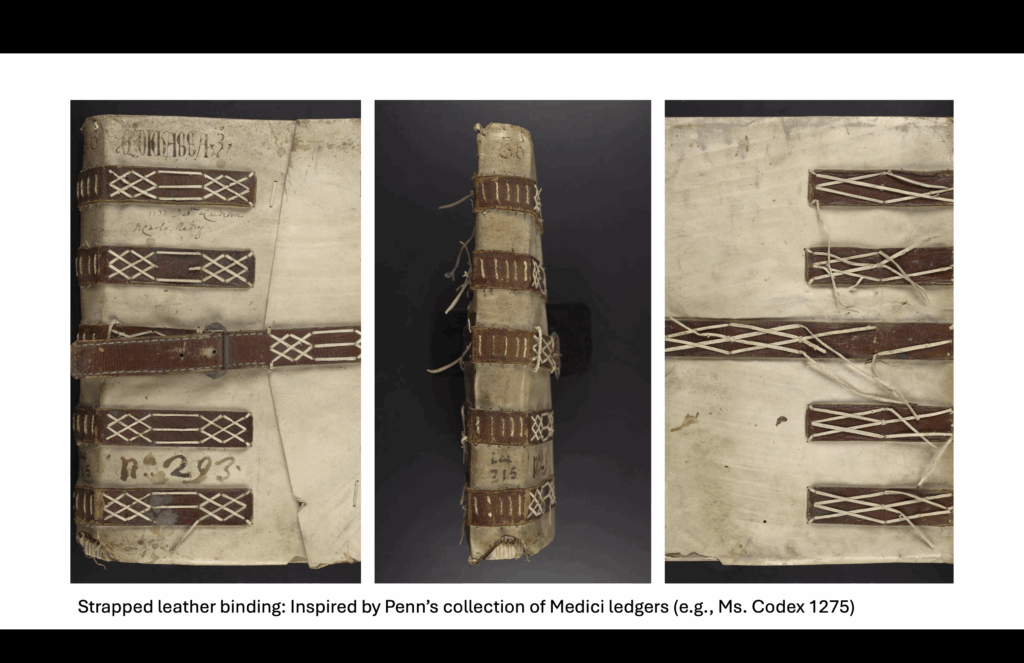

The second is a leather binding, inspired not by any exiting book of hours, but instead by parchment and leather bindings of Medici ledgers, several of which we have in our collection.

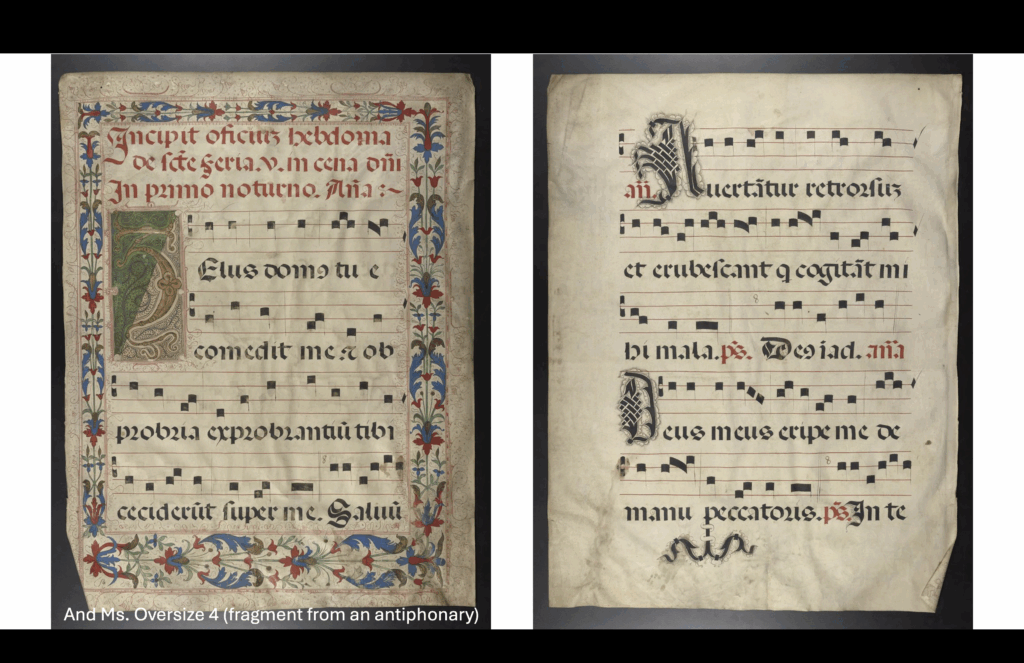

I also made one myself, inspired by fragment reuse. I printed an antiphonary fragment from our collection, at scale, and used it to wrap the Frankenbook.

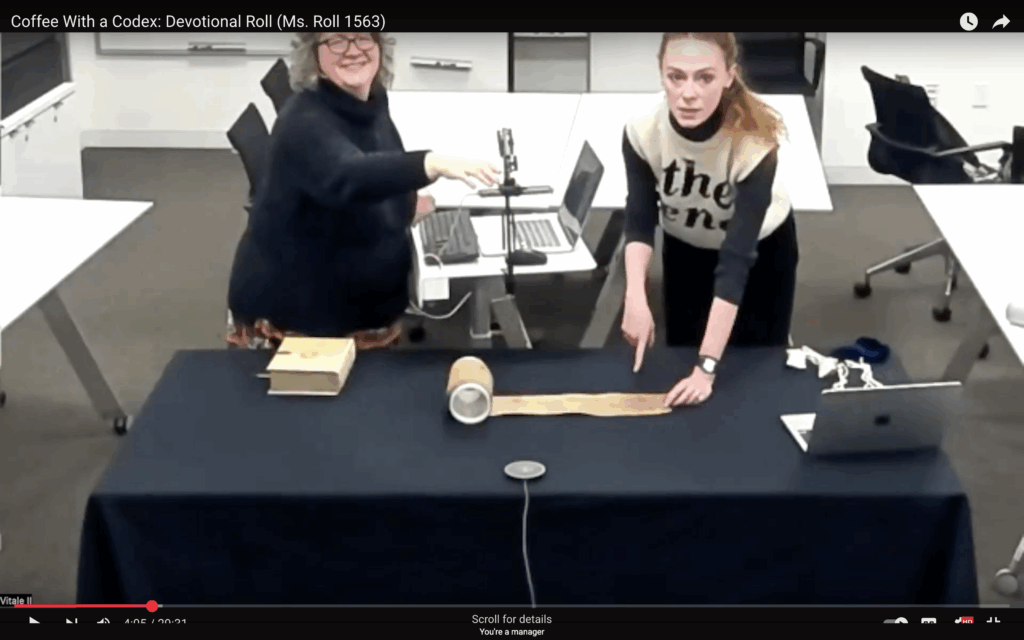

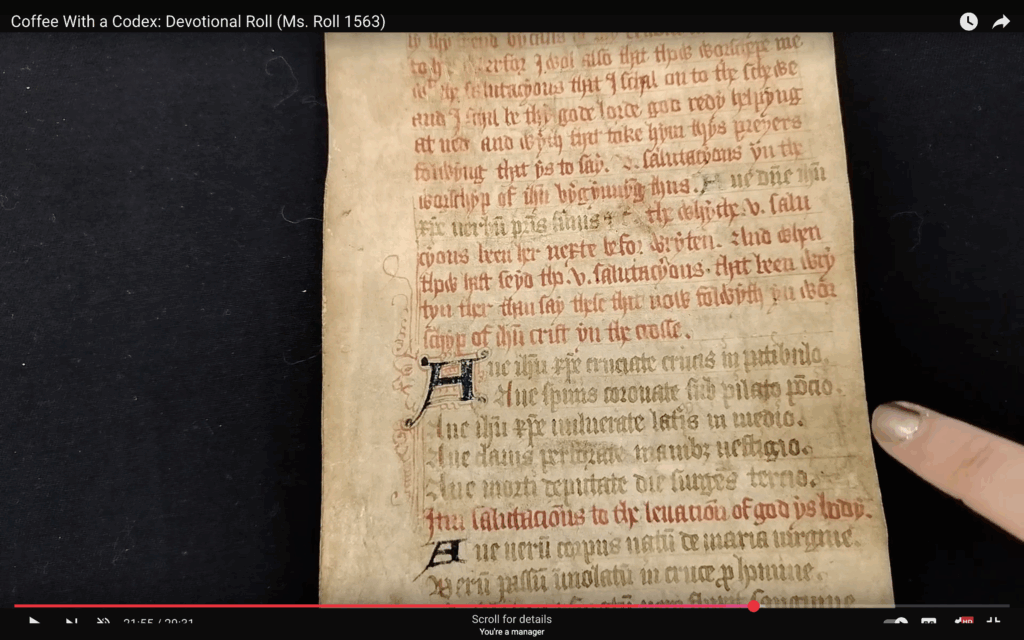

The artist(s) enjoying the fruits of their labor. (Christine Kemp on the left, Dot Porter on the right)

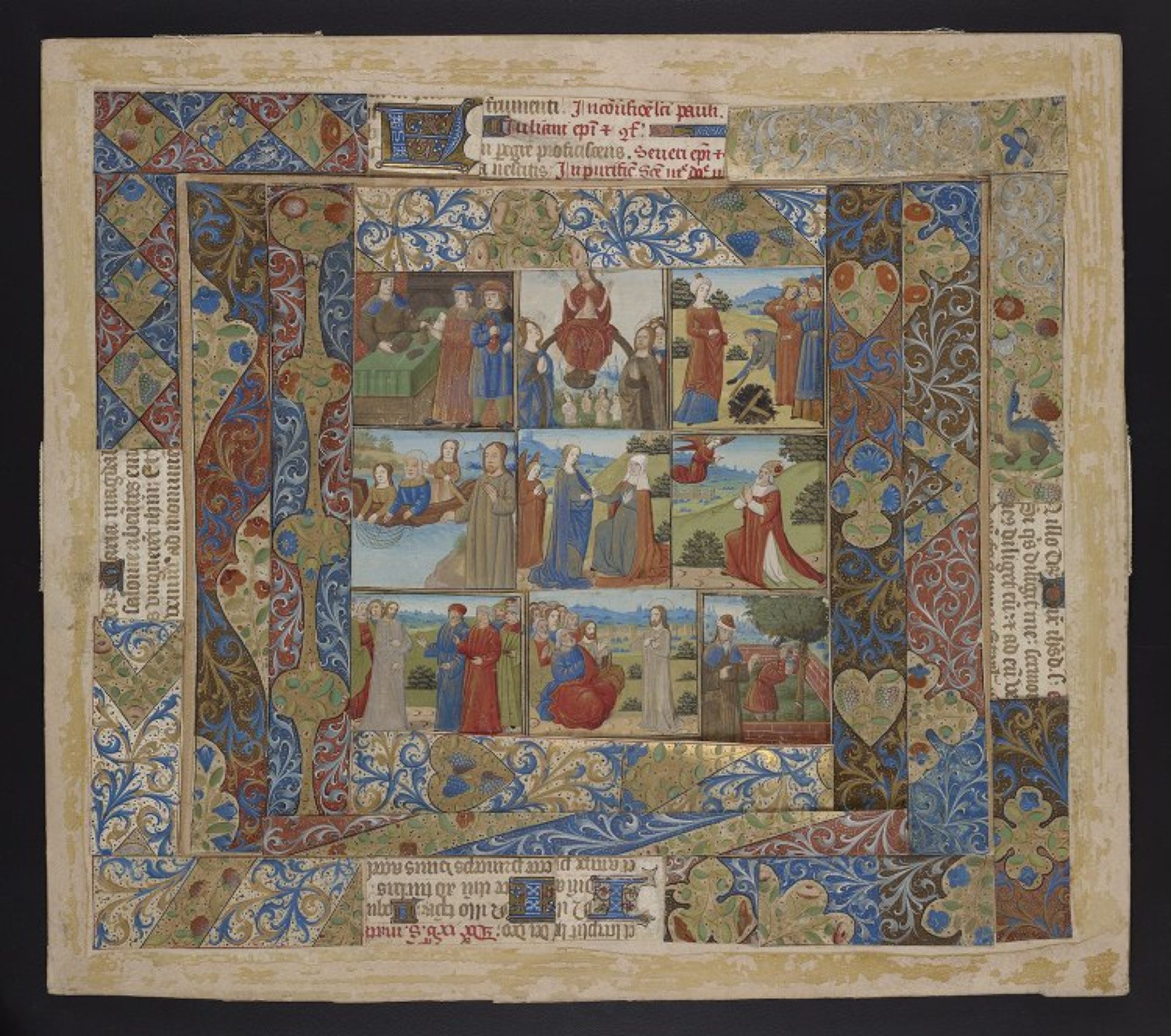

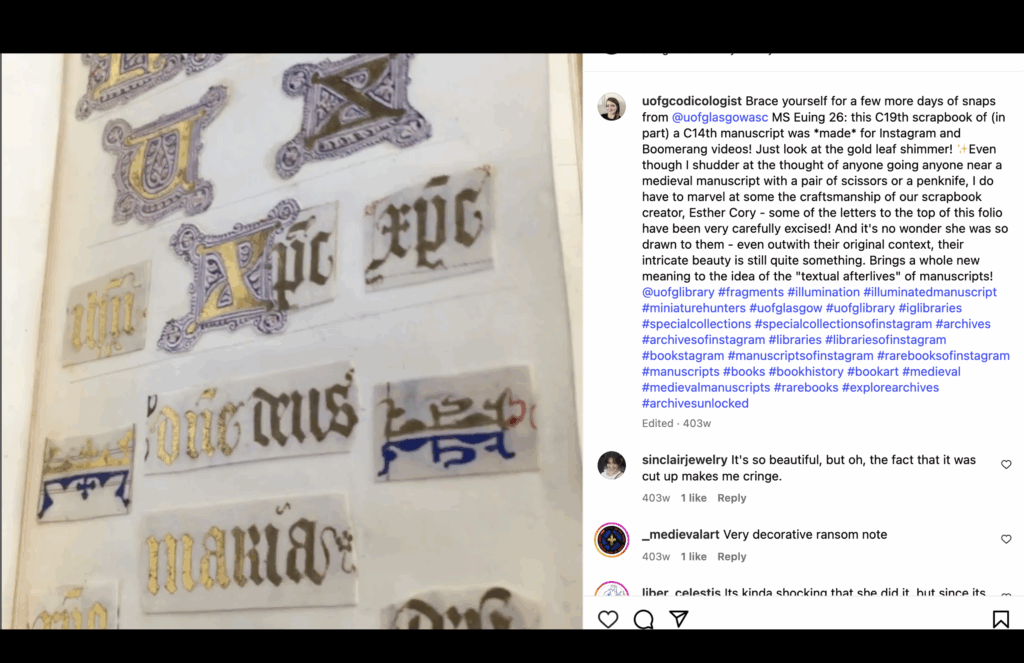

I want to end by returning to Joanna. I think she would’ve loved this project. One of her favorite manuscripts, MS Euing 26, is itself a 19th-century scrapbook—cuttings pasted together from a 15th-century book. Her interest in creativity, reuse, and materiality resonates deeply with what I’ve been exploring here.

Thank you, and I’d love to take your questions or show you the book after the session.